Building on a reflection proposed by Terremoto, artist Chris E. Vargas, curator and activist Jasmine Wahi, curator César García, and curator Natalia Zuluaga share their opinions on identity politics, diversity, inclusivity, and legitimization in the contemporary art museum system in the United States.

Terremoto asks: During the last five years of the second decade of the millennium, and mainly through their promotion in museums and biennials, identity politics have become one of the fundamental components of cultural policies regulating contemporary art institutions in the US. Aiming to diversify the heteropatriarchal whiteness that characterizes said system and consequently society at large, identity politics are motivated by the quest for the inclusion of people of color, LGBTQ+, and women in the art world.

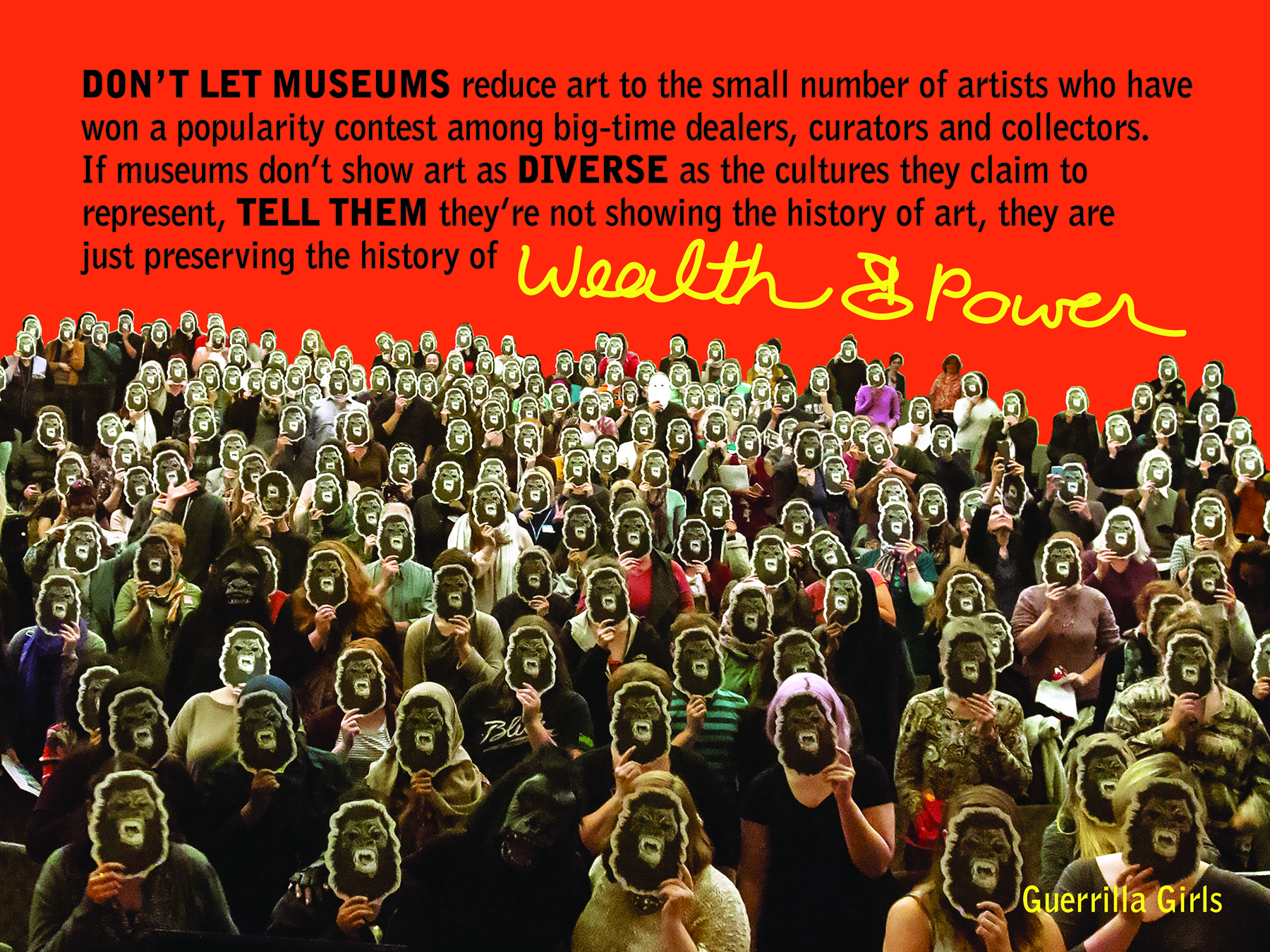

Although the value of the work of the aforementioned groups of artists is recognized through this process, this liberal position of institutional legitimation is responsible for—conditioned by political correctness—the art system’s superficial image that reacts to the in-mediatic sociopolitical context. Although institutional cultural policies have responded to the demand for the historical and institutional redressment of POC, LGBTQ+, and women artists, the material conditions that were forged for these artists over time are delimited by a systematic and structural framework that allows heterosexual cisgender men—the vast majority of them white—to monopolize symbolic economic capital. In 2017 and 2018 respectively, Artnet reported that only 11 percent of all museum acquisitions in the last decade in the US were works by women, and only 3 percent were by African-American artists. Not to mention that in the top galleries in New York—a city that is still considered to be the hegemonic center of the US art system—80 percent of represented artists are white, of which 68 percent are men and 32 percent women, both groups having at least a master’s degree just as is the professionalization of the global art world demands. It is important to note that only 8.8 percent of artists represented by New York galleries are Black and only 1.2 percent Latin@s. Reports of this kind about undocumented artists are not available (which reveals that the market is only accessible for “legal citizens”). Furthermore, data about LGBTQ+ artists are not available (in part because it is not ethical to assume someone’s sexuality or gender). To paraphrase Ash Sarkar, we can conclude that POC, LGBTQ+, and women artists must accept oppression in exchange for representation.

Considering the above mentioned statistics, we would like you to reflect on how we might understand the power relations that exist between museums/biennials and the market with regards to the system of legitimation—both commercial and historical—linked to identity politics. Why does it work like this? In other words, what conditions would make possible the dismantling of these power relations?

Institutions Eat Critique – Chris E. Vargas

The Museum of Trans History & Art, or MOTHA, is a conceptual art project I created in 2013 in response to the new wave of attention museums, academia, and mass media have directed toward trans* people. MOTHA is a platform I use to highlight the important cultural and creative work being made by other trans* people, past and present. It allows me to bring a wider range of trans* artists into museums who wouldn’t be shown otherwise. But more importantly, MOTHA is a work of institutional critique that seeks to interrogate the reasons behind the historic exclusion of this community from these cultural spaces.

But in truth institutions love to absorb critique; in fact, they eat it up.

Immediately upon its inception, MOTHA was invited to various art institutions, mostly through the museums’ education and community engagement departments. The exhibition calendars of these departments tend to be shorter than those of the main curatorial departments and, thus, they are in a better position to respond to topical and timely political issues. These departments are doing important work to address inequities in regard to what kind of artists receive museum exposure. However, while they give many queer artists of color, like myself, the opportunity to present work in highly visible spaces, they also take the heat off the rest of the museum to present large surveys or higher profile retrospectives of work by POC and LGBTQ+ artists. Museums’ main curators, not just the education and community engagement departments, need to be doing the work of recognizing and legitimizing these artists by situating them within the main galleries where art history is made.

The spreadsheet “Art/Museum Salary Transparency 2019,”[1] which circulated this past spring, was an exciting development. It made visible the wage disparity in various departments at established cultural institutions in the US. Around the same time, there was an exciting emergence of labor activism and union organizing by workers at New York institutions such as the New Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Brooklyn Academy of Music. The equitable compensation of museum staff is a step toward addressing the inequities embedded in such institutions, as would be doing away with prohibitive admission prices which are a barrier to true accessibility. But these things alone will not undo the historic inequities. For a true dispersal and redistribution of power, we would need a complete dismantling of capitalist economic structures.

Because MOTHA often parodies and pokes fun at the vernacular structure of museums, people often assume there is a barrier to it being accepted by them. But in truth institutions love to absorb critique; in fact, they eat it up. Doing so makes them look savvy and puts them at the forefront of a critical conversation. But it also works to diffuse the critical message. While I began MOTHA feeling optimistic about the power of institutional critique, I am no longer deluded. I am not making a dent.

Soliloquy – Jasmine Wahi

[Dim lights come up on an ambiguously “ethnic” woman in a lounge chair. In one hand she holds The White Card[2] by Claudia Rankine. In the other, a glass of rosé. She gazes somewhat thoughtfully and somewhat tipsily into her glass of wine. It is clear she is in conversation with other Black and Brown women, discussing Rankine’s book.]

Who chose it? Private prison profiteering? The art world? It’s like the foretelling of the biennial debacle! Why did WE need to read this? It was all just too real. It makes me question the things that I’ve compromised or sacrificed. My successes feel predicated on tokenism. Do I have power? It’s all relative to the circumstances, right? Would I have power in the art world if I’d stayed in the gallery system? Probably not: once I worked at a gallery that told me I was the diversity hire—this does not bode well for the height of the glass ceiling . Chances are, if I worked in a museum, you wouldn’t find me in the curatorial department. You’d find me somewhere front facing—but not too high up. I’d work in the department tasked with making the audience more… colorful [emphasis on the euphemism]. Museums love to appear not inclusive, but diverse.

Why are so many art spaces so quick to put a Black or Brown body on the wall but not in the office chair? Getting distracted here… sorry, back to Rankine. I can’t count how many experiences similar to Charlotte’s I’ve had—a white collector wants to “relate,” talking about how pretty my “costume,”’ aka my sari is. She wants to tell me about that time she went to India and got sick from the water, but was so impressed by the art? [She shudders and gulps wine.]

Can our system change? It’s like everything else—built on a legacy of domination and oppression for the sake of capital gain and imperial power. Is it money or race that drives us forth? Are the two even exclusive? We can’t deny that the art world is predicated on unregulated “patronage,” so can this system evolve into something better? [She jumps up throwing the book down.] Do we tear this fucker down?! Take down the museum walls? Reinvent the system? [She sits down slowly.]

Why would ANYONE give up power? Do people make it possible for this academic discipline to carry on? People with money— collectors, donors, BOARD MEMBERS, AND TRUSTEES! [She holds up the almost empty glass.] CHEEEEERS TO YOU! And all the things you do to make your millions to support us. [She bows her head to the imaginary collectors]. And all the millions you use to exoticize us, to jack up our market value without doing the due diligence or having the responsibility to make sure we’re OK.

In spaces of whiteness, will capitalism ever benefit people of color? Maybe we just continue to work thrice as hard hoping to get a crumb? Will we ever change how we value art? Can we reaffirm the value of knowledge over tenure? Maybe we boycott institutions that have a non-history of hiring non-white leaders? Do we give a shit about the intrinsic link between marginality, oppression, and capitalism?

Or maybe we just burn it all down. And start over. [She smiles, sighs, and the lights go down.]

Who Can Afford to Be a Curator? – César García

Following the election of Barack Obama, we saw bolder—and necessary—calls for equitable inclusion in political, economic, and cultural spheres. Across museums and other art institutions, the difficult work of confronting and correcting histories of exclusion made some promising strides forward as important hires of curators of color began to be made and works by white straight artists were deaccessioned in order to generate capital for the purpose of“filling the gaps” in collections.[3] Conversations about diversity in the art world grew. Foundations launched fellowships to make the curatorial field more accessible and in popular culture we saw Kehinde Wiley’s portraits appear on Empire, Carrie Mae Weems and Amy Sherald cameos in Spike Lee’s remake of She’s Gotta Have It, and Beyoncé’s pregnancy photos shot by Awol Erizku. We can safely say stuff seemed to be happening. Then came Trump’s election threatening the small progress that had been made. The cultural climate that has emerged has put those working toward more diversity on the defensive—and rightly so. Among those on the front lines are curators whose work is opening up institutions in many ways to artists and practices too often overlooked.

Last year, as many visionary curators of color took on new appointments or received promotions, we saw them profiled in media outlets. We learned of their critically important work, what informs and inspires it, and how they got to where they are today. It has been empowering to see so many of our colleagues receive the attention their work deserves, and many more should be publicly commended. Some of their stories subtly lead us to an uncomfortable but important conversation that is deeply tied to the meaning-making economies of contemporary art and that is: Who can afford to be a curator?

Truly emancipatory frameworks and futures cannot be configured from anything that qualifies its actions through the language of extraction.

Questions of representation today are reified too much solely around race, but as capital has come to determine access in the arts in unprecedented ways, our diversity conversations must become broadly intersectional. Those who determine which artists get exhibitions or what works get collected should include people whose lives are as varied and complex as the practices of the artists we champion. If only the curators of color who can afford to take the $25k-per-year fellowship in New York or who possess the cultural capital and networks to navigate spaces of privilege are the ones at the table—we all lose.

Representation is about more than including those who look like us or like those who have also been marginalized. It’s about acknowledging and embracing a wide range of views and life experiences—perhaps most importantly those of the people who, despite seeming like us, live in the world in radically different ways.

There’s not enough space here to offer a solution and by no means is it my intention to dismiss or belittle the hard and important work that many of our colleagues have achieved through their talents and merits. My hope going into 2020 is that the challenging and often painful conversations many of us have been having behind closed doors for far too long become more public and that through them we can seek solutions for all of us to push the work forward together.

No Response, Just a Cautious Distrust – Natalia Zuluaga

The “art world” and its museums continue to be sites of competing dynamics: they follow a logic of exclusion while amassing, “rescuing,” and legitimizing by way of capture through classification. Although this has been primarily mediated and negotiated by way of objects, it has resulted in an art history that is, along with the institutional forms that support it, deeply racist, sexist, and violent with a distorted sense of fairness and diversity based on opaque notions of quality and taste.

Today, the field of contemporary art is fueled, if not defined by, the tireless roving and mining for the next object and body from which value can be extracted. The puss of legitimacy that feeds value is not only extracted from art objects but from the bodies that participate and are beholden to the reputational economy that defines contemporary art; it is a kind of social credit system where someone or something cashes in on the cachet of exposure and proximity. The discourses and attempts at diversity and inclusion within the field of contemporary art are not inoculated from the force of this extractive vortex. The market and institutional concerns with inclusion are, in fact, the very instruments of the same entrapments and extractive principles that drive the leveraging of value. To be unsuspicious of the excitement with which inclusion and diversity have been taken up in the field of contemporary art is to be blinded by the patina of positivism and celebration that institutional marketing produces today in its effort to create social capital. Such a pass risks being trapped in the distraction of hypervisibility, of being defined by sterilized images, and being submitted to further fragmentation. It jeopardizes our ability to recognize and act against the close proximity between the objects hanging on the wall and the violence enacted on bodies at borders or at the site of the next pipeline. In short, all of this is to say that there is no conduit by which one can address or speak to systems of oppression that do not care for or is not programmed to consider the conditions of our existence outside logics of extractivism. This is in art as it is in life. To think otherwise is to partake in the illusion perfected by “share” economies, “woke” politics, political correctness, social media likes, and the short-term rewards of self-promotion. So Cash it in if you want to (and understandably if you have to). Cash it in if you hunger for the temporary reprieve and mirage of justice that such recognition offers. Cash it in even while we figure out, as you suggest, “what conditions would make possible the dismantling of these power relations,” because they do not exist within the logic of contemporary art. Truly emancipatory frameworks and futures cannot be configured from anything that qualifies its actions through the language of extraction.

Comments

There are no coments available.