11.01.2021

Artist and curator Christian Bendayán reviews a current of Amazonist art through the work of the artists Chonon Bensho, from the Shipibo-Konibo people, and Rember Yahuarcani, from the Áimen+ clan of the Huitoto-Murui people, who articulate ancestral knowledge to remember other forms of existence beyond the white logic that has deformed the territory known as Peru.

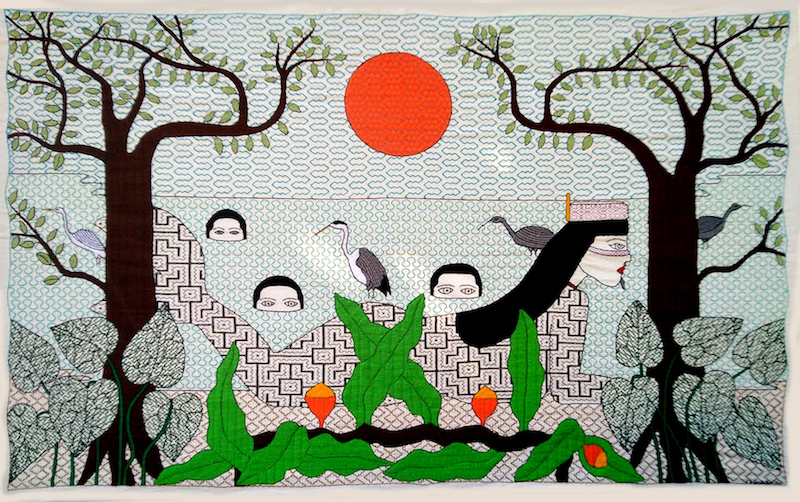

A current of Amazonian art is changing the way of seeing in Peru. Its source is the energy that is born among the Indigenous people of the Amazon, which gives form to stories that are usually transmitted orally, and which now, gives us a new perspective that allows us to see the protagonistic role humans, plants, animals, rivers, forests, skies, and mythic beings play in the destiny of the world.

The Amazonian art practice is aware of dangers that in they don’t warn us in the city about, such as the threat of ecocide and the loss of the spirits who have inhabited the Amazonian forests since time immemorial. In Peru, 48 Indigenous peoples remain, grouped into 17 linguistic families; they constitute the largest contribution of cultural diversity in Peru and they are full of knowledge, myths, stories, and visions that are fundamentally geared towards the survival of humanity. Artists like Chonon Bensho, of the Shipibo-Konibo nation, and Rember Yahuarcani of the Áimen+ clan of the Huitoto-Muri, create works that are distinctive for their creative processes and their intrinsic relationship with the forests and rivers, and above all spirits that guard them. It seems that climactic changes are causing the Amazon to overflow—and not only its waters, but also the energy of its people, who have protected their ancient knowledge; it has survived inclement nature and perpetual injustice and genocide, and today appears in Peru’s cities in the form of art, which is also the voice of the gods and mythical beings, who manifest themselves in order to help us to encounter our human, Indigenous, and spiritual essence. The following is a conversation with both artists that was produced in spaces that are very distinct and distant, physically speaking. The interview begins with Chonon Bensho, who corresponded with me from her home in the Indigenous community of Santa Clara, where he is preparing his first individual exhibition that will open in Lima at the beginning of 2021.

Chonon Bensho (CHB): I am an Indigenous woman, raised on love and the poetry of my ancestral language, surrounded by its affect and its lessons. At my birth, my mother buried her placenta in the ancestral land of the Santa Clara de Yarinacocha Native Community. This custom is performed to create an unbreakable bond between the newborn, the land, its family, the ancestors, and the spirits. I have done the same with my daughter Isa Biri, placing her umbilical cord in the roof of our house. Although not every member of the same Indigenous nation will always agree about everything, we have a shared cultural base, and this base is intimately tied to the land, to the plants, to memory, to affect. For us, the land is not a place without a soul and without a consciousness. Rather, every living thing is endowed with intelligence and a language.

CB: How important is the ancestral knowledge embodied in the kené (the name of a Shipibo-Konibo design) in our contemporary times?

CHB: We live in conversation with the elements of nature. Because of this, I believe that neither Indigenous people, nor Indigenous art, nor ancestral knowledge, nor the land exist as distinct entities. To sever ourselves from the land would be to lose our identity as people of a distinct nation with regard to the rest of society organized according to the idea of the nation-state. The land is our past, it is our present, and, if we would like to continue to be Shipibo-Konibo, it must also be our future. And I believe that the same can be said of all of humanity because human beings are part of nature: if we continue to destroy the environment, in the name of our greed, we will continue to become sick and dehumanized.

I believe that we, the Indigenous, and especially Indigenous women, are very sensitive to the voice of the land and of the invisible worlds, and have a special capacity to dream with the spirits.

CB: Despite having enrolled in the painting department of a school of fine arts, you chose to remain tied to the aesthetic and technical traditions of your people—the very reason why we are currently able to enjoy your rich work, an art that is generated from the love of creation, nature, and an ethics of respect for all beings. In what aspects of your work can your formal training in fine arts be found?

CHB: In addition to having the ability to cure, the ancient doctors were wise people who entered spiritual realities of great intensity in their dreams and visions. It is these realities that I am interested in portraying in my art. A luminous and vibrant beauty descends from the spirt worlds and fills our hearts with joy and elevates our thinking. The spirit beings are beautiful and kind-hearted, and they show us how to be like them, to act harmoniously and legitimately. I believe that the Amazonian land, as well as the other natural spaces, bears testament to the knowledge of God. And in this knowledge, there is a moving beauty. As an artist, and especially as an Indigenous creator, I believe my mission is to help manifest the spiritual beauty in our world, to contribute to the creation of beauty along with the Spirit of God in order to console its suffering, alleviate its pain, bring clarity, and elevate the heart of the people towards goodness, compassion, and affection.

CB: Unlike Chonon, the artist Rember Yahuarcani moved to Lima, the capital of Peru, almost two decades ago. He has not only made his presence be known through his exhibitions, but also through his contributions in many different conferences and publications. It has been a long time since he has worked in his studio located in the Plaza San Martín, the epicenter of civic participation in the political destiny of Peru, where the most influential massive protests have occurred. My questions begin with the great contrast in lifestyles, between his town in the Amazon and chaotic Lima. Rember, as an artist belonging to the Aimen+ clan, how do you experience the spirituality that you have inherited from your people, that which inhabits your paintings, in the reality of Lima?

CB: What do you say in the face of the injustices and abuses that Indigenous people continue to experience, of those whose voice seems not to matter simply because they live far away from the center of political power?

RY: My responsibility as an Indigenous person multiplies in front of a dirty and arrogant state. Currently, there are professional Indigenous people who have a lot of experience, and for this reason, I believe that in order to push through the mental and geographic block with regards to the Amazon, it is urgent that we include Indigenous professionals in all the different levels of government.

As an artist I am not disconnected from the activities of my people. The realization of a new house or the harvest of food are dynamics that allow me to experience the survival of my people first-hand.

CB: A little while ago, you visited your town and spent the health crisis quarantine there.

RY: Yes, last month, for example, my family prepared a new ranch. With axes and machetes in hand, we cleared the mountain together. Where I was working, I came across a big jergón, a deadly venomous snake. I reacted quickly before the animal could bite me and was able to kill it. It had been a long time since I had had an experience with the deadly part of the forest. Having the snake in my hands very much influenced the paintings I made after that—his form, color, movement, and the experience of being before death. The Amazon is not only a green space with great biodiversity and a tropical climate. It is its people, its dangers, its sadness, its scarcity, its extreme poverty, and its polluted rivers. I live with all of them and try to show the possibilities of the Indigenous world to create genuine work that has identity. I also live with its myths and stories, which are not static, but in constant movement. In the words of a fisherman or a hunter, the myth takes on another form and movement, like a great snake that slithers among the roots. The myth transforms itself into something real, alive, and transcendent that doesn’t die. In this dynamic, human is nature, and nature is human.

RY: They don’t understand the “humanity” of Indigenous society. They consider us inferiors, a second society with zero possibilities for managing our future. This perception is offensive and wrong. Let’s not forget that only 90 years ago, my ancestors were considered savages that needed to be civilized. The relationship the West has had with Indigenous societies is one of colossal arrogance: its sense of superiority is aberrant and unacceptable. If there aren’t substantial changes in society, the breech that the inequality and other evils that afflict us is opening up will be unsalvageable and will end in huge, convulsing social protests.

CB: What role do artistic practices play in changing this situation?

RY: In my view, artistic practices are the activity through which Indigenous society best develops itself. Some art galleries, museums, and curators see in our society a genuine art, of great sociocultural relevance with its own identity. But they don’t fool us. Many may believe that art made by Indigenous people is experiencing a privileged moment in the local art scene, but I still think that Indigenous artists are still considered inferior compared with whatever urban artist. This is because Indigenous creators have not partaken in equal measure in the city’s most “contemporary” spaces, those which officially decide what is and what is not “art.” For this very reason, it is urgent that Indigenous artists and their works gain access to commercial art galleries, contemporary art museums, and art fairs, and that they also achieve fair remuneration in the art market. However, we have been robbed of our voice by people tied to the extractivism in the Amazon, as well as cultural workers, designers, and artists, who have appropriated our knowledge without understanding that it is of vital importance that there be an authentic “collaboration” between Indigenous thinkers and academics in order to achieve a more just society.

Comments

There are no coments available.