20.02.2023

”Healing the forest, healing the earth, healing the body.”

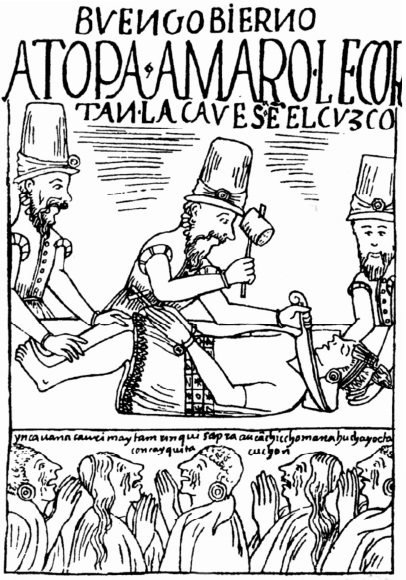

In a collection of essays on images, practices, and discourses of decolonization, Silvia Cusicanqui[1] points out the prolific work of the Kichwa writer and artist Waman Puma de Ayala (1534-1615) for a profound understanding of the events and meanings triggered by the European invasion of the continent of Pindorama, Abya Yala, or America.[2] From 1612-1615, Waman Puma wrote a letter in Spanish more than a thousand pages long, full of Kichwa oral terms and Aymara songs and accompanied by more than three hundred drawings, addressed to the king of Spain and titled Primera Nueva Crónica y Buen Gobierno [The First New Chronicle and Good Government]. In highlighting the originality of the work—which never reached the hands of its addressee and was only rediscovered in 1908—in coining his own ideas to compose an Indigenous theory on the “upside-down world” established by the colonial system, precisely that which he intended to denounce before his sovereign authority, Cusicanqui pays special attention to the author’s pictographic representations of the execution of the last chiefs of the so-called Inca Empire, Atawallpa in 1532 and Tupaq Amaru I in 1571:

Through his drawings, Waman Puma creates a visual theory of the colonial system. In depicting the death of Atawallpa, he draws him being decapitated with a large knife by Spanish officials. The figure is repeated in the case of Tupaq Amaru I, executed in 1571. But only the latter died decapitated, while the Inka Atawallpa was sentenced to death by garrote. Waman Puma’s “mistake” reveals his own interpretation and theorization of these facts: the death of the Inka was, in effect, a beheading of the colonized society. Undoubtedly there is here a notion of “head” that does not imply the usual hierarchy with respect to the rest of the body: the head is the complement of the chuyma—the entrails—and not its thinking direction. Its decapitation then signifies a profound disorganization and imbalance in the body politic of indigenous society. But this somber and premonitory vision, which was expressed in the cycle of 1781, can be contrasted with the image of the Indian Poet and Astrologer, the one who knows how to cultivate food, decipher the marks of time-space and travel through the world, beyond the contingencies of history.[3]

Seeing the intentionality in the artist’s misunderstanding of the manner of Atawallpa’s execution, a fact that was certainly public and notorious at the time, the Ch’ixi sociologist thus sees a gap through which her aesthetic expression gives way to a singular political interpretation. In this way, she extends Puma’s gesture to the affirmation that the aforementioned decapitations refer to an imbalance and disorganization in the entire “political body of indigenous society.”

The decapitation of the Inca chiefs as an indicator of the end of the Indigenous worlds marks, at the same time, the beginning of the establishment of the capitalist system itself—the domination of capital as the reign of another head, the crowning of another logic, that of the People of Merchandise[4]—insofar as the genocide of our ancestral peoples, the dispossession of their territories, and the economic exploitation of the ecologies of this continent as natural resources have constituted some of the conditions of existence of integrated global capitalism. Moreover, a final aspect that stands out in the sociology of the image of these massacres is Cusicanqui’s mention of the execution of the last Sapa Inca by means of the garrote, an instrument of torture developed by the inquisition and used against the enemies of Christianity. From the perspective of another contemporary thinker, Patricio Guzmán, through his trilogy of documentaries on Chilean memory (2010-2019), all this habitus of indifferent genocidal violence, during centuries of colonial history directed at native peoples from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, resurfaces in the Chilean military dictatorship, this time targeting civil society and popular power.

In countless ways, the contemporaneity of Ouramerica finds itself grappling with issues that have been imposed on it by the reproduction of coloniality among us. It is complex and even misleading to immediately recognize borders and periodizations when these have been so arbitrarily decreed, according to logics alien to Indigenous ways, with arbitrariness and silencing prevailing most of the time. In line with Indigenous perspectives, anthropological and archaeological studies are currently revisiting basic notions about the idea of humanity underpinned by the hegemony of Western thought and institutions. With destructive effect, the Western idea of “humanity” functioned as a kind of persistent myth, responsible for instituting a line of exclusion beyond which thousands of native peoples around the world saw their landscapes devastated and were cast into the trash can of history through enslavement or genocide—peoples whose ways of life and social organizations, it should be noted, have never depended on the systemic exploitation of other peoples, but are and have always been sustained through their own cosmopolitics, an ecology of knowledge that involves non-human beings, environments, and entities integrated into their own ways of conceiving the earth and the cosmos.[5]

When thinking about Brazil’s Indigenous territories today, it is inevitable to immerse oneself in the parabolic narratives of Ailton Krenak. A young activist who was at the forefront of the defense of the rights of the country’s Indigenous peoples in the 1980s—a time when an entire generation flourished, responsible for embodying the emergence of an Indigenous social movement fighting for rights—he was responsible for a famous ceremonial and political speech, of struggle and mourning, at the National Constituent Assembly of 1987-1988, playing a key role in the inscription of these original rights in the country’s constitution.

In contact with like-minded cultures of Indigenous peoples around the world, as well as in tune with the world of politics and the arts, in recent years his speeches and oral narratives have been transformed into books of great success, being translated into several foreign languages. Among rivers of ideas and memories, in Ideias para adiar o fim do mundo [Ideas to Postpone the End of the World] (2019), he weaves the following commentary on the identity of his people:

The name Krenak is formed by two words: kre, which means “head,” and nak, which means “land.” Krenak is the legacy of our forebears, the memory of our origins, which we identify as our “headland,” as a humanity that cannot understand itself without this connection, this deep-set communion with the earth.[6]

In orienting horizons of struggle and healing, Ailton’s explanation of his Krenak people’s ethnonym finds powerful resonance with the orientation of his own life ethic, as well as with the colonial theme of decapitation and its necropolitical variants. Head of the land: it is like a form of ancestral response to coloniality. For religions of African origin, even more explicitly than for Indigenous peoples, the importance of fazer a cabeça[7] (initiation) is a fundamental ritual component of the construction of the person. The ori is the maloca of the orishas (the head of the land). In one way or another, through Indigenous or Afro practices, the connection with the earth, with the elements of nature, and with ancestral entities constitutes a set of fundamental practices and beliefs for the integral health of our peoples and communities, which are also the object of religious intolerance, incapable of recognizing other forms of spirituality.

In the twenty-first century, the Indigenous struggle has gained greater visibility because capitalism itself is advancing in its devouring of the last territories where the jungle and its biodiversity throb, eroding the limits of life on the planet itself. In the words of Ailton Krenak: “The result of our divorce from our integrations and interactions with Mother Earth is that she has left us orphans — not just those termed, to a greater or lesser degree, Indigenous peoples, Natives, Amerindians, but everyone.”[8] At the same time that the Indigenous rights agenda is mobilizing to gain space in chambers and assemblies, contemporary Indigenous art is flourishing in other territories of existence. A theoretical formulation and aesthetic experimentation designed by the acclaimed artist and writer Jaider Esbell, the expression encompasses a varied set of aesthetic manifestations that in the last decade have triggered a revolution in the way of conceiving the native peoples of Brazil, due to the character of authorship and self-representation that these works imply.

Best known for his ability to enchant his viewers with pluriverses of mirações [Spiritual Visions] through his loving virtuosity, Esbell was an activist and thinker of the Macushi people, who took a broad view of the political issues facing Indigenous peoples in contemporary times. In Txaísmo, the first painting in the exhibition Moquém_Surarî: arte indígena contemporáneo [Moquém_Surarî: Contemporary Indigenous Art], curated by Esbell at the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo, part of the 34th São Paulo Biennial, we are confronted with a manifesto in which illness and healing, life and death, are in tension, in the presence of original entities and pictograms. The title is a key idea that has its origins in the term huni kuin txai, the name for a deal between cuñados,[9] but which became known in the late 1980s outside the Acre region of the Amazon[10] as a result of the spread of the Indigenous movement. In short, this idea can be conceived as a way of establishing alliances between worlds, a pact guided by the conscience of collectivity, by reciprocity, and by one’s own affection. Affective alliances, to spread the importance of the struggle for the forest and its citizens (florestania) against deforestation, mining, diseases, and poisons. Healing the forest, healing the earth, healing the body.

Silvia Cusicanqui, Ch’ixinakax Utxiwa: On Decolonising Practices and Discourses (Cambridge: Polity, 2020).

Pindorama is a Tupi–Guarani expression meaning “fertile land,” just as Abya Yala has been used to name both the territory used and inhabited by the peoples as well as the continent prior to the imposition of the name “America” by Amerigo Vespucci in the sixteenth century.

Cusicanqui, Ch’ixinakax Utxiwa, 32-33. The italics are our editorial choice.

Davi Kopenawa and Bruce Albert, trans. Nicholas Elliott and Alison Dundy, The Falling Sky: Words of a Yamonami Shaman (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013).

Ailton Krenak, trans. Anthony Doyle, Ideas to Postpone the End of the World (Toronto: Anansi International, 2020).. David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (Loncon: Allen Lane, 2021).

Krenak, Ideas, 19.

Fazer a cabeça is an expression from Afro-Brazilian religions that refers to a specific ceremony performed on the head of the “son” or believer of a specific saint or orisha.

Krenak, Ideas, 32.

Compadre, comadre, friends.

Acre region of the Amazon (Brazil, Peru, Bolivia) crossed by the river of the same name, an area of armed conflict over the extraction of gold and rubber since colonial times.

Comments

There are no coments available.