09.05.2021

I love you, cultural work, but you are bringing me down.

“I count things as I see them,

But what if I happen to be nearsighted. “

In an article published in 1996, a correspondent for The New York Times described Oaxaca as an “artistic epicenter”. My father, a valley Oaxacan, best sums this up in a joke that says that when you lift a stone in Oaxaca, an artist runs out (sometimes up to two and lately also cultural managers).

I clarify that I do not seek to make a pretentious recount of the multiple disciplines that I abandoned during my life, rather I seek to find a commonplace among all of them: I never paid a damn coin to learn or attend all the workshops that I took growing up in Oaxaca. Something I never questioned myself until it was my turn to be on the other side, the counter-narrative of this cultural epicenter, the side that does not take the workshops or attend the exhibitions, but rather imparts, manages, and executes them.

It must be understood that in Mexico there is a long race of geographical, economic, educational, and symbolic obstacles in order to approach museums and cultural offers.[1] A race that, thanks to the proximity and gratuitousness of the institutions in the state of Oaxaca, has fewer obstacles than in others parts of the country. So, as Oaxacan children, it is very easy for us to fall in love with art, music, theater, books, because it’s every day sucked—where if your parents work during the afternoon, the house of culture was the option to hang out. However, as cultural workers, this love is now a toxic relationship.

I love you, cultural work, but you are bringing me down.

Although there are already some formulas that artists have developed to position themselves within the dark matter[2] of culture in Oaxaca—such as the IAGO formula, being part of the istmo-meritocracy or the vectorized black and white photo-mural with the image of poor people pasted outside the fashionable restaurant (stop this, pls)—the reality for many of us, in my case as a curator, is that the economically profitable labor field in the state is almost non-existent (symbolically profitable, there is a lot).

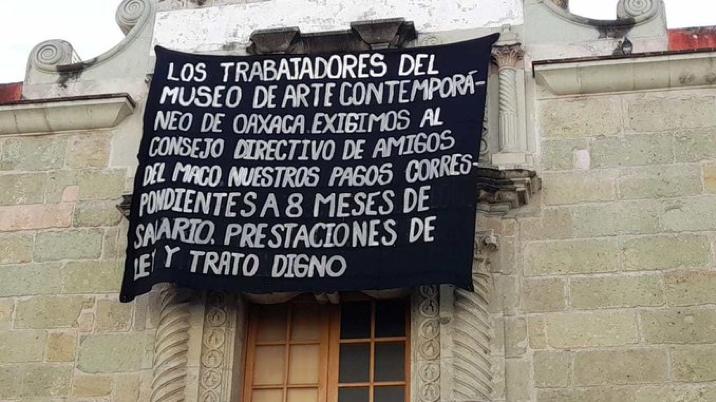

If a project does not charge, it must receive inputs, sponsorships, or money from somewhere, right? Where is there money for art workers to continue working and thus obtain what is necessary to live with dignity? Because like any job, cultural work must be paid for.

The first answer that comes to mind, understanding my paternalistic cultural education in relation to the number of institutions in the city: the Culture Secretariat, SECULTA, receives 180 million 748 thousand pesos a year.[3] Only 9% of this budget results in cultural promotion actions, the other 80% goes to employee salaries and the remaining 11% corresponds to operating expenses.

But for years we have not seen any initiative on the part of SECULTA that is linked to current production and promotes it. I am talking about current production because this administration dedicates funds to an idea of culture that belongs more to those who visit us than to those of us who inhabit this state (even for several years the SECULTA was merged with the Ministry of Tourism, SECTUR).

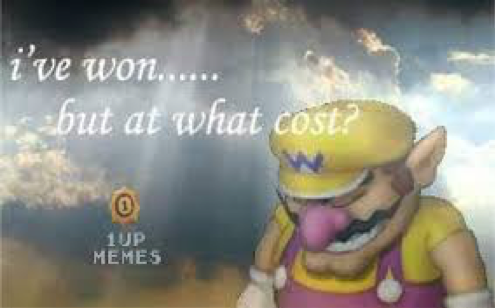

Oaxaca, for better or for worse, lives off tourism and of an idea frozen by the exoticism of the Oaxaca experience that dresses in linen to walk around the city and uses suede hats in terracotta tones. This experience asks us not to modify traditions, that we show up to dance on the hill every Monday for national and foreign visitors as if time did not pass here; as if the Indigenous peoples did not migrate or cultivate in new practices, economies, or interests. They look for us because we paint with land, minerals; because here there are iguanas, Tehuanas and everything is very cheap. Maybe that’s keeping us alive economically, but at what cost?

The contemporary artistic proposals produced in Oaxaca are not being collected and even less financed. The only two galleries that really make the effort to position their artists’ work in the 40+ age sector, very viciously unify the aesthetic proposal of their artists’ plastic formality with the vision of the exotic market that we represent abroad.

Talking with some colleagues, it is mentioned that the management of mixed economic models and private sponsorships will save the culture and arts workers of this city. On this, I have more doubts and conflicts than answers. Meanwhile, I appeal for the redistribution of money dedicated to promoting culture for tourism purposes towards the promotion of conditions that allow institutions and independent spaces to continue offering gratuity and fairly paying those of us who support that possibility.

From my trench, about to be graduated, with two jobs in the arts, a kombucha venture, and giving yoga classes, I wonder if living here, in the city of Oaxaca, I will be able to live off my curatorial work at some point. I also wonder if when the next Latin American Census of Art Workers arrives, I will be able to answer that I do have a contract and I am receiving social security. Or if maybe the market will defeat me and my desire to continue dedicating myself to contemporary art. If I get tired of being in constant scrubs all week in order to continue being an art worker, and dedicate myself to Zapotec wellness in this city on the verge of losing itself in tourism. Meanwhile, here we are, taking the streets with community-funded proposals because we don’t fit into the institutions of this city.

Resist, resist and resist. And then what do we have left? The sum of all the forces.

Ana Rosas Mantecón, Barreras entre los museos y sus públicos en la Ciudad de México Culturales, vol. III, núm. 5, enero-junio, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Mexicali, México, 2007, p. 79-104.

This term is used by Gregory Scholette to describe “a dimly lit creative sphere largely excluded from the economic and discursive structures of the institutionalized art world.”

Within this little research, I found that the “Transparency” tab of the governments’ web page is empty, lol. https://www.oaxaca.gob.mx/seculta/transparencia/

Comments

There are no coments available.