23.03.2015

Ericka Flórez analyzes the relation between the representation of terror in the Gótico Tropical movies—produced by Luis Ospina and Carlos Mayolo in the 1970s and ‘80s in Cali, Colombia—and the persistence of pre-modern beliefs and cosmogonies in the local popular imagination.

I PUT A SPELL ON SPACE: Torrid-Zone Myths and Economy

Here heat is not the languor that the land prepares for a dramatic plot. More precisely it is the figure for an atmosphere in which natural and political history are united in what can still be called Cold War.

Michael Taussig, My Cocaine Museum (2)

1. SUN AND HAPPINESS

I wondered why stories of paradise always come with a hint of the ominous. I wondered why a city with this kind of light:

characterized by this:

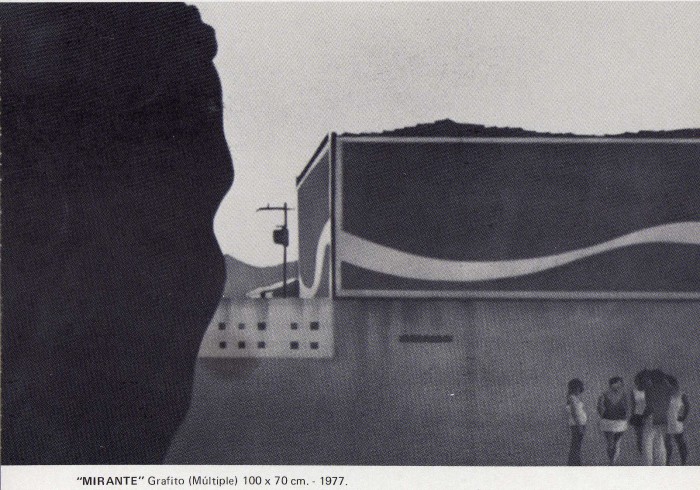

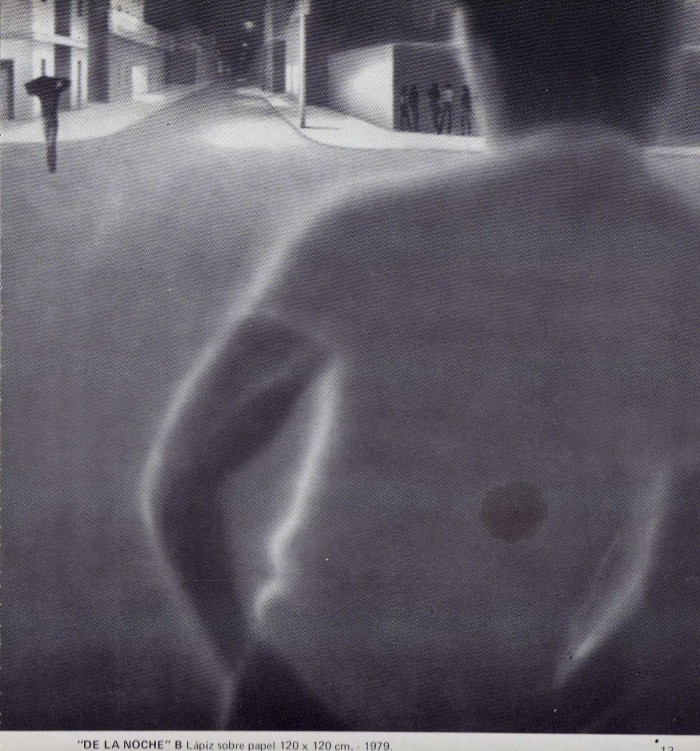

and this:

…why artists in a city with those characteristics produce images where darkness is the protagonist:

…and zombie, vampire and ghost pictures:

El Gótico Tropical (i.e., Tropical Goth) was an artistic experiment that took place in Cali, Colombia in and around the 1980s and that sought to materialize an apparent contradiction: if the horror genre, both in film and literature, had originated in Nordic countries, then what would torrid-zone terror be? The question that Colombian writer Álvaro Mutis first asked was taken up by Cali-based filmmakers Carlos Mayolo and Luis Ospina. They created a series of films that lent form to that kind of terror and that rescue local myths belonging to a rural cosmogony.

In the present essay I hope to point out the importance of reclaiming that cosmogony, beyond its folkloric value; I attempt to speculate regarding the origin of the link between this sunny city and darkness as well as hidden forces; and ultimately I seek echoes of the Tropical Goth in work by artists from younger generations like Ana María Millán and Giovanni Vargas. These questions have been empowered by work from Michael Taussig, an Australian anthropologist who studies the relationship between mythology and economy in the Cauca Valley, the Colombian region where the films and artworks I will place into relationship were produced. Many of Taussig’s theories seem like the (not so) academic correlate of what these artists have done in fiction. Thus the present text works as a parallel between his and the artists’ work.

Cali is a city marked by a subtle yet persistent fatality. The image that has been constructed atop it, based on an “exoticizing” gaze, is that of a tropical paradise that is home to a je ne sais quoi that encourages vice and excess. A city where most of the women are buxom and exuberant; in which dancing and revelry are central to family, social and economic life. A city that is birthplace and headquarters to some of the world’s most important drug cartels and in which, therefore, drugs are absurdly cheap and available.

It could be said Cali is a “black city with a great many whites”, or that it is the planet’s number-two white city with the highest black population (partly a result of historic African migrations that came to work the sugarcane plantations as well as migration on the part of Pacific coast residents). People here are uncomplicated, extroverted and much more given to strolling the streets than staying indoors. The weather, with its mix of heat and breeze, rounds out the vacation resort feel. And though there is no ocean, Cali almost seems a seaside town, maybe because the people maintain a notably close relationship to local rivers, emblematic spots for working-class family fun—and for teens to start using drugs. The climate, the connection to dance, the yen for outdoor sociability and the black heritage mean that the body and sensuality take a central place in local social and public life.

These are some of the characteristics that make up the city’s complexity and particularity. This description is an image of the city, that, like every caricature, no matter how exaggerated and partial, contains some element of truth. Because of its propensity to vice, excess, corruption, drug trafficking and the impossibility of any progress, it has always been said that dark forces govern Cali.

2. A CITY RUN BY THE DEVIL

They say the devil is stuck in Cali. Centuries ago a legend arose recounting that the devil came to the city and that to get him out, inhabitants erected three crosses at the crest of one of its guardian peaks. The measure, rather than spooking the fiend, trapped him there forever. It explains the local tendency to both produce evil and be its victim.

Since it has featured in a number of film productions, you could say this myth has become an obsession for artists, filmmakers and city residents in general. For instance, it’s said that one of the Cali soccer teams prays to the devil, uses his image as a logo and that fans pay homage to him through chants and fanzines. They also say there is a curse on the city of Cali that prevents the ‘América’ team from wining the Copa Libertadores championship.” (3)

3. VAMPIRES IN BROAD DAYLIGHT

In Tropical Goth films like Pura sangre (Luis Ospina, 1982) or Carne de tu carne (Carlos Mayolo, 1983) the figures of the vampire and the zombie are used to represent historic power relations between rich sugar hacienda owners and their peasants.

The main plot element in Pura sangre is a hacienda owner on his deathbed in a hospital who requires human blood for survival. A criminal gang works for him, kidnapping children off the streets, draining their blood and bringing it to their boss. To explain away the serial disappearances, the populace creates the legend of the monstruo de los mangones—“the vacant-lot monster”—a real and highly popular legend that several generations of Cali children grew up with. It was a monster who kidnapped, abused and raped children. While throughout the film, we see that it is the rich who are guilty of the serial disappearances, the press accuses a black, likely homeless man of being the monstruo de los mangones:

Carne de tu carne tells the story of two teenagers who are heirs to family-owned lands. At the end of the film, the two young people turn into vampire-zombies that start to attack anything that comes near (in this case the peasants that work on their property). The teens’ parents and relatives are unaware of what’s happening and are ignorant of the fact that their own children cause the plot’s destructive onslaught.

Though in Carne de tu carne and Pura sangre the place of victim and victimizer appear stable (the poor and working class are victims, the rich the oppressors), perhaps its charm resides in the opposite. More than a one-sided condemnation of who is poor and who is a victimizer, these films constantly cast doubt as to who is able to determine what is or is not real and, as such, who holds power.

The rich scoff at superstitions, at poor folks’ and peasants’ imaginations (their belief in monsters, vampires and ghosts) yet it is the rich who embody these figures in the films. It is they who evolve into monsters or vampires. Thus the rich become what the poor imagine them to be. Who wields power in such a situation? Who imagined whom? Who gave life to whom? Who has the power to decide what is real? The limits between magic and reality, between the official and the underground stories, are foregrounded and when that division is blurred, the notion that control always resides on one side is called into question.

Monolithic visions of power always evince fissures, pauses and instances of imbalance. Along these lines, Michael Taussig recounts an anecdote (4) in which wealthy landowners used to think that any ill that befell them was caused by spells the slaves that worked their fields, and who held an animist cosmogony, placed upon them. As a result, they would recur to the indigenous population since the latter were the only ones who knew how to lift such curses. The story sheds light on the ways in which another time’s beliefs (belonging to another worldview, born in another economic system) can—at least momentarily, hypothetically and metaphorically—cause the kind of power and the kind of knowledge that capitalism produces to waver. Taussig’s writings, like Tropical Goth films, signal the persistence of a past that resists annihilation and nullification at the hands of a new economic system and the worldview it imposes (5).

Thus the films of the Tropical Goth share with the Brazilian anthropophagic movement (6) the task of pointing out the ambiguity of power, of complicating conflict further, as well as a need to disassemble the binary vision of victim and victimizer before taking up any examination of miscegenation or colonization.

4. FREEZING SUSPENSE

In succeeding generations, what is taken from the Tropical Goth is not so much an interest in looking at power relations through the figures of the vampire, the zombie and ghosts. Instead of fashioning narratives that feature a beginning, a conflict and a dénouement, what younger artists have taken up is the creation of atmospheres in which a “stagnation” of suspense prevails; environments where there is a promise that something is about to arrive on the scene but that never does. These are misty environments, lit amid shadows as seen above in the images of 1970s-era artists like Ever Astudillo, Oscar Muñoz and Fernell Franco.

In the series Vengo por tu espalda (1998), Ana María Millán gathers horror movie stills in which a woman is about to be attacked from behind; so the dénouement of the narrative disappears from the image. Rather, this suspense moment is frozen, never to develop further, as is also the case in videos by Giovanni Vargas.

Understanding Giovanni Vargas’s La oscuridad no miente (2008) as a sort of portrait of Cali led me to ponder up to what extent this suspense-freezing mechanism was an analogous narrative structure to the city’s history in the 1990s, a time when life meant always feeling that the worst was just about to happen even as a full dénouement never presented itself. This was precisely how drug trafficking existed among us: as an underground terror, as an imminent crisis that never ended in a grand catastrophe but rather had to be lived through as a sort of naturalized fear and distrust. It gradually created scar tissue, a nick in the unconscious of the generations that grew up beside that “dark presence.”

5. THE POWER OF THE INANIMATE

A large part of Ana María Millán’s practice is concerned with dismantling the tricks that horror deploys to set up special effects with precarious production means. One of her pieces analyzes the tricks some of those films have used to endow inanimate objects with life, in order to understand its mechanism.

Thus it seems Ana María Millán’s interest might be a sort of reverse-animism centered not on animating objects by means of the intrinsic power they may contain but rather in their dependence on an agent for activation, an agent whose efforts will always be clumsy, risible and faulty.

6. A NEW/OLD THEORY OF CAUSALITY

In terror, the causes behind what happens are always attributable to supernatural considerations, impossible to explain within the Western cognitive systems. What’s interesting about this way of explaining things is the place it affords the subject.

In La mansión de Araucaima (Carlos Mayolo, 1986) a number of complications are interwoven between the main characters, that end in inexplicable tragedy or that only can be explained by a spell on the house where they live. Immediately following the film’s climax (the female protagonist’s suicide), we see a wide take of this house, as if it were the explanation of what has occurred.

At the end of the picture something is undone as the characters abandon the hacienda. All—not merely the character of the slave—appear to have been liberated from some yoke or shackle that was determining their destiny and constituting the space itself.

According to Mayolo, one of the Tropical Goth’s principal characteristics is the force that its spaces wield as well as the character-like, leading role they take on—particularly the figure of the house, that “becomes a power-center to which instinct and innocence arrive for their destruction”(7). Therefore, in accord with the artistic movement’s logic, the subjects enclosed within situations do not hold the blame for anything that happens; they are not agents, but rather victims relegated to irredeemable damnation that is intrinsic to the place where they live.

Explaining causalities based on the supernatural forms part of a cosmogony that developed in a pre-capitalist era when the notion of the subject did not exist. In contexts in which objects, the inanimate, myth and legend are endowed with powers, the subject is de-centered, loses its power and is left to the mercy of that which surrounds it.

It is specifically here that Taussig’s ideas help dimension the critical potential of everything that artist-filmmakers like Mayolo, Ospina, Millán and Vargas end up foregrounding. The anthropologist’s studies underline the power of what the artists have reclaimed: a constellation of beliefs and manifestations that otherwise might be thought of as anodyne or merely folkloric.

By analyzing the relationship between Cauca Valley hacienda-owners and laborers, Taussig studies the confrontation between two cosmogonies, each a product of a different economic system—one capitalist (based on a reification of time, subjects and objects), the other pre-capitalist.

Capitalism (i.e., commodity fetishism), as Taussig points out, makes the process by which an object was constructed (the time and means that someone devoted to its production) invisible, or put another way, eliminates its “human” dimension. In the pre-capitalist economy this does not occur since the product is associated with the process that brings about its existence. In such a system, the object is always the product of a relationship among individuals and its existence is not taken for granted. In the same way, modern science proposes a subject-object relationship in which the former exerts absolute power. Based on that epistemology, the subject is never affected by the object and therefore objectivity is possible, thus paving the way for assuming a sole version of “Reality”- and all the catastrophic consequences this entails.

In a culture where everything is exploitable—a culture that makes us assume that reality is a defined, static object—an attempt to reclaim the animist worldview as well as belief in the supernatural takes relevance. What Taussig and these artists’ and filmmakers’ productions underline is that these worldviews still exert an effect, remain with us in an underground fashion, offering evidence that not everything can be explained and that there are things that lie beyond our control.

Starting decades ago, the social sciences have sought to integrate into their paradigms this vision of the subject not as an inert-object administrator that observes unaffected from a distance, but rather, as an agent immersed within what it observes. That thinking, now very much in vogue, which would have us remember that “what we see looks at us,” was with us all along.

7. DARK FORCES

Cali has a special relationship with evil and Taussig explains it through the connection that the region has with gold and cocaine. This association with the devil is no simple anecdote, myth or local quirk.

The relationship between sugarcane plantation workers and the devil was explored in depth in The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America (8). Taussig analyzes the workers’ deal with the devil as a way to cut more sugarcane without expending additional effort and therefore earn a higher daily wage. However, the extra money could be used for nothing other than vices, excess and luxuries. When it went toward something productive, like a hog to be fattened and subsequently sold, the animal would die or lose weight. In the same way, if there were a worker subject to the pact, the plot he was working would dry up and no more sugarcane would grow. Taussig also describes the link between diabolical covenants and self-destruction. Almost everyone who made the deal suffered a dramatic, absurd end, (e.g., the man who chokes to death on his dentures).

For Taussig, the plantation slaves’ animist logic “not only reveals the past but the present order of things;” (9) and also underlines reifications that capitalism produces as well as its linear, acquisitive logic.

A deal with the devil forms part of a cosmogony more based on spending than on production in a culture that is stuck in an possibility for advancement, centered on a perennial and vicious cycle of excess. Sugarcane plantation laborers and gold-miners in Timbiquí (10) that entered into such pacts became rich but suffered horrifying ends, as did the regions where those mines and plantations were situated. The inhabitants of Timbiquí say God gave gold to the devil as his share of the world (11); Taussig seeks to show that first it was gold, then cocaine, but the logic remains the same: these elements are dark matter that can take any form; their versatility, as well as their relationship to wealth, generate brutality among men. It is the logical pre-history to drug trafficking: an excess that goes nowhere, a bonanza that leads only to self-destruction.

The Tropical Goth as well as work by Ana María Millán and Giovanni Vargas recount the experience of living in an accursed space (damned by the devil, by monoculture, by witchcraft, by the past, by drug trafficking or by whatever else) while updating a narrative structure of entrapment, that of a people condemned to the vicious cycle of false riches. A people bound to the curse of the space they inhabit.

8. THE PAST AND ITS GHOSTLY CHARACTER

The main feature of artists’, filmmakers’ and writers’ 1970s-era production in Cali (Andrés Caicedo, Luis Ospina, Carlos Mayolo, Ever Astudillo, Fernell Francom and Óscar Muñoz, among others) observes and contemplates the modern transition from the rural to the urban and the traumatic nature of the process.

Zombies, vampires and ghosts occupy a gray, intermediate zone, neither dead nor alive yet simultaneously both. In our cognitive system—that tends to think in binary terms—it is an impossible-to-categorize form of existence and perhaps this is what lends it its ominous character. Derrida said the past exists among us in a spectral fashion. The past, and ghosts, are undefined forms of existence, dark presences that operate from a place of invisibility and that represent transitional states of being.

The ominous, the supernatural and the spectral in these works is used to represent states as transitional as the presence of the rural among us or the light that produces the shadows that Ever, Óscar and Fernell sought to capture in their images, perhaps to speak of all that darkness that slips in among so much sunlight—a thriller with people who dance amid the cane-fields.

Cali Choreography Dancing Show, Ana María Millán y Mónica Restrepo, 2008

Notes

(1) All videos presented in this article are downloaded from the web. Each fragment is selected and reconfigured into a new clip showing the most relevant of each work according to the argument that it accompanies.

(2) Michael Taussig. Mi museo de la cocaína. Editorial Universidad del Cauca, 2013, p. 59. NOTE: Translator’s rendition of Flórez’s Spanish-language Taussig citation.

(3) Ana María Millán, in Happy Days, a publication by Juan Mejía. Galería Valenzuela y Klenner. La Silueta Ediciones, Bogotá 2009.

(4) Interview with Michael Taussig on the program entitled ConversanDos: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NCmoGha1e4c.

(5) It is quite odd that Taussig appears to be unaware of Mayolo and Ospina, two other thinker/narrators of the myth-economy relationship in the Cauca Valley, when their work was so similar. Taussig’s writings are the theoretical counterpoint to what the filmmakers achieve narratively in the tropical gothic. This seems even stranger when we remember the anthropologist published his book The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America for the first time in 1980, the same decade in which all the Tropical Gothic pictures were released, and even odder when we observe that the entire body of Taussig’s work is per se a questioning of anthropology’s wonted epistemology, and that it advocates on behalf of “documentary forms that overlap with fiction,” what the anthropologist has called ficto-criticism. Only forms such as those, or literary language, says Taussig in the preface to The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America, “will be able to understand how ideas work emotionally and how they construct an image of the world based on the way in which these are put into words, into language.” How might Taussig’s studies have changed if he had known Ospina and Mayolo’s films? Might have Ospina and Mayolo been familiar with Taussig and provided the anthropologist with a literary and fictional support for the notions he studied? [NOTE: The preceding quote is the translator’s rendition of Flórez’s Spanish-language Taussig citation.]

(6) See more on this idea in Michel Faguet’s text “How Not to Make a Documentary Film”

http://www.afterall.org/journal/issue.21/pornomiseria.or.how.not.make.documentary.film

(7) http://www.lugaradudas.org/publicaciones/01_carlos_mayolo.pdf

(8) Michael Taussig, The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America. University of North Carolina Press, 1980 (thirtieth anniversary edition, 2010). NOTE: Translator’s rendition of Flórez’s Spanish-language Taussig citation.

(9) The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America, p. 229. NOTE: Translator’s rendition of Flórez’s Spanish-language Taussig citation.

(10) An area near Cali and a center of the mining industry.

(11) Michael Taussig. My Cocaine Museum. Editorial Universidad del Cauca, 2013

Comments

There are no coments available.