02.10.2021

”Although in the face of the rise of photography, the term real has become increasingly alien to the pictorial, in its condition as an image, painting can touch reality through formulas that burn in the midst of historical contexts, in which critical knowledge about images is produced.”

When reflecting on visual arts and historical returns, it becomes necessary to establish a difference between “the return to an archaic form of art that encourages conservative tendencies in the present, and the return to a lost model of art made to displace traditional ways of working”.[1] A clear difference on which it is legitimate to wonder if it’s possible to determine—today—some lost model of creation, while we live in a continuous interweaving of historicities, languages, and resources only possible by an era of superimpositions such as ours. Despite the distance from the pure and inalienable disciplines of the past, current artistic manifestations are unavoidably framed in a genealogy of disputes, characterized by the presence of themes, strategies, and forms, among which painting, its expiration, and validity, has occupied a focal and substantial space of debate. A long-standing issue that has pushed the limits of pictorial representation to experiment and mutate, to the point of making the painters’ exercise a space of anachronisms and possibilities for imagination and realization.

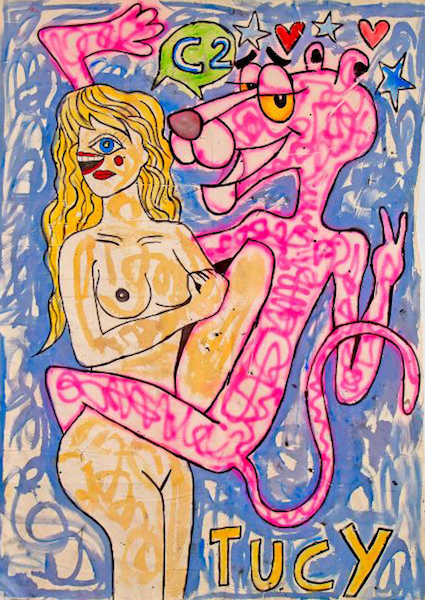

In an intelligent review of this process, Luis Salazar expresses in Art in America an exercise of history, montage, and dialectics between urban objects, elements of popular culture, and post-war avant-garde artistic languages. While his painting challenges the linear discourses recognized by the history of Western art, Salazar creates a space of formulas and diagrams with which he establishes expansive visual and linguistic relationships (neither immediate nor easy to understand) that wander through both figurative and abstract poles of modern art. Regarding the latter, the works presented here represent a paradox of abstraction; while 20th-century geometry “doesn’t recall—nor should recall—anything, does not suggest anything, nor resembles anything”,[3] Salazar’s forms operate as sharp imitative appropriations, without leaving aside the crisis and degeneration that all imitation contains in itself.

In a country like Venezuela, brief but intense decades of modernization have established to this day an abstract-geometric imprint, which opposed to the figurative heritage, generated at the time one of the most heated intellectual debates in the history of Venezuelan art: figuration versus abstraction. Absolute antonyms that seem to dissipate and coexist in an overlapping present through their ways of assuming the real, from their isolation or their penetration. Thus, Salazar’s insertion of oppositions between representation and abstraction opens a parenthesis in our discourse that allows us to return to an old dispute: the place of figurative painting.

In his recent book, La (in)actualidad de la pintura y vericuetos de la imagen [The (In)actuality of Painting and The Twists and Turns of Images], Luis Pérez-Oramas vindicates the spatial nature, the heights, the thicknesses, the densities and materials of the pictorial object, while asking “how did an ideology of images impose itself so resoundingly on the concrete reality that a painting is, before being a painting, a thing and as a painting, also as an object? (idem). Recovering its objectual condition, Vivenes’ painting embraces and adopts formats that make it an artifact, sculpture, assemblage, material and corporeal exploratory of symbols (in this case, patriotic), which desacralize and profane the iconography of Venezuelan power, and with it, what they represent for the collective memory.

For its part, from this mnemonic place, figuration establishes symbolic links with nature “from which it has been extracted and to which it refers back”.[5] “Twists and turns” in which Rafael Arteaga’s Crónicas Fantásticas are inserted, making the trap warned by Pérez-Oramas a lead on the contemporary image. Found in an archive of intangible surfaces and hybridized with photographic memories, the images selected by Arteaga (among a large repertoire of two-dimensional mirages provided by the internet and the findings) take on the body of painting through hilarious visual constructions, light, fast and digestible; works that touch the real from the implausibility that opposes realism to fantasy: are these scenes true, to what memories do they refer us? What happens when, contrary to the trap, an image becomes pictorial density?

—

Luis Salazar, Art in America

Carmen Araujo Arte, Sala TAC, Caracas, Venezuela

July 8 to October 3, 2021

José Vivenes, Doblepensar

Spazio Zero Galería, Caracas, Venezuela

June 12 to September 27, 2021

Rafael Arteaga, Crónicas fantásticas

Beatriz Gil Galería, Caracas, Venezuela

July to September 2021

Hal Foster, El retorno de lo real. La vanguardia a finales de siglo (Madrid: Akal, 2001

George Didi-Huberman, “El archivo arde”, en: Georges Didi-Huberman y Knut Ebeling (eds.) Das Archiv brennt (Berlin: Kadmos, 2007)

Xavier Rubert de Ventós, El arte ensimismado (Barcelona: Anagrama, 2006)

Luis Pérez-Oramas, La (in)actualidad de la pintura y vericuetos de la imagen (Valencia: Pre-textos, 2021)

Idem.,Xavier Rubert de Ventós.

Comments

There are no coments available.