22.07.2017

by Marilia Loureiro, São Paulo, Brazil

June 27, 2017 – July 30, 2017

Osso: brutal and common

Osso – Exposição-apelo ao amplo direito de defesa de Rafael Braga (Bone: An Exhibition/Call-to- Action for Rafael Braga’s Broad Right to Defense) has been mounted at São Paulo’s Instituto Tomie Ohtake in collaboration with the Instituto de Defesa do Direito de Defesa (The Defense of the Right of Defense Institute; acronym in Portuguese: IDDD), a civil-society organization on behalf of the public interest that advocates guaranteeing all accused persons’ right to legal defense and to serve sentences with dignity. This joint-effort between a cultural institution and a legal-and political-action- related NGO came about because of the show’s subject: Rafael Braga and his various arbitrary imprisonments.

About Rafael Braga

In June 2013, Brazil was overwhelmed by a wave of protests in which millions of individuals took to the streets in more than 100 of the nation’s cities. Among those the police detained for questioning, Rafael Braga was taken into custody for carrying two plastic bottles of cleaning product that supposedly could be used as Molotov cocktails. Unlike others arrested in that setting—mostly middle-class whites—Braga was young, black and poor, and worked collecting cans for recycling. Although investigations concluded the products found in Braga’s possession could not be used to fabricate a homemade explosive device, the young Rio de Janeiro resident was sentenced to five years’ incarceration, based solely on two police officers’ testimony. Braga was the only Brazilian citizen to receive a jail sentence in the context of the 2013 protests.

After serving some of his sentence behind bars, he was finally paroled and began to work as an administrative assistant in a law firm. However, in January 2016, Braga was jailed a second time. According to police accounts, the young man had been caught in possession of .6 grams of marijuana, 9.3 grams of cocaine and a firework. Braga, who denies all charges, alleges he was the victim of police violence and extortion. Based solely on statements by police who testified at his trial, he was sentenced to eleven years and three months’ prison time for drug-trafficking and unlawful trafficking associations. Braga is just one case among highly elevated statistics related to police violence against black, poor and marginalized populations, mass incarceration, selective sentencing and the normalization of a permanent state of emergency.

The exhibition

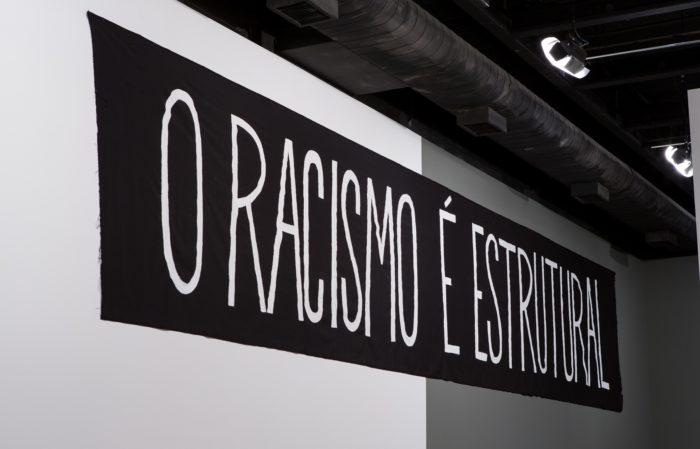

Based on an invitation from curator Paulo Miyada, twenty-nine artists are exhibiting works that deal with the Rafael Braga case; almost a third have never been previously shown. According to the curatorial text, the title, Osso—i.e., “bone”—references a works-selection based on minimal elements that synthetically reflect the fragility and cruelty of questions related to the right to a competent defense. In addition to the artworks on display, there is an adjacent space where a number of documents the IDDD has compiled on the Rafael Braga case are presented. A public calendar of debates, documentary films and theatrical works is also part of the exhibition.

Osso overflows with what most shows today seek to avoid: contradictions. If indeed it is common to find exhibitions illustrating contradiction, domesticated within a notion of plurality, Osso internalizes a series of incongruences and tensions within its structure that expand the potency of viewers’ contemplations. We’ll briefly deal with one here: the disconnect between the reality the show’s provocative theme takes up and its translation into the realm of the sensible.

The minimal elements present in the pieces on display, such as threads, mechanical pencils, books, stones, projectiles and coins, inevitably call up political approaches by means of sophisticated abstraction- and formalization-maneuvers proper to contemporary art. This is the case in Cruzeiro do Sul (1969-70), by Cildo Meireles, a nine-millimeter pine and oak-wood cube, presented directly on the floor of an otherwise empty gallery. These woods, that indigenous peoples used to rub together to start fires, alongside the title, that makes reference to a constellation that can only be seen from the Southern Hemisphere, count on the audience’s capacity for analogy to activate the artwork and give rise to political, geographic and social notions. Another work that plays with minimal elements is Sem título (Fita 5), from 2017 and by Iran do Espirito Santo. As is his wont, the artist used a single medium to construct the piece, made up of strips of tape affixed to the wall, often overlapping to create a sort of synthetic, pictorial screen. Elsewhere, Um milhão de reais (2010) presents a 50-centavo coin directly on the floor, protected by a large isolation zone. The work, by Clara Ianni, contemplates abstract economic concepts, also present in art, that wield significant social impacts.

Approaches between episodes from the Rafael Braga case and the works on display seem to make clear there is a major disconnect between life and ways of representing it. The quid pro quo in that situation is believing in an equivalence between certain terms that are neither equivalent nor are represented in such distant contexts. What might be called harsh within the show is something very distant from what harshness is taken to mean in the outside world, just as a notion of precariousness in contemporary artworks lies very far from precariousness in life. Osso’s poetic attempts to approximate certain social subjects’ vulnerability in Brazil via the fragility of simple objects that have been stripped of matter, is brutal and at the same time highly common, just as in Braga’s case. The fact is, no representation of reality can entirely coincide with that reality, but over the years, the visual arts in Brazil have reproduced a type of representation that all but completely lacks both the signs and the subjects of exclusion that frame our society’s dynamics.

Osso therefore cultivates a perverse game that oscillates between urgent presence and Rafael Braga’s utter disappearance from the exhibition that bears his name. It might be a case of contemplating art’s crisis of representation, that sets aside the correspondence between reality and the sensible forms that seek to represent it. Maybe it’s us remembering once again that the disparity between representation and that which we know to be its harsh context is an older national question—the displacements of an inevitable maladjustment to which the colonialist machine condemns us. So there’s little point in accusing Osso of being contradictory, perverse or untrue. Maybe the more interesting thing would be going along with the fact that in these movements, falsehood is precisely the part that’s true.

Marilia Loureiro (São Paulo, 1988), graduated in International Relations in São Paulo, with part of her studies at Institut d’Études Politiques de Paris (Sciences-Po), also holds a Master degree at Programa de Estudios Independientes (PEI) at Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Barcelona (MACBA). She has worked on the 29ª Bienal de São Paulo, on the curatorial cores at Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (MAM-SP) and Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP). Loureiro also took part as resident and researcher on independent spaces as Ateliê397, Casa Tomada and Capacete. She was the guest curator at lugar a dudas, in Cali, Colombia, between August 2015 and March 2016 and is the current curator at Casa do Povo in São Paulo.

Comments

There are no coments available.