01.08.2016

Alicia Herrero talks with curator Teresa Riccardi about the appropriation of the language of corporate capitalism in Herrero’s practice, used to denounce the oppressive role this exercises in the regulation of social life.

Teresa Riccardi: My first question has to do with research you’ve done in recent years. Could you tell us more about the work entitled Consideraciones sobre lo público: Un simposio en tres actos [Public Considerations, a Symposium in Three Acts] and the upcoming “staging” you’ll make of the project in Montevideo?

Alicia Herrero: The work posits exploring if the arena in which there have been gains in public rights on the global level can have anything to do with these forums’ normalized language-and action-related behaviors. Or how these devices’ diagrams, structures and timing regulate democracy’s language, actions and forms to impose a performative condition. As such, it could be the case that if we take up these events both critically and conventionally, subject them to de-regulation, alter their structure and propose another kind of performativity for them, it might favor the appearance of rhythms capable of going further and at some point affecting the production of commonplace demands. It’s a long-term project.

Consideraciones sobre lo público. Un simposio en tres actos (CSP; 2010) extends a path for work and research that began with Magazine in situ–(MIS; 2004) and Links (2007). To different degrees, the three projects explore the creation of situations that are mediated by protocols and conventions that arise from round-table discussions, debates and conferences as well as their temporal logic, their location and the stakeholders that constitute them (MIS); their ways of speaking and acting in public (Links). CSP takes up the performative dimension of a public policy symposium elaborated by means of the knowledge-economy-legality triad. Its actions emerged from specific public spaces in Buenos Aires: the University of Buenos Aires’s auditorium, its counterpart at Argentina’s central bank and the auditorium at the National Congress. Over the course of its three acts, the force dynamics CSP articulates progressively distorted the “symposium” template, shaking up hierarchies to allow other sensible forces, new rules, platforms, parliamentary procedures, social agents from varying sectors, scripted actors and musicians, alongside a never-before-seen visual-instrumental complex, to be added. These dimensions quite naturally behave with a theatricality that is proper to any auditorium, congress of experts, political convention, etc., with all their artifice, signature rhetoric, the degrees to which they emphasize or attenuate the rigidity of bodies present within the space, their obedient behavior, what is heard, certain voices’ sovereign authority and others’ silences, repeated gestures and the words of the community there gathered.

A new edition of CSP will be held in Montevideo, in 2016, at which time it will seek to go deeper into issues and formal strategies the previous session’s last act took up, yet at bottom seeks to incorporate other situations given the current political juncture, the city and the venues at which it will take place. Each act’s audiovisual materials and publications will allow us to follow the development of changes that are constantly in progress and that by means of these changes integrate other interactive contexts such as exhibitions, new publications or classes.

TR: What role do language and the performative dimension play in your work?

AH: I work with language’s materiality, its existence in space and in bodies, in the gravity of language. I question language as a constructor of cultural phenomena, of realities. The ways language constructs subjectivity and normative behaviors, with their canon of patriarchal authority; its ostentatious display of knowledge hierarchies; the disciplined collective body’s performance in public institutions; the institutional rhetoric of politics and art; the “sexy” language marketing uses. All the ways language is acted upon and all the ways language acts on forms.

Working with devices through which our words and discourses are made public, like CSP, means operating with their performative materiality—their enactment. This allows making evident their rules, meaning-production and acts of monitoring. I work with that material and I look to see what possible forms of intervention may be there. The exercise of their transformation is always a political exercise and for that reason a construction of subjectivity. It opens, reveals a public condition, smashes concepts that smother invention, operates on words, acts and the use of space. I’m drawn to that instant in which certain images that these operations produce reveal new places of enunciation, or when the conscious routine of performativity in a public allocution (so-called performative talks) offers the ability to act on those genres and, in that way, change them. It lets you shake off the tyranny of the always-same, collapse the anachronic and the monolithic. “Out-of-norm” language and actions are threatening to the machine. That place is moving to me and it’s there that I like to reside—it’s where I hear my heart beat.

TR: In your artistic practice we often confront a series of problems or issues (be they politics, legal matters, economics or language) that are connected in some diagrammatic way. Can you take us through this process at different moments in your artistic practice? When do they appear for the first time?

AH: Not-very-transparent systems like finance, the economy or the art market; the limits of legal constructions or institutional simulacra are indeed some of the issues I take on. How do I get from art to some distant place, without any guide since no one went there before? I try to put art in a new situation and perceive the instant in which it is produced. By introducing abstruse constructions into bureaucratic systems, the investigative path demands dynamic forms of connection, illustrations that could be called diagrams. They document the intimate moments of this process, allow for synthesis, rule reinvention, ways of reordering. As such, something within this beginning affects other phases of the work. Sometimes the diagrams bring together different phases or parts that make up a project, deploy their visual grammars, their objects; at other times they work as instructions. I also recur to these sorts of illustrations to compose layers of relationships between projects and how they affect one another. Therefore, the illustrations shed light on different formal and/or thematic “persistences” and this reaffirms work concepts, challenges for radicalizing problems and technologies. Concentrating time, visualizing meanings that overlap, dissolving linearity, making up its own rules.

When did they emerge? They might be derived from long series from the 1990s, which involved me in inventories of everyday things and closed gender-control systems, but I also can think of diagrams that appear, with complex layers, in the project entitled Chat (2001) at the Boijmans Museum in Rotterdam.

TR: How do you refer to the art world in works like Fe de Erratas or Action’ Instrument Box?

In Argentina in the 90s, free trade policy deepened its roots and this led to an exaggerated correlation within the art world. Fairs start springing up, new foundations, collector-founded museums start to constitute a new cultural landscape; an industry coalesces. Back then, the naturalized relationship between the avant-garde, metaphysics and money struck me as a construction that was as problematic as it was unspoken and as such, something of interest, worth taking on from some possible place at a time when everything seemed oriented toward a sole paradigm. It was from there that the Fe de Erratas series emerged alongside the method first used in 1998 for the exhibition I did in Buenos Aires at the Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericano entitled Un paisaje hechizado.

This work, which applied that method, proposes an exercise of approach to the phenomenon of this historic relationship and does so using real economic data. Clearly, the question has to do with the “impact” the market exerts over perception, the image we have of art and on effects the artworks themselves contain. Fe de Erratas develops through a process inspired by market indicators, a proviso, a fe de erratas (i.e., a published and acknowledged correction) corresponding to the economic information in art auction house catalogues like Sotheby’s and Christie’s, with an interest in giving visual life to the abstraction of a price. This is done through creating a canon I propose that comes out of a system of calculations and correspondences between dollars and centimeters, and which graphically validates sales prices in centimeters on top of photos of the sold artworks. This produces an expansion or contraction of the artwork ‘s horizontal coordinate to the degree that the number of zeroes in the price increases or decreases.

With expanded internet research, I detect that at the same time as the 2008 global economic collapse, one can see an all-time high-point in prices and sales unlike any other in the history of the Fine Arts. Add to this a proliferation of HNWI and ultra-HNWI (i.e., “high-net-worth individual”) collectors in contemporary art. The entire phenomenon becomes the theme of Fe de Erratas.

As part of the creation of a fictitious consulting company named Auctions, Market & Money (2008), which I define as “the first imagination-and-research-based consultancy for investigating the impact that the market, money and exchange exert over our perceptions of art,” I begin research on all contemporary art sales in both galleries throughout 2008. I elaborate a lexicon, complex calculations and I create new concepts and instruments appropriate to the object I seek to question. Indicator graphics, slides, files, new catalogue pages and measuring instruments are added to the series. That is how Fe de Erratas re-posits its object of inquiry and exposes what sorts of rules are revealed as part of the exercise.

In 2012, using the same editorial and design protocols as a Sotheby’s catalogue, I produced a contemporary art Fe de erratas-catálogo that represented different price behaviors in 2008. The catalogue offers a description of the procedures and instruments used, and shows how achieved price variables compress the artworks’ images or, conversely, expand them, notably affecting some pages’ width. When gathering these variables and the relationships among them, it is prices that produce the visual event.

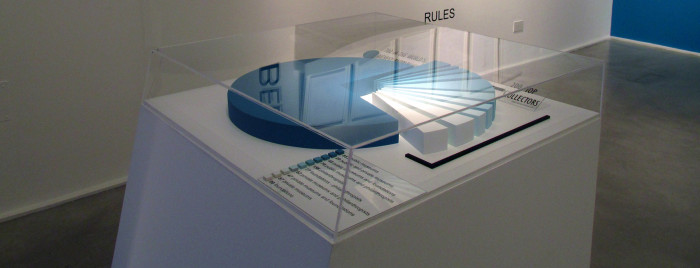

In 2010 and 2011 I put together ten different graphic pieces that were the outcomes of the Fe de Erratas method in the multi-piece Action-Instruments Box (2010). The set was conceived of as an artwork that would critically stage an intervention into art-market circuits and gathered “EPIPHENOMENA-EVIDENCE-REVELATIONS-BELIEFS” as proof and argumentation for a critical and legal judgment on current art market rules. The piece is activated by a PR woman from the Auctions, Market & Money consultancy who wears a TV-style sales uniform that matches the object’s colors. As if they were instructions, she describes each of the graphic elements and calls on the audience—do-it-yourself style—to apply the methodology to look at other periods and come up with even more arguments. The performance posits and questions the lack of a sense of jurisprudence when it comes to issues of art, economy and rights.

Installation view of Saul Robbins’ How Can I Help? - An Artful Dialogue at Pelican Bomb Gallery X, New Orleans. Courtesy the artist and Pelican Bomb, New Orleans. Photo by Jonathan Traviesa.

TR: In what way do fiction and reality operate in artworks such as El Museo de la Economía Política del Arte or Mundus Financial Corporation Inc. Evidencia?

AH: The Museo de la Economía Política del Arte (MEPA; 2012) fermented a borderline action zone. It was a virtual museum that produced reality using the power that statistical language and its formal strategies exert. MEPA emerges as a possible forum to gather and articulate a series of longstanding practices that take art’s political economy as their core. But by moving through a period in which museums expand their attributes and missions at the same time the political economy increasingly intrudes into the art realm, MEPA ends up existing amid conditions that fluctuate between the virtual and the real. The artworks that make it up provide real, verifiable data and some of the pieces are presented alongside prolix notaries’ certifications that legalize data and source veracity. At the same time, the work has become a receptor for documents from from a variety of global art-related political economy episodes that it safeguards by means of an archive.

One of the artworks the piece includes is Plus-Valía (2012), composed of graphic elements that portray percentages, relationships and predominance on the part of a group of two hundred art-world collectors. It was elaborated based on cross-referencing information Forbes magazine published on the world’s seven hundred richest individuals against information in ArtNews on art’s “top-200” collectors. The ranked set of 200 eminent collectors is included in the world’s seven hundred richest. Plus-Valía indicates what percentage of the cited collectors control foundations or personal museums, play philanthropic roles in educational, research or university centers or sit on public museum or biennial boards—or play all these roles simultaneously. It reveals the economy’s contextual rings, private intervention into the public sphere and the formation of decision-making, taste and power conglomerates in that arena. It also makes evident not only the global subordination of cultural policy but as well that of public education projects increasingly subject to the dominion of capital flow, something we have witnessed silently for a long time as part of a global-scale “systemic model.”

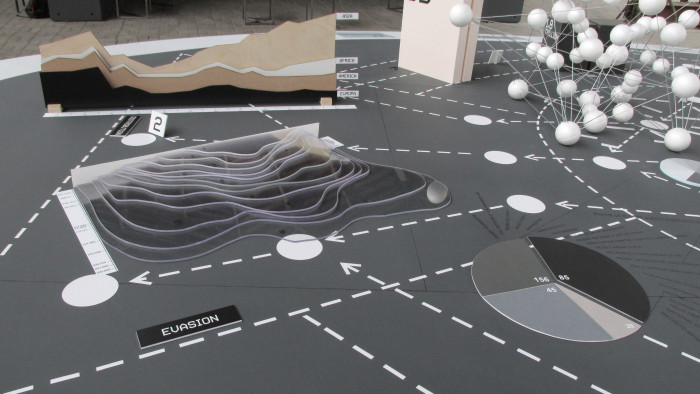

In Mundus Financial Corporation Inc. Evidencia (MFCIE; 2015) I posit an approach to the global-interaction regime of political economy and the finance industry, wherein an arts chapter can also be found. The work centers on how hard it is to perceive the language of economics and its systematic importance. It deploys a strategy to skip over certain perception-related policies that tend to hide capital’s supra-power over world control by making images volatile, spreading information or dissipating illegal actions. The procedure starts off with an articulation of verifiable and transcendent data which are staged and presented as evidence. It concentrates interest in economic architectures and camouflage strategies.

Installation view of Tatyana Fazlalizadeh’s A Solace with My Mama, 2017, at Pelican Bomb Gallery X, New Orleans. Six graphite-on-paper drawings and an audio file. Courtesy the artist and Pelican Bomb, New Orleans. Photo by Jonathan Traviesa.

Dioramas that emerged in the nineteenth century as new visual technologies proposed domestic options that were placed before other types of much more massive “spectacles” of perception. This perceptual quality intrigued me as a way to rehearse global financial architecture scenes while even considering their virtues in relation to the spread of scientific knowledge. MFCIE’s display can only be appreciated by means of 360-degree, long-sequence takes or from a vertical viewpoint. It presents two scenes, one that plays out at the base, and another, hidden scene audiences can deploy. Above and below the algorithm of the 147-corporation conglomerate that controls the greatest percentage of global capital flow, forms resolved using architectural materials and printed images, the outcome of both macro- and micro-economic as well as historical research, expand. They materialize knowledge on tax evasion, inequality, capital’s power within art and in universities, global wealth distribution estimates up to the year 3000, the relationships between coups d’état and corporations, etc. The work stages values, the magnitude of the phenomenon and catastrophe and therefore posits the possibility of conferring “evidence” status on the diorama. Obviously the work puts forth an odd epistemological dimension that is certainly questionable from a legal perspective; nevertheless, it does not cease to be testimony, a public declaration that at least for now “has no legal standing.”

Comments

There are no coments available.