Reading time: 10 minutes

12.11.2017

Lodos, Ciudad de México

October 7, 2017 – November 18, 2017

Diego, papito, papá Pinillos,

Before the past takes everything away, I would like to share with you some images that have stuck in my head. Actually, they all talk about the past, so don’t feel the need to trust them. Inevitably they will disappear. They are only representations. Ideas about you. Or rather, reproductions of you.

** ** ** ** ** ** **

I met your mom; I once went to her house in Coapa. Do you remember? I remember your room. It seemed to me that everything had an unexpected order. There was an organization that made me trust more in your way of perceiving the world. Of your brother I only remember when you told me that he had a ramen business, which you had helped him set up and manage.

I also remember that you worked managing the social networks of a taqueria. Is that what you call a community manager? It was 2010.

From your old man, I know a picture you painted trying to reproduce a family photo. When I imagine it, it seems to me that where your father’s face is, I can only see your’s. You also told me that he liked to dress elegantly, and so you painted him that way. He was probably a good guy like you.

Cheers, to all those who left. Cheers and anarchy.

I remember that in the National School of Painting, Sculpture, and Printmaking “La Esmeralda” everyone called you Cyborg. And that during class you would make music with your iPad; which many thought was not music. I cannot remember the exact day we met. You were two generations under mine (by the way, did you ever graduate?). Maybe it was when we invited you to the noise show in Fermin and Joel’s little stand. Or in any of the student assemblies in the yard? Most likely, it would have been while smoking a joint in the sculpture studios. Either way, we connected, we talked and talked, projecting our interests and desires. We liked relational art and pieces with everyday objects. We loved knickknacks. But above all we liked to talk, to talk and to listen.

Only a few know why they call you Pini. I still do not remember. Or I did not see the full movie. You never see the full movie and yet one remembers. Recreates.

In 2011 a professor invited you to exhibit in a gallery of the UAM, maybe it was your first show and you were afraid. Maybe that’s why you invited us to do the project together. You, Juanpi and I. El “Laboratorio de Manchas y Gritos” (The “Smear and Scream Lab”). We used my brother’s van to produce all our little mess. Buying furniture, props and toys for the installation, in the Salado market. How we love the knickknacks, fuck! The piece was a kind of a habitable installation, which served as the basis for giving a workshop to the children of the gallery workers. We were interested in the social. Not that we longer aren’t, but maybe we’re not?

The following year we marched together believing that something really would happen. That the PRI would not return to the government. Are we still so naive? Or can we call it dreamers? Or will it be that we do not even care now?

More years went by and you went to the north of the country, you were Teresa’s assistant, you put together the Altavista Archives, you lived to the limit. They deported you from the USA for some photos where they see you smoking. And because you were bald and without eyebrows. And because you’ve always been very special. Or as they called you, you’ve always been an Alien. We would talk on skype and argue about identity. Of how identity was understood in the north of the country.

Rumors say you were selling acid. Others that you still are. Small pieces of paper with fragments of unrecognizable images. Almost like memories. Or like dreams.

We spent one of your birthdays at your friend Lauro’s flat in Condesa. It was the first time I heard Trap. Before it was reggaetón. The original Atlanta Trap. We watched videos of the crew dancing and we imitated them for hours, just right before the blow showed up and I had a bad trip.

Then you went to London with Angela. And you continued working in the Altavista Archives. And we kept skyping and talking about politics. And we thought we were artists. To live in an alternate reality. And you invited me back to do something together. To share my vision of the world. My world. And I talked about Mexican history. And you burned copal in a gallery in Paris a week before.

I have never understood the time in which you live. Or why you’re not interested in clocks. Protopias.

You returned to the monstrous city and I invited you to Cráter, to do a show in the small battered and underground gallery in San Rafael. And you decided to live in the house to plan the exhibition; and a friend of yours threw up on the stairs. But you also organized a study group on violence. And Mexico is still violent. Today I read that 2017 is the most violent year in the contemporary history of the city. Let’s not forget that the year is not over yet, and that you never did the show.

I also remember you slowed down a Fey song. “Azucar Amargo”, and it makes me think how hyperactive we can be as humans. Even if we slow down the songs.

It’s like a year ago in Oaxaca. We tried to do a play and they censored us. It was a play about us, a representation of reality. A tautological game. Were we so politically incorrect that we selfcensored? Maybe all this time, we’ve just been naive provocateurs. Clowns without a nose.

Or when you showed me your exhibition in Lodos. I remember there were white, empty walls on a blue floor. Without art. Just friendship and words.

– Juan Caloca

The first time I saw Diego was at night on the roof of a house in the Escandón neighborhood. I was talking with artist Temra Pavlović when Diego approached us to greet her. Diego and Temra knew each other from before and without an introduction he began to talk about an exhibition that he had just visited.

“Look, it’s the hartos, the hartistas!” He explained to Temra enthusiastically as he showed us a small publication he had acquired from that exhibition. Diego explained in detail the story of the hartos, what he understood of them and what he felt for them. I did not exist in the conversation; all attention was directed from Diego to Temra, and from Temra to Diego. My attention was diverted and after what felt like an hour, Diego left.

“And who was that?” I asked Temra.

“Do you not know Pini?” She replied with a surprised tone.

“I do not. Who is Pini?

“Pini is an artist … well a poet, well … an artist who writes.”

After that night I started to encounter Diego in different exhibitions and parties. And what does he

do? I asked.

“Who? Pini?

… he is an artist … he is a poet … he makes movies … he writes … he makes music … he cooks “

“He just returned from a residency in Ciudad Juárez”

“… he sells acids…”

“He was going to play at a festival in Austin and they did not let him cross the border.”

“He was deported, he had shaved all the hair from his body, head and face.”

It was on a trip to London where I finally got to know Diego’s work. I had been invited to participate in an exhibition and on that trip I met several friends, one of them Temra, who told me that Diego was in the city doing a residency in MayDay Rooms. Diego had invited her to a screening that night.

“Come with me, and we can visit his studio on the way,” Temra proposed.

Diego met us at the entrance to a building at 88 Fleet Street, just across from Goldman Sachs corporate offices. He’d grown a beard since we’d last seen him. We went up to his studio from which you could look through the windows of Goldman Sachs. His studio was full of documents and posters. He told us a little about his residency and that he was there in particular to work on his project the Altavista Archive, which was a praxis lab that Diego worked on in the Altavista high school of Ciudad Juárez. This high school’s patio neighbored with the border of the United States.

He showed us a stone. Or a crystal, I do not remember very well. He had brought it from Mexico to London in his suitcase. Diego showed it to us with such care. When we finished talking about the stone, or the crystal, I do not remember very well, he repacked it with the same care. “It was a hassle bringing it through customs”, Diego told us. I laughed, and thought such a hassle for a fucking stone? How much affection for a thing?

I returned to Mexico, and Diego was returned to Mexico. I heard that he had been deported again, now from England. “He overstayed his welcome,” they would tell me. We would see each other; we would greet each other again. More than once he approached me and from the pockets of his clothes he would pull out something, a something, a thing, a knickknack. “Look, it’s my new piece”, “Look, my new drawing”, “Look, my new sculpture “. A bottle cap, a note on a crumpled paper, a stone.

How much affection for those things? I kept asking myself.

Diego would tell me the story of such objects. He found them, they came to him, he manipulated them with anecdotes. He gave them order, he gave them function, he gave them a process. But, it’s a stone. But, it’s a paper. But, it’s a nothing. I would say.

We got to be classmates in a workshop. A New York artist asked the participants to design a clock. During the two weeks of the workshop, Diego did not show up or came in late, ironically. On the last day we would all present our clock, Diego was the last to arrive and would be the last to present. While the others presented the results of the project, I observed Diego. He had a notebook in which he wrote, he would stop and stand in the library where we all were presenting and he would grab a book. He would skim through it, read a few pages, and set it apart. He would go back to his notebook, write something, and stop. He would grab a new book, flip through it, read it, set it apart. He repeated this process until the time of his presentation.

“Please, let’s go outside,” he told us. He grabbed all the books he had set apart and we all went out into the garden. It was already night. “This is my clock,” he said, showing us a smooth gray stone with a hand-clock drawn with marker on it. “This little jar is also my clock,” Diego said while showing us an empty perfume bottle.

“Lie down on the floor, please.” Diego read to us the fragments he had chosen from the books he had just selected. At the end he asked us to breathe and to open our eyes. His clock and his way of marking the time had come to an end.

His clock-hands: objects and words.

– Francisco Cordero-Oceguera

***

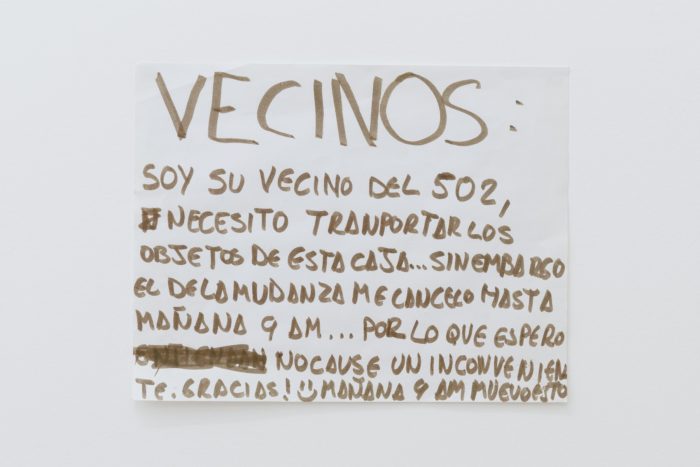

Nunca Godo is Diego Salvador Rios first solo exhibition at Lodos. The exhibition addresses topics related to class, family, friendship, affection, social mobility, bionomies, management of power, administration of life, definition of the private and the public, distribution of the sensitive, dualisms and separatism, among others; from an autobiographical point of view that from the personal speaks on the conditions of the contemporary artistic practices and ways of life today.

Diego Salvador Rios (Mexico City, 1988) is an artist and researcher. His production is based on the poetic production in terms of language and relationships, for this he explores the intersection between art and curatorial practices, mainly through the construction of collective situations and experiences that investigate the politics of representation and the production of knowledge.

***

Comments

There are no coments available.