17.07.2021

This set of works illuminates a common genealogy in these regions called Latin America and the Middle East (oppressive political regimes, cycles of immigration, expropriation) to dive into an excavation, that of a dialogue between artists from these regions, and find links that connect the territories in their narratives.

“When our story is told, the story of our people is going to be told.”

The stereotyped representations from Western thought create certain violence and beliefs about ourselves, a millenary story repeated over and over. How to shake off a belief that’s held with such expensive foundations? The importance of stories in our configurations of the world, of our communities, and identities should not be underestimated. What is named, happens.

I recognize the difficulty of not romanticizing the revolutionary processes as if the colonizing seduction did not exist in us: At whose expense and of how many do we find ourselves alive and being able to write a text or make a film? I dare then to present my cardinal points as reminders to approach this program without flattening its reliefs: 1) Peoples are reborn because they organize themselves. 2) Films do not portray any defeated people. 3) Western discourses are not an inheritance. 4) Poetry is also a gesture of denunciation.

Thus, we suppress the euphemisms of saying “conquest” instead of “robbery,” “disappearance” instead of “genocide,” “conflict zone” to portray a city in flames.

The eternal bosses and owners who ponder wealth over life, are the same ones who held the microphone burying the lower voice and subjectivities. Villages turn pale from dust left behind by destruction and bombs. A cloud hangs in the air; it is the shared history, the history of our ancestors: the roots are united in some deep layer that is difficult to dig with our fingernails.

The foreigner with a camera, the tallest one in sight, historically, speaks in “place of,” the same joke over and over again.

Artists and curator seek to meet in an exercise of (dis)identification: they quote each other, they name each other, they provoke memories of their countries and families, someone was a reference and teacher for another, many recognize themselves in exile and answer, unwittingly, questions they asked years ago. The works form a game of mirrors and begin to speak on their own when the playlist is activated, a space-time where bodies are recognized and words travel like an echo. Someday it will reach another desert.

Is emancipated aesthetics possible?

As borders mark the land and declare boundaries to disconnect territories that are contiguous, this project invites us to scrape the edges so that they get diffused—part of the school map is forgotten and some cities get closer. The discourses are connected: a healing act (as if the metaphors were enough), to elaborate poetic revenge, taking a place that was denied to them, seeking to disarm a power structure. And although these films emerge at different points on the map, they are born in the swirl of an ongoing struggle and create a family of voices, perhaps a chorus.

Donna Haraway (this lady deserves that I steal the concept) throws this possibility, that of “creating kinship”, that of communication and community (video-correspondences) in working with others. It’s like writing a letter from a distance (that of time) that does arrive… and the years overlap. I guess it’s similar to seeing an unknown person on the street who reminds you of an aunt.

Under this claim, one of the artists in this program, Elena Tejeda Herrera (Peru) comments about her performative work Recuerdo [Memory] (1998): “I presented myself in a huge black plastic bag, like the bags where bodies are stored in morgues. A man carried me from a hidden place to a corridor inside the university and placed me on the floor, near one of the rose-tainted windows, and then walked away. After a moment of silence, I began to sing the following lyrics from a well-known Peruvian waltz: Hate me, have mercy, I beg you. Hate me without limits and without mercy. Your hatred I want more than your indifference. Because hate hurts less than oblivion.” The exercise of memory appears from the body in a real scenario, it reassembles violence (the massacre of nine students by the Peruvian army) and embodies it. The audience witnesses a raw temporality in front of them, a demonstration.

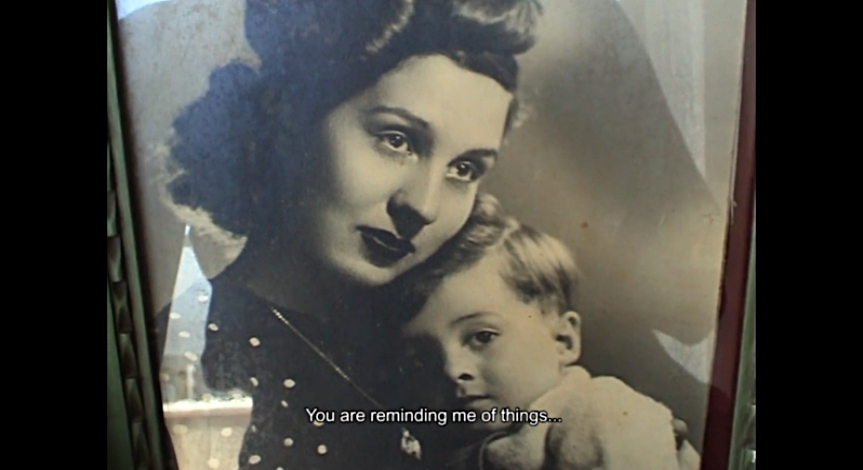

Measures of Distance (1988) by Mona Hatoum (Lebanon) is an archeological tale of exile and the distance caused by war. She turns to the archive to relive the past and reads aloud her mother’s letters as they are overprinted with family photos. “I hope you come to visit soon,” she stresses. The family’s private conversations creep in and childhood comes up, what they didn’t dare to say to each other when they lived in the same home. It gives the sensation of getting closer and closer to their intimacy, recognizing traits of those women in the room talking, nostalgia creeps in and inaugurates a silent room where we are the only ones eavesdropping, placing our ear on the door to hear the whispers “You know… in this country…”.

There is no exclusivity in wounds, everything has to do with everything.

In Vacas [Cows] (2002), Gabriela Golder (Argentina) films her television screen. The pixelated frame shows the news of a group of neighbors who rob a truck of cows overturned on the road, the scene shows, in the background, teamwork, the organization to avoid starvation, further back the economic crisis in 2002. The scene is visceral, the artist disarms the show with shots and zooms, she does not hide the cut, she builds a soundtrack of rupture and tension.

Akram Zaatari (Lebanon) invokes anecdotes with a live camera, dedicates a letter; (an invitation or a farewell?) Red chewing gum (2000) is an erotic short film that treasures what no longer exists, the landscape of his neighborhood when he was 15 years old, and the relationship with his ex-boyfriend.

Now a Coca-Cola truck parades through the city, it’s the only thing that shines on that street, a group of children waving at it from their parents’ shoulders. The balloon is punctured when the montage interrupts with an irreverent game: it invents scenes with the same materials. Through the strategy of irony, this found footage called Cinépolis, la capital del Cine [Cinépolis, the Capital of Cinema] (2003) by Ximena Cuevas (Mexico) turns our daily life into a horror movie. Jayce Salloum’s Introduction To the End of An Argument (1990) responds to it as a continuation, it opens the cinema within the cinema: it disarms and emulates a Hollywood film using recognizable and hackneyed resources of comedy and action cinema. The entire film revolves around the promise of the US-American dream by pointing out racism with dense humor.

Reviewing the stories with which we have grown up and dismantled them hides a power: to narrate and name ourselves. How can we not think of disarticulating such sharp rules embedded in our habitat: idols, language, encyclopedias, festivals to which we apply to be chosen?

Comments

There are no coments available.