14.09.2015

Kelman Duran reflects on the media representation of racial and sexual diversity and immigration conflicts in the US, and the issues of “cultural translation” that arise.

In the West we have seen a recourse back to ethno-nationalism, and specifically in Europe and in America, “race riots” fueled by capitalist depression. The symbols of Mike Brown, Freddie Gray, and countless other Black women, men, trans, and queer people have become metonyms for the failures of democracy, as packaged and touted by U.S. imperialism. How does media translate these bodies (dead or alive)? What is the language of translation, since information is indeed filtered by our consciousness, and then placed in a domain that we will either anguish over and critically wade through or un-empathically sift to the side?

When thinking about black and brown consciousness and the value of experience, we must take into account how the canon of humanities, which has given us an aesthetic education, constantly fails to consider the way it translates the wants of marginal populations. A quote by Dipesh Chakrabarty, who is part of the Subaltern Studies group, in relation to “peasant” political consciousness in India might give us insight into how media renders black consciousness, specifically in relation to the protesters in Ferguson. Chakrabarty explains Guha’s notion of how the territories of political consciousness in peasant uprisings cannot be successfully rendered through European analytical parameters. Also, that these uprisings, these collective actions in colonial India “stretched the imaginary boundaries of the category ‘political’ far beyond the territories assigned to it in European political thought.”(1) These same parameters characterize “peasant” consciousness as “pre-political,” which would point to a denial of the collective and conceptual framework used by this population to make claims to their owners. Naming the protesters as thugs and looters denies the protesters a consciousness. The rage attributed to the looting was assigned a criminal character and not a political or aesthetic one. It is in the naming that the humanities gives itself the power to report.

Hito Steyerl in The Language of Things writes, “according to Benjamin, this language of things is mute, it is magical and its medium is material community. Therefore, we have to assume that there is a language of stones, pans and cardboard boxes. Lamps speak as if inhabited by spirits. Mountains and foxes are involved in discourse. High-rise buildings chat with each other. Paintings gossip.”(2) It is worth noting that these commodities, these “stones, pans and cardboard boxes,”(3) are also filtered as commodities through capital, incorporation being one of the mediums through which capital translates. If we follow Benjamin’s logic we can maybe say that the descriptive mediums through which capital operates take away the magic of things, of bodies, and of protesters, that is if we can irrationally allow ourselves to conflate magic and consciousness.

Gayatri Spivak, another member of the Subaltern Studies group writes, “every definition or description of culture comes from the cultural assumptions of the investigator. Euro-U.S. academic culture, shared, with appropriate differences, by elite academic culture everywhere, is so widespread and powerful that it is thought of as transparent and capable of reporting on all cultures.”(4) I also would add: reporting on things, because the act of naming is the act of translating, and translation within the media supercomplex and contemporary historiography happens symmetrically; symmetry reflecting reason and rationality as well linearity, due to its descriptive power usually only flowing from the top down. A review by Brian Droitcour in Art in America of Kenneth Goldsmith’s performance in which he read/performed Mike Brown’s autopsy reveals this type of description stepped in linearity. Droitcour states that “Goldsmith didn’t pretend to feel what Michael Brown felt, or use his body as a proxy. Instead, he occupied the position of the medical examiner, giving his body to the autopsy’s anonymous, institutional words.”(5) It is always a problem when one resurrects the dead from an institutional position. The form as well the content that Goldsmith chose to perform are a type of “cognitive failure,” a notion Spivak uses to reveal positionality. She states that “the sophisticated vocabulary of much contemporary historiography successfully shields this cognitive failure, and this success-in failure, this sanctioned ignorance is inseparable from colonial domination.”(6) For this particular performance the sanction was provided by a Brown University, assuming they knew what was going to be performed ahead of time.

We can also see this cognitive failure if we read Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson’s grand jury testimony and his description of Mike Brown, the unarmed teenager he murdered. Wilson wrote, “When I grabbed him the only way I can describe it is I felt like a 5-year-old holding onto Hulk Hogan.”(7) Obviously, this is how the police-state thinks; however, a number of a studies done about the way whites super-humanize blacks by the journal of Social Psychology and Personality Science conclude that “ […] the super-humanization of Blacks predicts denial of pain to Black versus White targets. Together, these studies demonstrate a novel and potentially detrimental process through which Whites perceive Blacks.(8) The black “thing” not fully able to feel pain the way his white counterpart does, and as we will see later, the Jordanian artist not fully human.

One would think that after “March Madness” (as the hip hop artist Future calls it), the violent killings of unarmed black men and women, and trans people would decline – March of 2015 being the month where police killed more than 100 people.(9) However, this is precisely the false idea that democracy teaches us: the idea of progress, and as Spivak assumes, one should not be “convinced that the story of human movement to a greater control of the public sphere is necessarily a story of progress.”(10) In that sense, Franco Bifo Berardi even suggests that maybe what we need is degrowth.(11)

Spivak, in relation to arts, states with complicity: “that literature and the arts can support an advanced nationalism is no secret.”(12) An example of how art parallels state interests is an archived film by the British Movietone Archive of an artist exhibiting work to a Jordanian prince in London.(13) The most interesting variable is not how they created this narrative around this exhibition opening, but the actual naming of the clip, which is titled “Jordanian Girl Artist.” The artist is first classified by nationality, and then as a girl, not even a woman. The birth name and the practice, is of no importance, invisible to the larger institution. “Jordanian girl” shows us how we give ourselves the right to gender an artist. More so, if it was a white body, let us pretend, a British woman, it might have read “British Woman Artist,” instead of “girl artist,” but most likely it would actually name her, rendering her fully human. Instead, the “Jordanian girl,” is a thing, not human or adult enough.

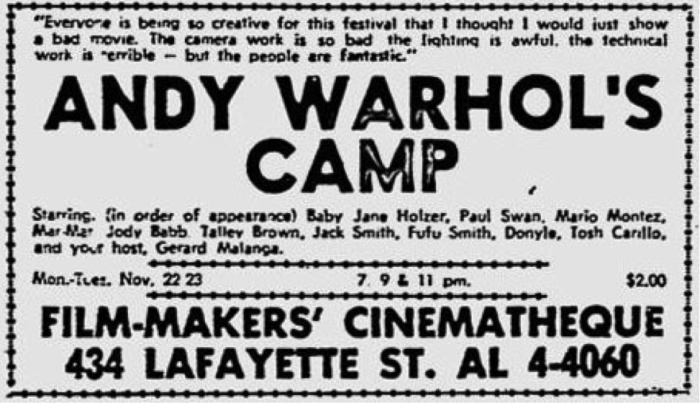

How do we dis-articulate this rationalized way of looking at culture and aesthetics and how can we disrupt tendencies that belong to the domains of “liquidity” and forgetfulness? How do these aesthetics make it easier to sell memories, how can we combat this forgetfulness tied to aspects of capital, this theater of forgetting that plays nightly? The archive is what I may be opaquely referring to as a way of dis-articulating, which then becomes the bad faith in which we weave in and out of memory, the fragments dusted, like some friends and a camera, as is the case in Camp by Andy Warhol.

Camp played with what some call anti-aesthetics, with instances of asymmetry, like zooming in and out at undetermined and arbitrary intervals. Jack Smith, one of the performers, asked something like, “Is this OK Andy?” referring to the actions of his own seemingly undirected performance. It is a scene in the film in which one sees a break with the intentionality of film auteurism, the break with reason. One could have simply edited out that scene to create a coherent edit of the performance. Instead it was left in, B-roll is what they call it. This instance is a type of process and a way of filming and observing that brings attention to the circumstance, the present, if you will. In short, they were playing with the bad, the bad behavior that Marco Ramirez Erre, an artist from Tijuana, told us to keep up.

Although Camp is set in the privileged surrounding of a studio, it does not negate its radical formality. Today we see artists using this indeterminate form that Camp formally whispered – this way of archiving to create political agency around these dis-articulations – a process seen in the work of Harry Dodge and Stanya Kahn, that responds to “eco-social circumstances,” and as Miranda Mellis has observed, it maintains an “ethoi that the personal is political and the aesthetic is ideological… the aesthetic — including, crucially, the anaesthetic, and the anti-aesthetic is leveraged politically.”(14)

The film In Vanda’s Room by Pedro Costa revolves around two women, Vanda Duarte and Zita Duarte – Vanda’s sister in the film and in “real life” (Pobre Zita, who passed passed away after the film). They are addicts living in an impoverished ghetto in Lisbon called Fontainhas. Intercut between various scenes of them smoking and talking in their bedroom, we see footage of Fontainhas being destroyed by a bulldozer. In one scene, while Vanda sits in her room, she coughs up phlegm and covers it up with her blanket, only to continue smoking heroin or crack; sometimes I can’t tell what it is. At first look it would seem that the film is written by the director. At a Q&A at UCLA, Costa said that the cast, Vanda and friends, wrote most of it. This would mean that Costa managed to work in dialogue with them, given that he has made four films with the same cast. Ossos was the film Costa made before In Vanda’s Room and it was made with a conventional film crew and a 35mm camera. After a suggestion by Vanda as to how she would like to be filmed, Costa came with just a video camera, a sound person, and a mirror for light. This was a dis-articulation of conventional process by Vanda, because by changing the format she changed the terms of how the circumstance would be rendered. Zita and Vanda characters as “real people” set the terms for their representation by disrupting centralization, a gesture the anarchists formulated as the “rejection of representation”(15) that since political representation signified the delegation of power from one group to another. In setting the terms of how they were to be rendered, Vanda and Zita intimated that contemporary historiography and its way of documenting actually can’t see them.

Notes:

(1) Dipesh Chakraberty, “Subaltern Studies and Post Colonial Historiography,” Nepantla: Views from the South, 1:1, (2000), 10.

(2)“The Language of Things,” Hito Steyerl, http://eipcp.net/transversal/0606/steyerl/en.

(3)“The Language of Things.”

(4)Gayotri Chakravorty Spivak, An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012).

(5) “On Reading and Rumor, The Problem with Kenneth Goldsmith,” Brian Droitcurt, http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/news/reading-and-rumor-the-problem-with-kenneth-goldsmith.

(6) Gayotri Chakravorty Spivak, “Subaltern Studies: Deconstructing Historiography,” in Selected Subaltern Studies (India: Oxford University Press, 1988) page 6.

(7) “Ferguson Documents: Officer Darren Wilson’s Report,” Krishnadev Calamur, http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2014/11/25/366519644/ferguson-docs-officer-darren-wilsons-testimony.

(8) Adam Waytz, Ken Marrie Hoffman, and Sophie Trawalter “A Superhumanization of Bias in Whites’ Perception of Blacks,” Journal of Social Psychological and Personality Science, Vol. 6 no. 3 (2015): 352, doi:10.1177/1948550614553642.

(9) “Police killed more than 100 People in March,” Carimah Townes. http://thinkprogress.org/justice/2015/04/01/3641143/use-of-force-incidents-march/.

(10) Spivak, An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization.

(11) Franco Bifo Berardi, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance (Los Angeles, Semiotexte, 2012), 70.

(12) Spivak, An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization.

(13) Link to British Movietone Archive film titled “Jordanian Girl Artist,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y9qHOWaL4AY.

(14) Miranda Mellis, “Dissociated/Dislocated: Thoughts on the short videos of Stanya Kahn and Harriet Dodge” in California Video: Artists and Histories, ed. Glen Phillips et al. (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2008), page 83.

(15) Todd May, The Political Philosophy of Poststucturalist Anarchism, (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania University Press, 1994), page 47.

Comments

There are no coments available.