Issue 18: Of Passageways and Portals - Abya Yala Brazil

Reading time: 16 minutes

03.08.2020

In face of the social violence fueled by the pandemic, authors Bruna Kury and Walla Capelobo discuss the subversive work of a number of trans* artists to confront the colonial regimes that continue to marginalize dissident and racialized bodies.

The anti-clip “Ménage al Coiote” is a tribute that Mogli Saura, Tais Lobo, and the Anti-Projecto Anarco Fake created for the legacy of the Coiote Collective. The work presents images of actions of the Coiote Collective recorded between 2012 and 2018, among the scenes of the “pornorecicle” film, which will be released in 2020. The Coiote Collective is/was the most forceful and radical dissident sex initiative in Brazil’s recent history. Its extreme performative actions involved scatology, drilling, BDSM, scarification and brend, monstrous sexual practices, and the use of garbage as an ethical, aesthetic, and eco-political resource. Mogli Saura’s authorial music connects the practices of the collective to the struggle of the Cangaceiro movement[1] that occurred between the 18th and mid 20th centuries. By paraphrasing and playing the music Banditismo Por Uma Questão de Classe, by Chico Science and Nação Zumbi, Mogli relates and updates the marginal and insurrection struggle for justice and equality of the Cangaceiro people to the “daily autonomous struggles” of the Coiote Collective. In addition, the music denounces the hetero-violence in which dissident sex people live and the “banditry” that implies processes of transition”. — Mogli Saura

#black #travestchy #prosperity #virus

A joint endeavor of four authors, this text was written during the quarantine as an exercise in shared speech and questioning. In an earlier version, the authors discussed the pandemic in a free-flowing way, in an exercise that explored the intersections of compulsory oppression that already exist in the world today and how we understand them.[2] The authors then invited artists to present works alongside the text that enter into dialogue with anti-colonialism, time, and Sudaka,[3] dissident, and gender-disobedient resistance.

We have been living through a great struggle against a new global pandemic. COVID-19—coronavirus—demands that we be careful; careful what we touch, careful where we go. It has entrenched even more deeply the power of a hegemony in ruins; it is a war of control that in places like Brazil is currently conditioning the recognition of lives in such a way that some people end up underreported, and never become a number or a statistic. The massacre that colonialism brought with it persists into the present and finds its most recent expression in the abuses of neoliberalism. A few years ago, I recall seeing someone who, before grabbing onto a handrail in the metro, cleaned the surface with sanitizing gel. I was shocked. This behavior seemed to me to be racist, since it was a white person who was looking contemptuously around at the other people in the metro car. Of course, it is clear that we must take care of ourselves and follow the rules of the quarantine as strictly as we can, that we must use sanitizer, wash our hands, and maintain general hygiene for our mutual protection. However, we must also be on our guard: we are overrun with words, gestures, and other forms of representation that collude in the dissemination of racism. And in our case—the case of the authors of this text—we are surrounded by racism and transphobia.

The history of the colonial cis-tem is permeated with images that have been manipulated in accordance with the interests of the colonizer and that have assisted in the subalternization of the racialized colonized people. The colonial world order is founded on the binaries of nature and culture, and body and mind, and it has produced images that legitimize white supremacy over all other beings on the planet; following this logic, the concepts of the dirty and the clean aestheticize experience in accordance with the interests of domination. In this colonized world, the ideal centers upon whiteness, and as a consequence of this, everything that approaches the white meter is understood to be healthy. The urban gentrification that results in the eviction of families in favor of the state, the obstacles indigenous people have faced over the centuries in their fight to gain recognition as legitimate rulers of their own land, the relentless privatization of communal areas—together these form a body of power that ensnares our lives in this colonized world. Bruna Kury has coined the term gentrification of the affects in order to think about how these forces exert themselves upon our bodies and our desires, in particular the privileging of the white cis-heteronormative claim to the right to pleasure and desire, and the relegation of dissident bodies to objectification and affective and sexual contempt. That is why we reaffirm our dissenting bodies in pleasure with ourselves.

It is important to be aware of this hegemonic racist policy that seeks to subalternize us at whatever cost—to curtail our affectivity, separate us, and present us as dirty. This is all part of the colonial machinery—the grinder. An investigation of the pandemic that considers it from the intersection of race, class, and gender is fundamentally necessary! In the world, death is racialized. And Black people feel even more deeply the racism inherent in the culture of hand- and face-washing.

We proclaim: “Let us darken[4] things!”

Mc DELLACROIX, “video manifesto 001,” 2018. Direction, photography, editing: Cecilia Da Silva Dellacroix & João GQ. Special participation: Haroldo & Veniccio Barbosa. Lyrics: Mc DELLACROIX. Recording: Malka (3db Audio). Musical direction: Sijeh. Music production and finalization (mix & master): SKY. “Let us strengthen, listen and act/ while being/ while (I) believe/ as long as we’re alive to see!/ The + transvestites, Black people, people with different abilities, LGBTIs are in the spaces of image production + reflection and less abuse in the work place”. (Reference to the fragment of the single QUEBRADA from Mc DELLACROIX.)

***

Keep your distance if you want to live. Big media corporations announce this daily, brandishing a mixture of tele-fear and bioterror. While the middle class prides itself on the creative ways it finds to pass the quarantine, whether with online courses, yoga, self-help, or motivational texts, a large portion of the population—the sector of colonial sacrifice—has once again been left to rely on their own luck. These comprise the category of INFECTABLES, bodies that, thanks to the system’s exclusionary maneuvers, depend on and constitute the street. Homeless people comprise the front lines, along with informal workers (peddlers and prostitutes, among others), people who depend on the daily income of their work to survive. Here to enter those services called essential, like the labor of subaltern workers in supermarkets, pharmacies, snack kiosks, in addition to food delivery people, who depend on the new surge in delivery apps. Bodies marked by race (brown or indigenous) and gender and sexual dissidents. All of these are factors that increase their likelihood of being infected, and which in turn also underscore the colonial and historical absence of public health policy. For this reason, as long as they still have breath in their lungs, the most vulnerable SHOUT.

Borders, those lines created during the colonial expeditions, have gained a new meaning today: protection from the external pathogenic agent. Except they aren’t protecting us, but rather economic interests. Nation-states renew their tyrannical sovereignty through the deployment of war strategies that promote the health and security of bourgeois, cis-gendered, white, normative lives. Those same nation-states which, just a few months ago, slashed social services yet again in the name of neoliberal policy, present themselves today as the messiahs of life, making false monetary advertisements in response to the public health crisis. Big corporations are taking advantage of the current moment of extreme social fragility to promote themselves through donation programs that distribute resources (always with an eye to the profits they will eventually generate) to combat the invisible enemy. These are companies like La Vale, the ecocidal mine, the enemy of life in its very essence, which donates resources to Brazil’s public healthcare system at the same time that it prevents its employees from social distancing, demanding that they expose themselves to the risks of contagion in the name of continued mineral exploitation. Or banks like Santander, Itaú, or Unibanco, who donate to their own social institutions. These are all businesses that view health as a market opportunity—long- and short-term investments.

Gê Vianna, Sobreposição da História, 2019. Collage digital. "Contar otras formas del cuerpo Negro reposar en los campos de caña. En el camino, identifiqué lugares que trajeron un imaginario común entre la caña de azúcar y la selenita y que era necesario comprender que debemos mezclar la tierra para que esto ocurra primero. Desde la tierra de Guiné hasta los caminos de la India que germina en Maranhão, del día que creí haber tocado el cielo, vi todo lo que se conectaba con el cristal de la caña. Era el deseo de conocer cada rincón de ti, dulce como melaza. Vamos a trabajar en otro momento, lavar el sudor del rostro, pies y manos, mirar a los lugar de convivencia, de las veces que mi abuela se metió en la selva colectando babaçu, otras cortando cristal o de este tiempo que mi madre afiló las manos para cortar arroz, hijas de la tierra casi desmayaron metieron el dedo gordo entre el pasto para agarrarse." — Gê Vianna

Everyone wants to return to normality—for life to be as it always has been. But what really is that normality? The normal we know was built on the old colonial constructions that affirm the extermination of certain bodies. We have been inserted in genocidal practices that have targeted Black, indigenous, and trans people, transvestites, boycetas, maricas, lenchas, people with diverse mental and physical abilities, and HIV positive people, among other dissidents. Societies that are structured on dichotomies and binaries that are manipulated according to the interests of global and local hegemony. Perhaps the new normal, or the post-pandemic normal, will be neither better nor worse than what came before it. Perhaps it will simply be a variation of its predecessor, a result of centuries of successful oppression of resistance by means of a pulsating necropower. Indeed, for those who declare themselves the masters of everything by way of their war machines, the future seems prosperous.

Ateliê TRANSmoras, Brasil: O País Campeão Mundial de TRAVESTIS! En noviembre del 2019 la estilista Vicenta Perrotta llevó hasta la pasarela de la Casa de Creadores una opera-fashion con más de 100 personas TRANS entre producción y modelos. Con dirección creativa de Manaura Clandestina, el desfile rescató nuestra bandera verde y amarilla en oposición al discurso reaccionario y genocida presente como nunca antes en Brasil. El trabajo de Perrotta ha contribuido para profundizar las discusiones acerca de los patrones estéticos eurocéntricos y los procesos destructivos de la industria, siempre tomando los estudios de género y la transfobia y higienización social brasileros como detonante de sus articulaciones. Modelas arriba: Manauara Clandestina, Ms. Pythia, Onika Bibiana, TRANSÄLIEN, Terra Johari, Melory Kasahara, Yasmin Bispo, Muniky Flor, Anita Silva, Danna Lisboa, Kiara Felippe. Fotografía por Tata Guarino. [Disponible en: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gYe4FKTukM4&t=1301s]

We have come out of centuries of survival of patriarchal murder. It is time to remember the techniques of resistance that we have inherited from our ancestors and put them to use in the moment that is confronting us now. Think about cocoons, look at the internal potential wrapped within them that prepares for individual and collective life. It is time to search among our roots for the responses that will keep us alive and healthy enough to follow the path that awaits us. We must focus a gaze, not narcissistic like the one which white European culture has attempted to impose upon us, but rather one that imagines new forms, as when Yemanjá and Oxum[6] used their mirrors, reflections which carried with them lessons about how to vanquish war.

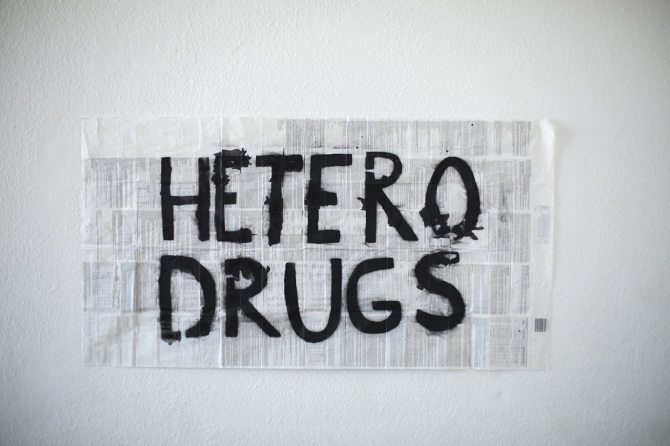

Linga Acácio, Terra posithiva, sob seus pés, de la serie Rumo ao desvio, 2019. Performance parte de la exposición Arquivo de sentimentos (Vevey, CH). “Entre los años de 2014 y 2015 yo recibí anti-retrovirales por el SUS (Sistema Unido de Salud) de la fármaco-industria HETERO DRUGS (www.heteroworld.com). Una magia de cura a partir de aquello que me mata bajo el nombre de hetero, una limpia de veneno. ¿Cómo transformar el veneno como forma de infiltración? ¿Cómo transmutar esta mezcla de agua, sangre y carbón en un caldo que pueda generar vida? Recordar: limpiar debajo de los tapetes.” — Linga Acácio [Ver más en https://vimeo.com/370081463]

For us dissidents, social distancing is nothing new. We have always existed apart from cis-heteronormativity and we pay the price of our lives by always living in a state of precarity. This constant state of precarity means that an agreement on mutual protection is necessary at this moment that demands a higher dose of care. It is necessary to conjure life after the coronavirus! It is important to remember the words Conceição Evaristo used to describe the continuity generated from the experience of those who have always known how to survive: “They agreed to kill us. But we agreed not to die.”

ÀTÚMBí: In traditional Yoruba culture as well as in other diasporic cultures of African descent—especially in the candomblés of the Ketu nation of ethnic Yoruba origin—life does not end in death. Rather, àtúnwá (reincarnation) or àtúnhí (rebirth) is the divine process through which life continues.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ZiClLTmaJ8

Isadora Ravenna & Lux Far, “Existo Mañana,” July 2019. Video performance. Image by Patrícia Araújo. “Tomorrow, as a project of the future rooted in a western timeline, who does it belong to? What bodies does it consider? Is it impossible to not repeat the norm in your body and still manage to project this body into tomorrow? Is it exactly because it is impossible that we are going to achieve it? How can we start new models of existence? It seems that while I was tattooing my face, I was making a tattoo in time and at the same time I was tattooed by it. How to remove a world in its time? How to invent in time another world?” — Isadora Ravenna.

–

The first edition of this text was presented in GLAC Ediçoes in the past month of April.

–

Artists featured in this article

Bruna Kury Anarcatransfeminist, lives in São Paulo (BR) and develops works in various contexts, both within the institutional art market or in cheap productions. She focuses on productions based on gender, class, and race (against the current patriarchal heteronormative compulsive theme and the structural oppressions–class war). www.brunakury.weebly.com

Walla Capelobo Dark forest, fertile mud. Anti-colonial transfeminista, artist, and independent curator. She composes knowledge, artistic experiments from the legacies of good living and existence received by the thin layer of her skin. She works in study groups, Interfluxes (UFF), and GeruMaa: African and Indian American philosophy and aesthetics (UFRJ).

Mogli Saura Performer, singer, composer, writer, permacultor, and yoga instructor. They have been experimenting and researching in urban spaces since 2006, starting from the frontiers between art and life, madness and crime–and their categorical-structural relations involving race, gender, and class.

Coletivo Coiote Performs direct actions inspired by anarchist, transfeminist, decolonial, marginal and anti-capitalist ideals. Created in 2011 in Rio de Janeiro. In 2020, some members meet again for the completion of a cycle with the pornorecicle project.

Mc DELLACROIX Multi-artist, cultural producer, and emerging voice in hip hop. With more than 7 years of artistic career and 4 years ago with the DELLACROIX project, the rapper uses her body to tell her story as a body that diverges from the norm. Co-founder and artistic producer of Casa Chama, a cultural association of LGBTQIA+ care where ART is promoted.

Gê Viana was born in the village of Santa Luzia–MA. Currently lives in São Luis–MA. She produces analog and digital decolonial collages, using archive images to transpose her works. Inspired by the events of family life and their daily life in a confrontation between the hegemonic colonizing culture and the systems of art and communication.

Vulcanica Pokaropa Travesti trained in Photography, she has a Master’s degree in theatre, her research addresses the presence of Transsexuals, Transvestites, and Non-Binaries in Theatre and Performance. She researches hula-hula, contortion, and humor. She is a member of the Fundo Mundo Company, a circus company formed exclusively by transsexuals, transvestites, and non-binaries. Performer, Poet, Visual and Plastic Artist, Cultural Producer, and Curator.

Ateliê TRANSmoras Founded by stylist and artist Vicenta Perrotta, it’s a space for artistic residences and center for coexistence between trans artists and LGBTQIA+, located in Campinas-SP. The main project of the Workshop is cutting and sewing, creation, and perception in the production of fashion while reusing textile materials, upcycling, along with the re-signification of the white-centered aesthetic imposed by the industry. @atelietransmoras

Linga Acácio Artist from Ceara. Researches, writes, and produces knowledge that crosses the fields of performance, intersectionality, gender and transvestite dissidence, HIV+, contaminations between body and space, and strategies of anti-colonial resistance.

Jo Assumpção is an artist of the word, studies afro dance as well as Brazilian folk dances. Currently dances in Baque mulher RJ, and with the collective Kalunga, besides creating the company. MNEMONI, Colectivo Afroxirê, and scholarship holder of the Afro dance teacher Valéria Monã. Researches in the contemporary body the action of ancestral resistance, the movement of kalunga, and healing.

Isadora Ravena Travesti, teacher and multilingual artist. In 2020, she launched the book Sinfonía para el Fin del Mundo [Symphony for the End of the World] and developed works such as perigosa boneca e seus sujos golpes, ira e o tempo dos mortos: relámpagos, vozes, trovões, territores e grande saraiva and Sepultura, exhibited until February at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Ceará.

–

This text was translated from Spanish to English by Chloe Wilcox.

(Translator’s note) The main social movement that occurred in the sertão of northeastern Brazil at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century. The movement was especially related to the struggle for land, the abuse of power by the colonels and the poverty in the region.

This is a reference to the work of Denise Ferreira da Silva, a Brazilian artist and philosopher.

(Translator’s note) The word originated in Spain and was used largely as a pejorative way to describe people from South America, often those with indigenous features. It has since been reclaimed by South American people.

In the Spanish text, the authors use the word oscuronegremos, which is a neologism that combines the word for “obscure,” oscurar, and the word for “black,” negro, into a verb. They have been combined into a single word that seeks to express and represent the effort of what the authors call enegrecimeinto (“blackening”) as a possible way of seeing the world that is distinct from colonial models. It implies seeing the world from a “Black” point of view, and not through a “White” lens.

Calunga is a name attributed to descendants of the slaves of Goiás, Brazil. It is also a term connected to religious beliefs and refers to the world of the ancestors.

Orishas of the Umbanda and Candomble in Yoruba mythology.

Comments

There are no coments available.