16.02.2015

Interviewed last November in her home in Rio de Janeiro, iconic Brazilian artist Anna Bella Geiger (b. 1933) reveals how art certainly cannot escape history and context, especially when marked with dictatorship, but also how curiosity, tenacity, hope, and luck have been the best allies of her long-standing career.

Anna Bella Geiger in her home with one of the Burocracia (1978) drawings

Dorothée Dupuis: Did you see the current São Paulo Biennial?

Anna Bella Geiger: I deal with the experience of the contemporary. I recognized that in this Biennial. The art itself is getting lazy. Interestingly, lazy is opposed to leisure, in the sense that people are interweaving ideas of the political, social, religious, etc., which matter in the current confusion and difficult political situation. For instance, the geopolitical, on which I worked a lot, has become a sort of genre in itself, and at the end of the day people obey the laws of art. The Ten Commandments of art. Maybe I’m being conservative. But you know, I come from a past-past, and I’ve been through Figuration, Abstraction, Neo-Concretism, etc., and so I experienced many ruptures or passages throughout time. All laws belong to something broader, during my time of Abstraction many things would come from what Picasso had done. So you would question yourself about color and form, not as a cliché but something that inhabits the work.

The works in the Biennial take their cues from sociology and anthropology but the formal results are not the main goal. Of course, it still works, because these curators chose intelligent artists, but this is a sign of an exhaustion: when any wave of art starts to get tired, it enters into cliché.

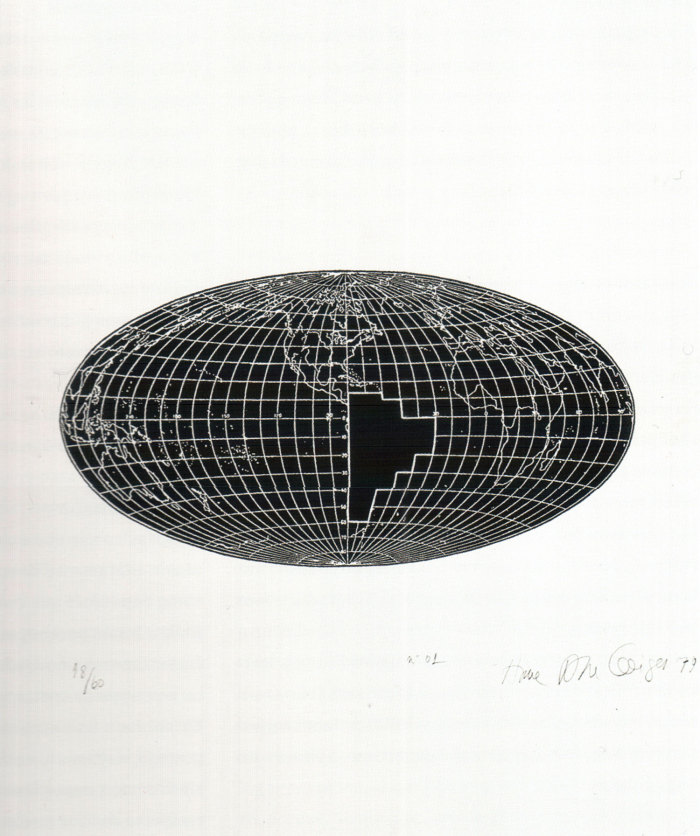

Anna Bella Geiger, Local da açao, 1979, etching, 70x60cm

DD: It must be so different now from when you started to work.

ABG: Many artists don’t question their relationship to the object of art anymore. But artists have had to do this since cave painting and I wish I could have been one of those artists. The feeling is lost, this necessity to question, to transpose… I used to give a class inspired by Magritte, I would show a very academic painting of a cow to the students and tell them, this is not a cow. When I started to work we had an “ism” to complete. There was a name. There was something much broader than a message from me to you – a very complex idea, the one of the abstract, the quest of the sublime and of the original. The difference was all in that thing you belonged to, the “ism”, and the loss of this utopia as a political ideology in art came by fragmentation. For example, Marxism is still discussed in social science even if communism no longer exists as an “ism”: so what can still be discussed in art and how should people know what to discuss?

DD: What do you think of this articulation between the independence of the artists and the need to stay part of a collective conversation?

ABG: I have a long trajectory. How could I survive? Of course from an age point of view, it’s really survival (laughs), but also has to do with my own purpose to continue being an artist throughout time. Many times I almost gave up. I went out of art, in the sense of not understanding anymore why to produce an object of art, and at the end of the ‘60s and beginning of the ’70s, the political situation really made you ask yourself where one can go as an artist, which led one to question the purpose of it all. It’s how we came to boycott the Biennial in the ’60s.

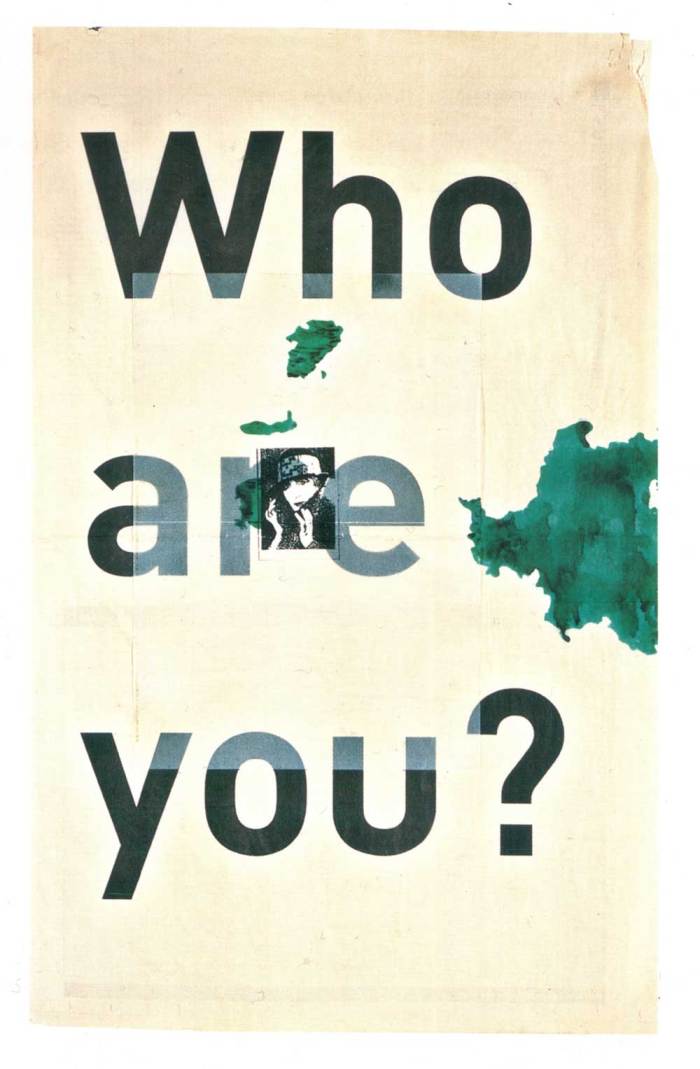

Anna Bella Geiger, Rrose Sélavy Mesmo, 1977-2002, silkscreen on newspaper, 56x32cm

DD: Please talk about that.

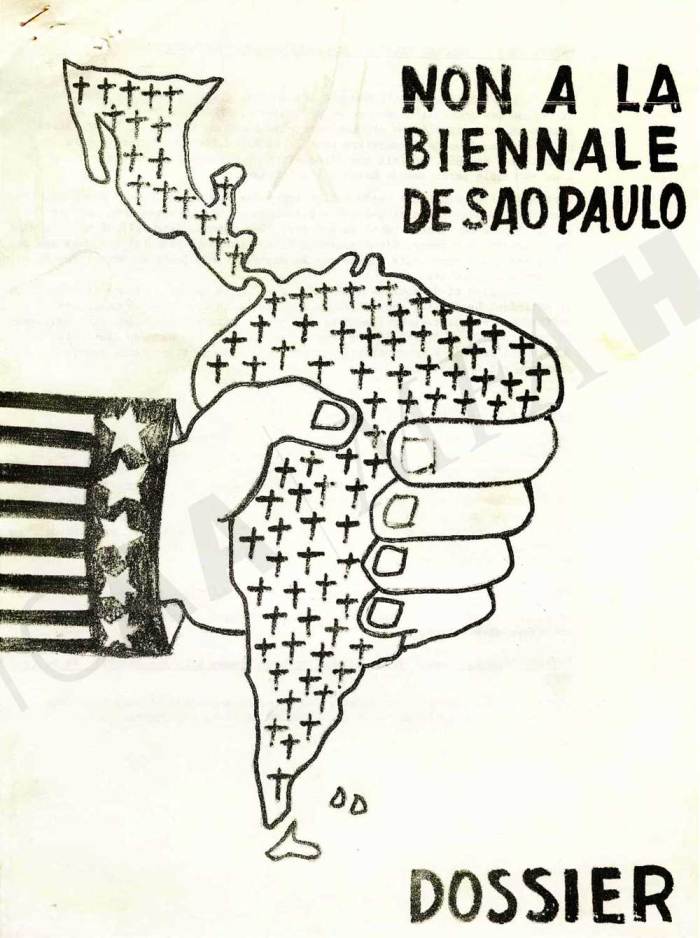

ABG: All of us artists had taken part in the Biennial before; it was our window to the outside. In ’68, after the Act passed, violence started to rise, and people had to get involved in the political situation. People started to get killed, to disappear, art was censored, and particularly music because of its explicit lyrics. We started meeting in a room at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro, and at some point it became too dangerous to meet. If someone knew of a meeting, they would get suspicious, point at each other in the streets, etc.

DD: I heard about an artist who was arrested and detained, and when he came back from prison, he was so traumatized that he burnt a great part of his work.

ABG: I had an exhibition of some of my artist’s books in a gallery in São Paulo. My work was never very subtle, and like the New Atlas series, it dealt with the geography of Brazil. It criticized the system from within, though it wasn’t pamphletary work! I made a drawing of four women saying “bureaucracy”. I liked the humor of these four women. I printed some transparencies with this image and with other artists we went to every corner of the Avenida Paulista and we distributed “bureaucracia”. I never put my body in danger. I wanted to undermine the system of representation. The Act was intensifying the persecution. Many people lost their ideas of what a democracy could be. There was torture. So we decided not to take part in the Biennial. There were alternatives: national salons and regional exhibitions, etc. We decided not to boycott only local salons but also the São Paulo Biennial and we encouraged international artists to do the same.

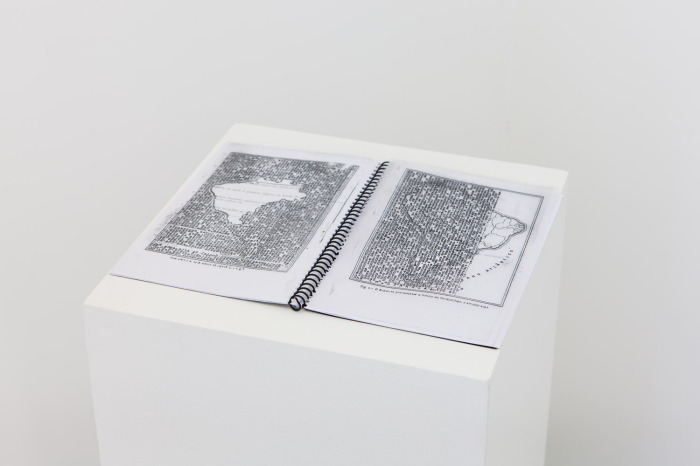

Anna Bella Geiger, Admission, circa 1975-1977, artist book, 20x24cm

DD: Did you run into trouble?

ABG: Only within the system of art! We were only starting to show internationally and the boycott put a hold on that. I didn’t really have space in my apartment to make work because of the children. I worked against the suffocation, and I kept working in my head against that system. It was not total isolation though. In 1967, Pop Art came from the States, and of course, here it took another turn. The political situation added a level of reflection. If you look from a distance at the discussion about what an object of art is, it started at that time. Conversations about shifts in media and all that, it comes from something broader than to be an artist at that political moment. Many forces were trying to push you out of the field, and I was also having my own crisis, which was not only psychological, but was more that no one asked about your work. Some artists left Brazil. I couldn’t leave because my family was here, so the attention seized.

DD: Still there were two important events for you in the ‘70s and ‘80s: Video Art in 1975 at the ICA in Philadelphia, and then the Venice Biennial in 1980.

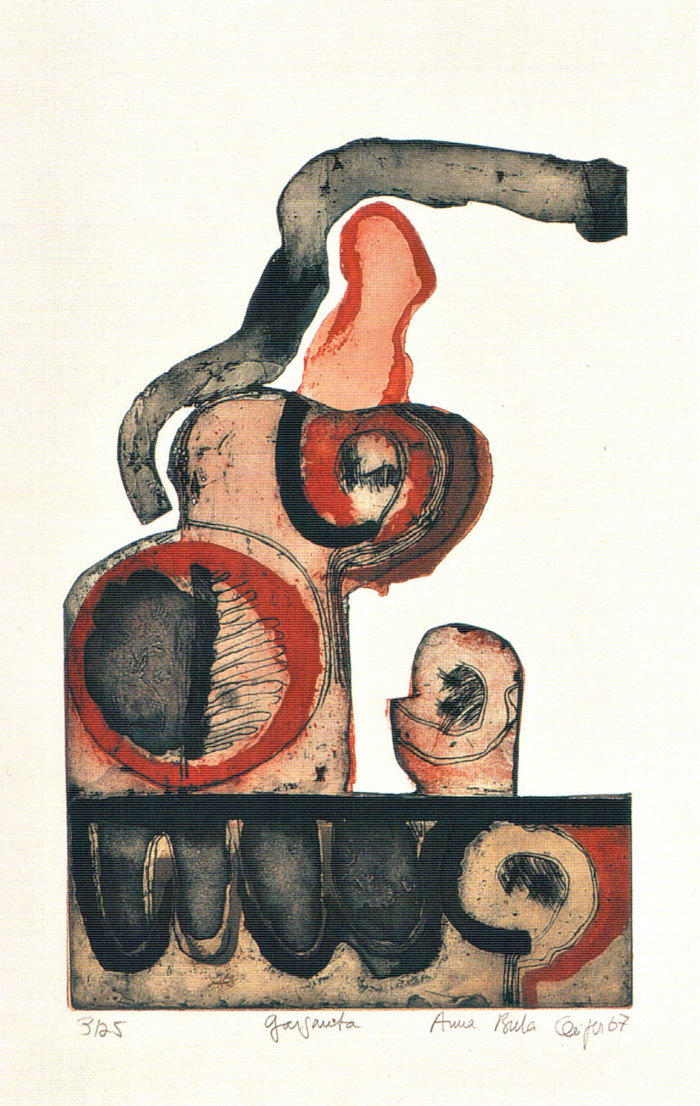

ABG: Those were exceptions, miracles! I think the show at the ICA happened through Walter Zanini, who was the Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in São Paulo at the time, and is a chapter of Brazilian art history by himself. Personally I was very involved with the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro from the ’60s on. When I started to make the Visceral series, everyone said it was a horror. Both my colleagues and people coming to the museum would say, “Anna Bella makes these things with blood dripping from the engraving.” Until ’66 I went to the MAM here in Rio everyday, but the attitude of the people there changed towards me after ’65 because of this Visceral works.

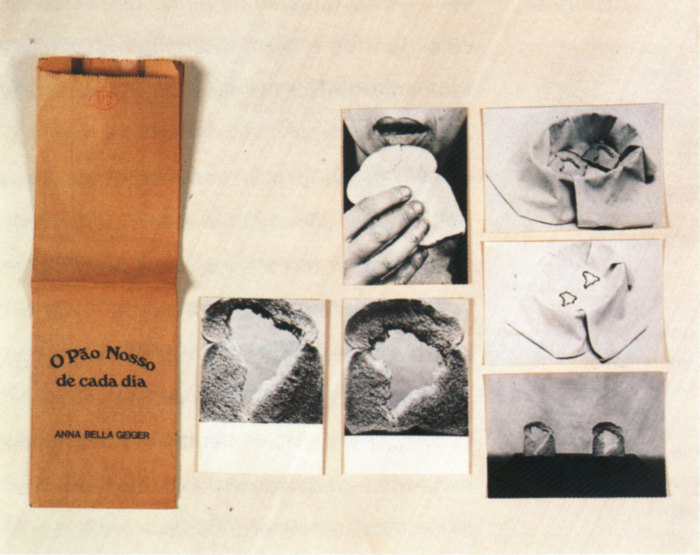

Anna Bella Geiger, O pão nosso de cada dia, 1978, paperbag, 6 postcards 17x12cm each, photo by Januário Garcia

DD: Though, abstraction was maybe a way not to talk directly about the political.

ABG: No, I wouldn’t say that. The abstraction you are talking about happened well before that time. I published a whole book about abstraction in Brazil with Fernando Ciuccharellli, O Abstractionismo. By the end of the ’70s – still during the dictatorship – the roots of Funarte (Fundação Nacional de Artes), were laid, it was an initiative from Brasilia but their main office was here in Rio. Art was changing, everything was changing, and it was the time of the dictatorship that they call the “abertura”. The general that orchestrated the abertura had a daughter who is still alive and she created the Funarte. Their actions were very discreet. It was an initiative for research investigating the contemporary and they offered jobs. It was like an oasis in the middle of the desert when it emerged.

Anna Bella Geiger, Garganta, 1967, aguafuerte, 80x60cm

DD: So going back to ’68, you had stopped working at the museum then.

ABG: In ’66 I was exhibiting the Visceral works at the Biennial. Then in ’68, the Museum of Modern Art in Rio had a main Director, Niomar Muniz Sodré, and her husband was the Director of Correio da Manhã, a Rio newspaper. The museum was an independent initiative and it didn’t rely on the state. They put up an exhibition with a selection of Brazilian artists. The owner of an insurance company offered a prize, which was to send an artist to travel abroad. I won that prize. It was like if you are in the sea drowning, and all of a sudden you see this wooden plank in front of you. So I went traveling. I had never been to Europe. I went to the USA, to France, to England and to Germany. The children were small and I left them for almost two months. I decided to go see museums with my work. Of course, no one could write me introduction letters before. Brazilian artists were so unknown. I took my Visceral series with me to the MOMA in New York, to the Department of Prints, and they actually received me. They knew so little about Brazilian artists, they were so surprised that it worked, and they bought the works immediately. I cried from happiness. We were very poor, I had a big family and we had to pay for school, etc. Then I went to England, and the Victoria and Albert Museum had the same reaction, and the person from the print department bought many works. I went to the Biennial of Paris too. There was the Biennial in Venice in ’68 and I went. I met with artists there, like Daniel Buren whom I met in Rio 40 years later, and also Christian Boltanski, and I explained to them that we wanted to boycott the São Paulo Biennial. They were astonished by our situation, but they gave us ideas and they said they wouldn’t apply and they also bought my work to support me. After this meeting, I heard there had been a reaction in Paris about that Artists there had made a document saying that they would boycott the Biennial.

Unknown author, Non a la Biennale de São Paulo: dossier, 1969, Julio Le Parc archive, Paris. (via www.icaadocs.mfah.org)

DD: On a purely formal point of view, do you think this trip influenced your transition from engraving to the making of more conceptual work, such as using postcards, Xerox, photography? You mentioned Pop Art earlier, obviously the new media question was starting to happen in Brazil too.

ABG: The media was not considered by the critics at the time. In the ’70s, I started teaching a new kind of class. I had a friend who was a photographer, he had his own material and he was fascinated by the class. I proposed he accompany us in this new class that consisted of visiting the museum. We would borrow the car of one of the students and drive to faraway places, into nature. I could feel we were watched in the city, although the police didn’t come or anything.

DD: How did you come to art as a teenager?

ABG: I was like other children, I liked to draw, but I didn’t stop drawing as other children when I grew up. My father was a craftsman, when I found family members after the war, all of them were drawing and making things. My father enrolled me in the Lycée Français. In 1945, there was an art competition, “How do you see Paris’ freedom?” During this time Paris was liberated but the war wasn’t finished. To have international information like that in a school was already different from other schools. My parents were from Europe and had this history of horrible suffering and wanted us to be aware of that. I made a drawing and won the prize. There was a ceremony at the French Embassy, I remember it very well. I was 12 then. It is through this competition I met Fayga Perla Ostrower, and I started to follow her teaching, which actually led other people to Neo-Concretism. Although I was led to my specific ways, there is a formal concern in my work that still responds to the principle of abstraction. Abstraction is not because of intuition; it’s a number of commitments about what is form. Fayga’s work was coming from figurative expressionism to abstraction, she had been a student of Katie Kolwitz and she practiced a political abstraction infused with humanist commitment.

After I studied Anglo-Saxon languages: German (which is close to the language Yiddish which my parents spoke), English, Latin, and the literature associated. I did this not to let myself go into my art. I thought about doing architecture but I decided it would destroy my art, and I think I was right.

Anna Bella Geiger, Untitled, 1951, paper collage, 60x30cm

DD: Was the turn in your practice in the ’70s conscious, as in using photomontage, staging yourself in pictures and films, and distancing yourself from painting?

ABG: After I did the Visceral works, I felt stuck. I remember I didn’t believe in this kind of solution in regards to form and shape to speak the situation anymore. At my class at MAM, I was into drawing. I would imitate the pedagogy of Fayga, and then I started to make experiments. The students would join my class because they were hearing about that.

DD: In fact you were deconstructing your own practice with the students.

ABG: Exactly! I couldn’t believe in the modern principles that I had taught before because there had been a rupture. The political moment had brought a desertification in the arts, and that feeling was even more depressing that the other desertification – the one you could feel in society, in the streets and even at home. I was still going to the demonstrations, but I stopped because I was afraid I would be shot and I was thinking of my children. They actually broke into my house with guns to arrest my husband. I could have gone into a deep depression because of that, but the hardest was that rupture in art.

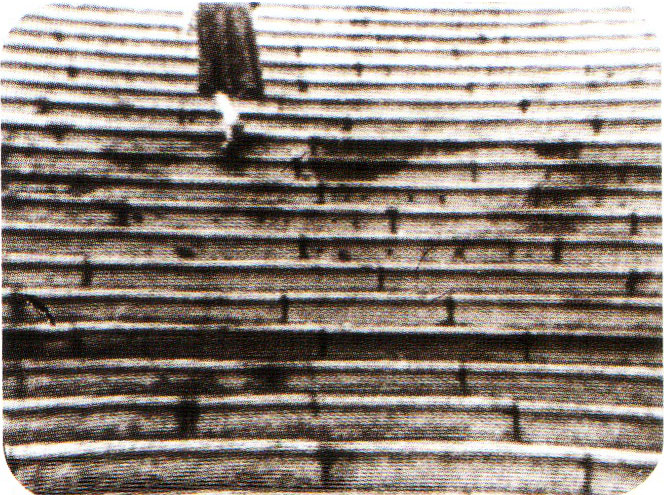

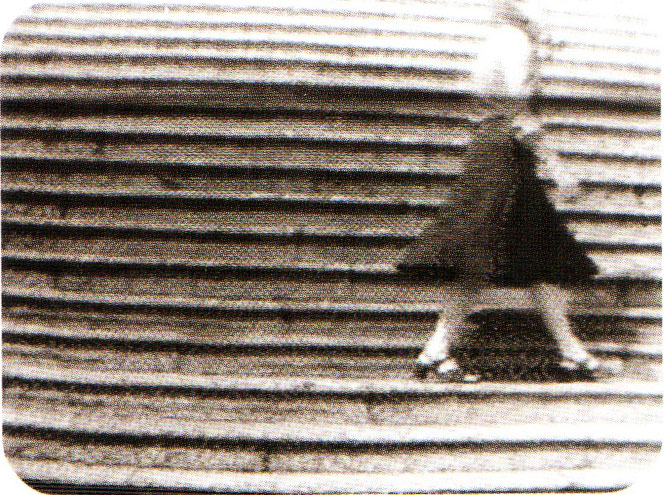

Anna Bella Geiger, Passagens n°1, 1974, black and white video, 12mn

DD: Can you speak more about your film practice?

ABG: I had started to use Super 8. I didn’t have a laboratory, like for example Lygia Pape, who was also experimenting with film at that time but knew film directors to help her. So I did other kind of things.

In ’71 and ’72 I did audiovisuals, with the help of this friend who would register in my class. My mirror is not the other artist in the past or in the present. Art making depends on you physically, but also mentally. I have been able to stand many things together with my family, which also had problems – economic difficulties and all of that. When I was teaching art at the museum people would come to learn etching but they didn’t have any notions of what art was, and often quit the class because etching was so difficult. In the mid-’60s I was working, showing my art, taking part in many exhibitions in Brazil, but then after ’65 when I left the museum, I had to teach English and Portuguese to different people to survive. I thought about going to teach at the university but it was too far away and with the children I wouldn’t have had any time for myself. I was exhausted, but I kept pushing my work in different directions until 1971.

It led me to making Circumambulatio (1972) and I didn’t even know that people were starting to do what would later be called installation, so I called it environment instead. I did a show in the museum, with lights arrangements and other things, and I had a revelation about this thing that I didn’t even understand that I was doing. Although when I had been in France in 1969, I had met someone from this magazine, Flash Art, and he had started sending me the magazine. That was very good information about what was going on and these things of course were coming into my work. The experimental, the fact that artists were using film, etc. In 1974, I made some videos because a rich friend of mine came from Los Angeles with a camera (which at the time weighed more that 40 kilos). It’s funny because a year ago I went to give a lecture in New York at MOMA about my work, and an old man, a cineaste, came to me and asked me how I had done these videos at this time. He told me he always had thought I was a billionaire to have this equipment.

Anna Bella Geiger, Circumambulatio (detail), 1972, black and white photograph, 18x24cm each

DD: Have you ever worked with commercial galleries?

ABG: Well, not really. Mendes Wood is recent, I am the youngest artist of the gallery (laughs)! There were galleries in the ’60s that worked with my abstract work, but there was a small public, and even less a real market for abstraction. After 1966, people would come to the atelier to see what I would make and sometimes they would buy there. The wife of the owner of Bonino in New York had a gallery in Rio de Janeiro, they had introduced pop artists in Brazil and showed abstract and figurative works. She contacted me and I did an exhibition in 1974. I was still using etching and transforming some pictures of the surface of the moon I bought from NASA, and they were such incredible pictures. I considered hybridizing medias in a strange way. I decided to transpose these images on the plate, not just because of my fidelity to etching, but more because this hybridization of media was in the air. Of course I had seen Warhol’s work; that was a transformation of photography into silkscreen, and I felt it was an interesting situation to misappropriate a technique that was totally despised by printers at the time. Etching on the other hand is more like a registration, so it would be like recreating the surface of the moon on the paper. The composition was mixing things up, what was right and what was wrong with these pictures. I kept that very metaphoric, it took the form of a sort of postcard, an intimate message about center and periphery. I started to have pleasure again with etching as I started to understand how I could work in a new way with this technique to make images, as at the time, painting had become the big enemy.

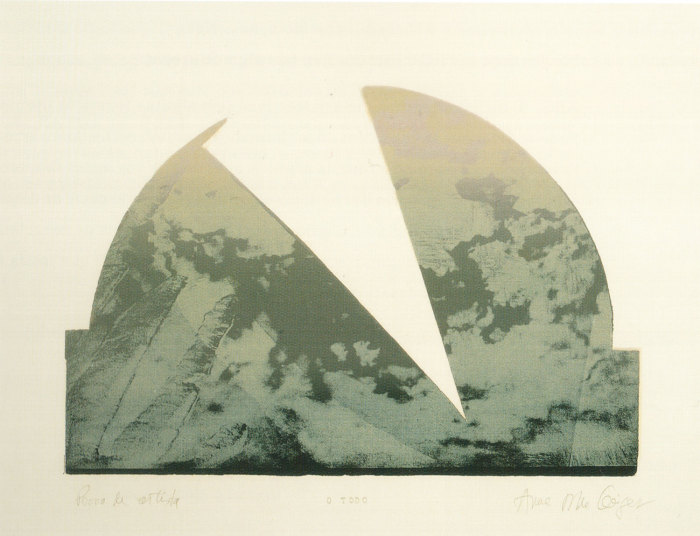

Anna Bella Geiger, O todo, 1974, photosilkscreen and metal, 58x72cm

DD: What is your relationship to feminism? As your notable series, Brasil Nativo/Brasil alienigena (1977) is now often read from this perspective.

ABG: People abroad were always a bit reluctant to show artists dealing with politics in Brazil, although at that time shows organizing Latin American artists and also female artists under a feminist label started. I mostly refused that kind of group show, because I often felt it was not relevant, that it was coming from some prejudice. I said yes once to a show of female video artists by an independent curator. There were German artists, and also Joan Jonas whose work I admired very much.

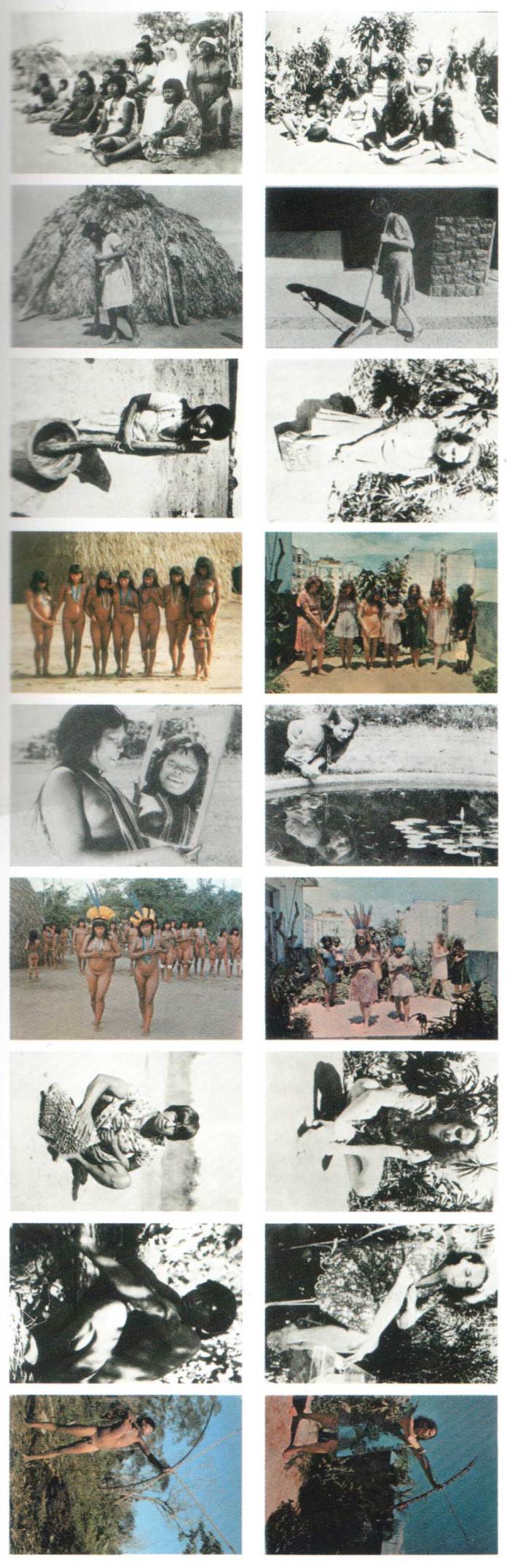

Anna Bella Geiger, Brasil Nativo/Brasil Alienígena, 1976/77, series of 18 postcards, photos by Luiz Carlos Velho, 10x15cm each

In the ’80s and ’90s, I read and taught about feminism. But I always thought these postcards were more simply the work of a Brazilian artist living in that difficult moment in which we were deprived of liberty, the right to vote, etc., more than a feminist approach. Some people saw an anti-colonialist position in that work, but to me it was more about drawing a relationship about the deprivation of democratic possibilities on a very simple level.

When I think about my whole career I often think of the acrobats that put these little dishes to turn on a stick, they have to add more so it keeps running or it will fall. That’s what I tried to do; I tried to keep renewing my ideas about what was happening.

Works courtesy of the artist and Mendes Wood, São Paulo.

Comments

There are no coments available.