14.12.2017

By Andrew Berardini, Los Angeles, California, USA

June 11, 2017 – October 15, 2017

All of our homes and would-be paradises: the Utopias we dream, our parent’s fantasies and realities, the homes we come from, the one we live in now, that place we fantasize about; all of it layered, one room leading to the next, one home leading to another.

Our attempts at making a home are always aspirational, a reach for a better place, ever closer to perfection. Utopia’s always a fiction on the far side of the horizon, somewhere over the rainbow, in the Big Rocky Candy Mountain [1]. But we aim for it because what we have has failed us and we have just enough hope and confidence to make something better, or at least attempt to. Even if often co-opted, capitalized upon, and defanged of all its revolutionary fire in time, each attempt for a better life affects others, inspires and challenges those that come after.

We edge closer, as close as circumstance allows, to paradise. We do our best to make a home.

Here at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (and now in the Museum of Fine Arte of Houston), forty-two or so Latin artists from the US and Latin America–with an emphasis on Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Mexico–with over 100 artworks explore, confound, dream, and remember home. As the opening salvo of the Getty’s region-wide initiative “Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA” –exploring Latin art from across the Americas– this exhibition provides a literal home as a place from were the rest of PST can spread into hundreds of other venues across Southern California.

The exhibition curators, Mari Carmen Ramírez, curator of Latin American art at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston; Chon Noriega, of UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center; and Pilar Tompkins Rivas, director of the Vincent Price Art Museum at East Los Angeles College, pulled the name for their exhibition from Richard Hamilton’s iconic pop collage from 1956, “Just what is it that makes today’s so different, so appealing?” A question easily pulled from that era’s post-war fantasies and consumerist yearnings and preening in the piece itself: a hunky bodybuilder fisting an oversized Tootsie Pop; whilst on the sofa a busty and pastied lady arranges her mostly unclad body just so, with canned ham and vacuum cleaners and a sparky television all beaming out. A sarcastic layering of all our advertised hungers collapsed into a living room. At LACMA, the subtle and not-so-subtle explorations of this topic hints at the conditions and realities of Latin Americans where ever they’ve made home.

Where and what is home? The place where you keep your clothes. The space you sleep. The things you carry. Where you hide out. Where others can find you. Where your loved ones wait for you. What’s left behind. A place of aspiration or the hard reality of whatever the struggle to find comfort and safety might be.

Or even sometimes, home can be where they live, where they hide out, where they find comfort and safety and not you do not.

Los Angeles’ Daniel Joseph Martinez’s recreates the Unabomber’s cabin painted with the Martha Stewart Collection’s preferred colors for this season’s home and then splits it down the middle in homage to Gordon Matta-Clark’s iconic “Splitting” (1974). Titled “The House America Built,” an anti-technological home-grown American terrorist finds his drop-out cabin adorned with the hypercapitalist normativity of America’s favorite corrupt homemaker (the hues like creamy popsicles for comforted children). Matta-Clark’s architectural interventions, building’s sliced and topped, punched holes in what reality and the buildings we live and work really mean and his split house opens up the privacy of the lives lived indoors to literally reveal what lies within. In a single work, Martinez collapses the polarities of our worst fears with our most commercial aspirations and reveals with a referential slice not only the interior polarities of terror and capital that built too much of a country that 323 million call home, most of whom left their homes elsewhere or are descendants of the same to make a new one here.

We leave where we were born for a reason. Moving on we hope to move on.

And Abraham Cruzvillegas, an artist from Mexico, scraps together a home as he did where he grew up –in a place of poverty you make it yourself with what’s a hand– a process he call autoconstruccion that here becomes a rich site of metaphor. In Miguel Angel Ríos video The Ghost of Modernity (Lixiviados), 2012, shacks scrapped together from rusted corrugated metal and whatever else can be salvaged fall from a sunny sky, one after another, onto a rocky plain. The title hints at the cube as a unit of modernity, and the “ghost” perhaps it’s broken down incarnation here. Watching shack after battered shack land on the rocks feels almost funny, a comedy of the absurd. Dorothy’s Kansas home tornadoed all the way to this very earthy landscape, but these building are so downbeat, broke down, and just barely held together, and in their ramshackle state they invite a pathos, a whisper of tragedy. Though they could easily be homes by the appearance of woods sheds, here prodding that they are homes hints at a precarity and poverty, a life easily swept away. Modernity even promised to many of its dreamers a promise of relief from poverty and deprivation. And the conditions of many have improved, but too many have been left behind.

Where and what is Utopia? Could it be, Thomas More’s “no-place”, a perfection that’s interchangeable with dystopia? An ideal always reached for but never reached. Where your loved ones wait for you. What lies ahead.

Like Thomas Wolfe says, you can’t go home again.

Our homes are not intellectual games conceived by architects, our ideas are not picked off a shelf from philosophers, the issues we fight for are shaped by our times, but we also individually shape them in our actions of support, rebellion, and apathy. We inherit things and spaces and we make them ours. Our personal lives, our lifestyles create and shape space with every meal, every caress, every picture we hang on the wall.

Bachelard says somewhere in The Poetics of Space that the architecture of your childhood home becomes the architecture for your unconscious. I haven’t lived there since I left at as a teenager. Instead, it lives in me. My last home sat in the neighborhood were my father was a child, where my child was a child. I was evicted and it was torn down to make condos for young professionals. If this is the architecture of my child’s unconscious as Bachelard says, what does it mean when that’s being destroyed by economic forces beyond our control?

Books and art and spice and ceramics and furniture. A small sanctuary to share with those I care about. A sanctuary I made with them. A place to work in peace. A room of my own. A room with a view. I can make another.

Carmen Argote slit the carpet from her childhood home in 720 Sq. Ft. Household Mutations — Part B, 2010, here the necessity of a living space contrasts with the vastness of the gallery that inhabits it. A sense of home that dropped into this grand room feels humble and true.

Somewhere beneath all this is the question of what unites these works beyond the simple geography of Latin America or having originally come from there. Shared histories can be easily pointed out both politically and aesthetically, but perhaps what makes this show really daring in its way is that it doesn’t attempt to too easily reduce a wild array of viewpoints into a narrow, closed notion of place, rather it opens it up. The idea of home, both simple and universal, steady and precarious, gives enough of what’s at stake for these artists to feel expansive in the best way.

It is not always where and from where we make our homes, but who we are and how we wish to make them.

All the rest is no less important even if it’s incidental.

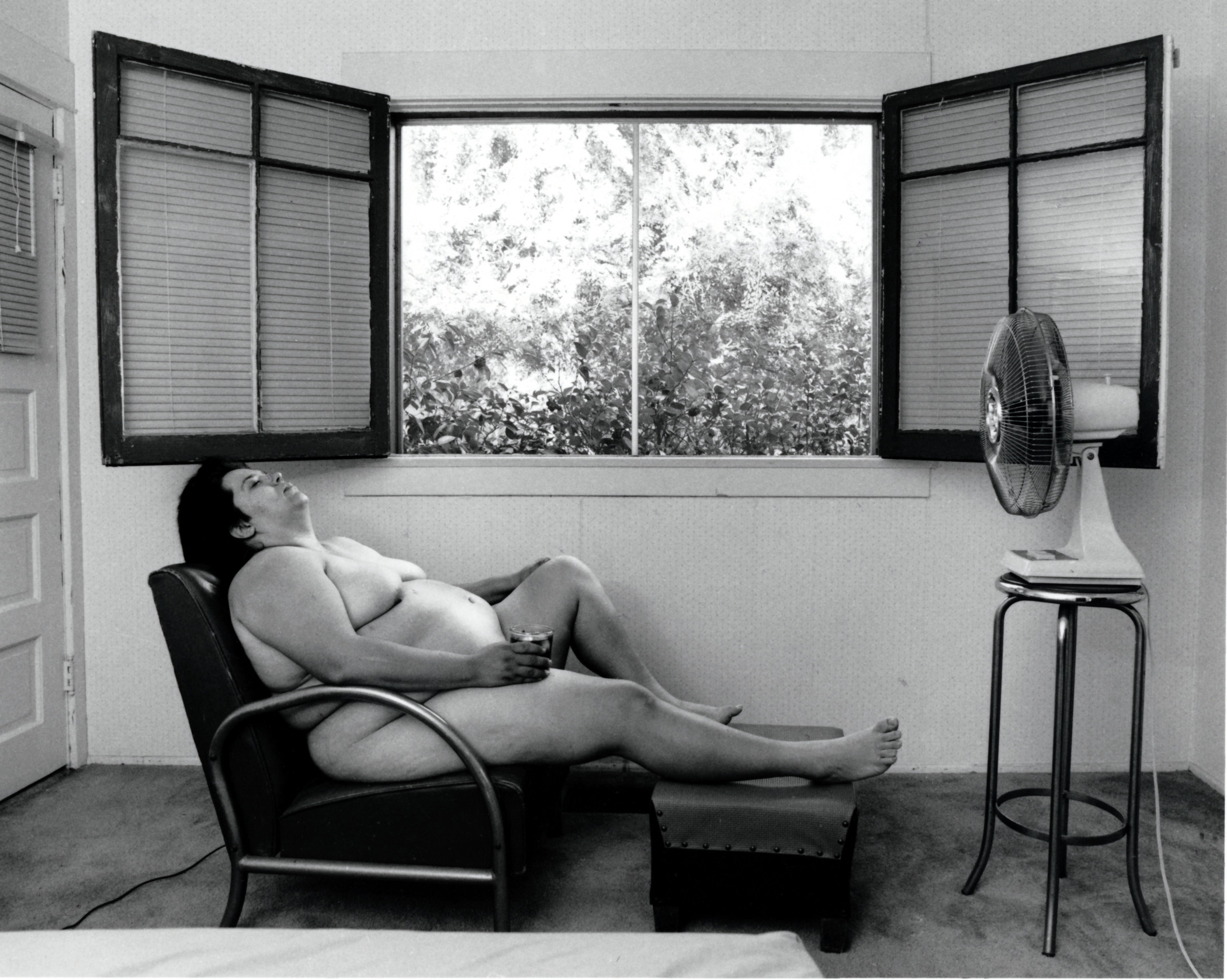

My favorite image of the show comes from Laura Aguilar in In Sandy’s Room, 1989. A voluptuous naked women, leans in a vinyl chair framed by a double open window as she nods off in front of a fan, a beverage in hand. Underneath all the heavy politics of displacement and migration, precarity and poverty, terrorists and Martha Stewart, home is really where we can take off our clothes, get loose, and chill. Not Utopia perhaps, but close enough.

Andrew Berardini is an American writer known for his work as a visual art critic and curator in Los Angeles. Berardini works primarily between genres, which he describes as “quasi-essayistic prose poems on art and other vaguely lusty subjects.”

* The exhibition is now on tour, currently at The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston through January 21, 2018

[1] Song by Harry ‘Haywire’ McClintock.

Comments

There are no coments available.