30.06.2018

by Victor Gorgulho, São Paulo, Brazil

May 26, 2018 – July 28, 2018

To define Adriano Costa’s (São Paulo, 1975) artistic practice as “free” is as much an understatement as a trap. We Chose Life . What Now, Georg? Tshirts ?, currently on display at Mendes Wood DM in São Paulo, attests to this fact, crowning a decade of production whose essence lies in an intimate conversation between the artist and his objects—found, borrowed, appropriated from the most diverse sources and origins. Taking on the main hall and the back room of the gallery, Costa exhibits close to thirty new pieces in which he combines and juxtaposes objects in ingenious compositions, including carpets, shower curtains, bicycle wheels, and an array of personal and household accessories.

The artist opts for an installation arrangement of his works, lending a studio atmosphere to the sterility of the white cube. Todos são ele (2018), hung on the wall of the main hall, reads like an introduction (or an epilogue?) to the show: Adriano’s objects are all there, entwined, sagaciously entangled in a schizophrenic visual fabric of personal and political narratives. With sarcasm and wittiness, the artist sculpts the contradictions and complexity of the contemporary political plot in Brazil and beyond. In the Brazil of 2018, the masculine subject of identity not revealed in the title of this work, suggests a regime of alterity surrounded by fear and insecurity. “Ele“, “He”, the other, the one we do not know for what reason he is who he is, but for whom we feed incomprehensible fear.

On a sunny Sunday afternoon following the show’s opening, thousands of protesters have gathered on Avenida Paulista, the city’s main road—just blocks away from the gallery—to demand a military intervention to reclaim the executive branch. Since Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment in 2016, Brazil has seen mounting political upheaval that even the edgiest of historians would have a hard time describing. Far from the old dichotomies between left and right, the ongoing political conflict in the country encompasses an extensive and diverse range of issues, with conservative forces weaving a horizon of hopelessness and ambiguity over the near future. Between prayer circles and impassioned renditions of the national anthem, the protesters on Paulista Avenue that Sunday gathered at the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP in Portuguese) to promote the political campaign of Jair Bolsonaro.

The senator—who is currently at the top of some of the polls for this year’s presidential elections—is a synthesis of reactionary political forces, known as much for his political positions of fascist colors as his insensitive public statements regarding topics such as racism, homophobia, and the indigenous situation in Brazil.

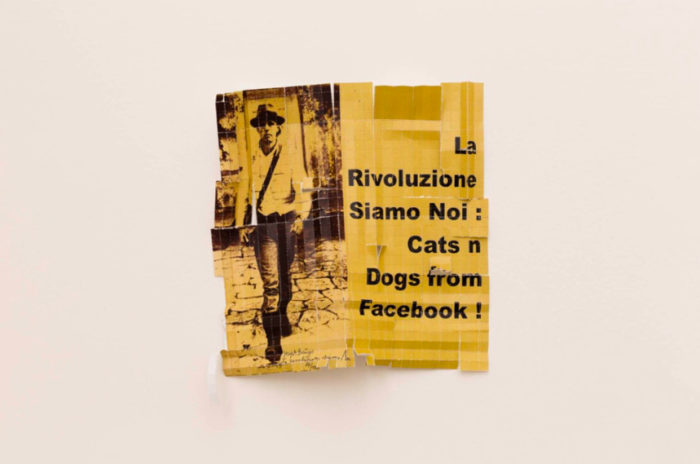

In the exhibition text, Costa writes: “I see this moment, where it seems that we are going back 50 years, full of rules, people wanting a ‘cure for gays’ or a dictatorship, extremists openly screaming in the street at minorities… people like me: an artist and a fag… the title of the exhibition draws us all to a big AND NOW WE HAVE TO DO SOMETHING.” Costa attributes the title of the exhibition to the famous T-shirt worn by English pop icon George Michael in the 80s, with the phrase “CHOOSE LIFE” printed on it. Marcelo C. (2018), gives form to the dystopia suggested by the artist: it is an (inactive) LSD tab in which the figure of Joseph Beuys appears next to the inscription “The revolution siamo noi: cats n dogs from Facebook!” In a historical moment in which political debate is limited to social networks, the artist puts his finger on the wound by pointing precisely to the idiosyncrasies of contemporary habits. Today in Brazil, in the context of Michel Temer’s controversial presidency, there is extensive conversation and organizing in the virtual sphere, but we still haven’t figured out how to develop and realize efforts to move off Facebook and into the streets.

Costa’s new body of work takes to the extreme a sculptural practice that encompasses error and chance, resulting in a visual schizophrenia that seems to update the old problem of the idea of a “Brazilian image.” [1] In 2017, dozens of questionable celebrations were held around the 50th birthday of Tropicalismo, the cultural movement inaugurated by Tropicália, the seminal work by Hélio Oiticica, a Brazilian artist who now occupies an unavoidable place in the most diverse narratives of 20th century Western art history. In Tropicália, Oiticica reconstructed an environment composed of plywood, cheap fabrics, sand, and tropical plants to evoke the precariousness of the vernacular architecture of Rio de Janeiro favelas. In 1967, the work was presented for the first time in the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro. Oiticica sought, therefore, the audacious objectification of the synthesis of a “Brazilian imaginary,” highlighting the crisis of national identity that has affected the country since its colonial days, perpetuated in contemporary times. In the main hall, Costa’s sculptural installation composes an environment that evokes a contemporary version of Oiticica’s piece. His work provokes a diffuse set of questions and urgencies of the now, weaving a visual repertoire that not only gives account of our eternal “vira lata complex,” [2] but assumes, in all its strength and potential, our material precariousness just as Oiticica once did in proclaiming that “from adversity we live.”

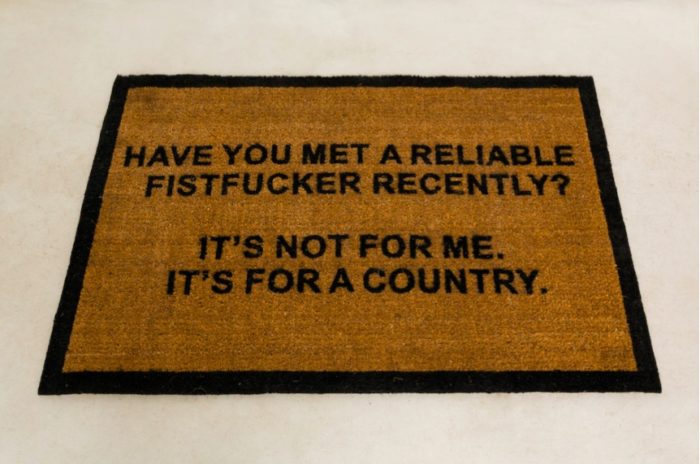

The phantom of the inheritance of the constructivist vanguards of the 1960s, however, does not seem to haunt Adriano Costa’s work as it does some of his contemporaries. If there is a strong tendency in Brazilian art to relate contemporary productions to the artistic legacy of Oiticica, Lygia Clark, and other central figures of this period, in the work of this São Paulo artist, the ghost does not appear so tangibly. Yes, it is possible to draw parallels between the question of objectuality in Costa’s practice and the historical questions put on the table by Neoconcretism; however, the artist rejects the naivety that usually surrounds this type of revision of a canon of the most traditional narratives of Brazilian art history. Fractured, folded, and stacked, his objects challenge obvious classifications and initial readings. They seem to carry with them an awareness of their existence and of the environment in which they were produced, understanding their limitations while seeking to stress political art and discourse. Rejecting the old primer of an idea of “political art” that runs through a considerable slice of contemporary Brazilian production, Costa pokes fun at his practice and at the political context at the same time. “Have you met a reliable fist fucker recently? It’s not for me. It’s for a country,” a small rug screams from the floor of the exhibition space.

In the back room of the show, the artist seems to show this awareness of the limitations and idiosyncrasies of the contemporary art sphere in which this work is born and circulates. Arranged side by side on the wall, the objects seem to be domesticated on canvases, doing the reverse way of Lygia Clark’s infamous neoconcrete bichos, starting from the space to the confinement (comfort?) of bidimensionality. The artist also seems to be well aware of the abyss that separates his political claims, constrained in a lavish gallery space in the Jardins neighborhood in São Paulo, from the demonstrations just a few blocks away on Paulista Avenue. So close, so far.

Costa’s visual grammar seeks to embrace the schizophrenia of the plurality of contemporary patterns. Armed with the typical irony of the Internet age, the artist easily migrates from national ills to foreign news, from the question of refugees to the faint-hearted imagery of consumption in late capitalism. The idea of synthesis posed here goes beyond national boundaries and offers a reflection on the status of the image in contemporary times, in the era of fake news and the pixelated images of Instagram “stories.” At the end of the course proposed by Oiticica’s Tropicália, a small TV timidly rests intermittently on the gray hiss produced by television sets when it is impossible to transmit an image. The small television closes the path of the penetrable, suggesting a devouring of the images placed therein. Between synthesis and the impossibility of synthesis in the nebulosity of the intense now, the visual syntax of Costa seems to reverse the logic of Oiticica’s TV. Irresolute, pixelated, hesitant, the images created by the artist are the ones that devour us, and not the other way around, after all.

—

[1] In: Tropicália: o problema da imagem superado pelo problema de uma síntese. Hélio Oiticica, Londres, 1969.

[2] An expression created by Brazilian writer Nelson Rodrigues to designate the social trauma that exists in the Brazilian collective imaginary following the loss of the World Cup Championship in 1950, held in Rio de Janeiro.

Comments

There are no coments available.