23.01.2021

As the United States’ identity crisis is currently at another peak with the Black Lives Matter movement, the pandemic, and the recent Senate and Presidential elections (and their ramifications), art and art organizations have become more critical than ever as spaces for critique, dialogue and reimagining.

“The Civil War Never Ended.”

“The Civil War Was Nothing But A Family Dispute.”

“The United States has always had an identity crisis.”

These statements are all ideas that I have expressed or heard in some form or fashion throughout my life. At the heart of them all is the idea that the United States has never truly embodied its foundational ideals.

On the opposite end of this spectrum one could see or hear the following statements:

“The United States is the greatest country on earth.”

“America is the land of freedom and opportunity.”

“Everyone can achieve the American Dream.”

These statements have been more popular than the aforementioned and promoted fervently throughout the overwhelming majority of the United States’ history. Despite the inaccuracies within them being always apparent to marginalized groups, social movements and increased access to information over the last several decades has made the fallacies more apparent to the masses. While the country’s Declaration of Independence references the holding of “truths” to be “self-evident,” these “truths” have always been in question. The most evident truth within the six statements above is arguably the one referencing the United States’ identity crisis – a crisis that can be traced back to the discussions during the nation’s founding and which peaked toward the end of the 19th century.

According to research conducted by Daniel Immerwhar, Northwestern University Professor and author of How To Hide An Empire: A History of The Greater United States, prior to 1898 United States citizens were extremely defensive and critical against of anyone who would refer to the nation as “America” instead of the “United States.” While “America” is now often the more frequently used name, this definitive moniker shift was apparently the result of the United States declaring war on Spain in 1898. This was the United States’ first overseas war at that point and parts of it would involve sending troops to aid revolutionaries in the Philippines who were also fighting against Spain.

After defeating Spain, the United States purchased the Philippines from them for $20 million and went on to wage war on the same Filipino revolutionaries they were assisting in what would become the Philippine-American War. This contradictory decision, along with the seizure of other territories such as Guam and Puerto Rico, spawned the realization among United States citizens and leaders that the country was much more of an “empire” than a “republic” or “union” of states. It was around this point that the usage of “America” became the norm – and according to Immerwhar this was led by then-President Theodore Roosevelt who was an ardent imperialist and used “America” in public discourse more in a two week period than all Presidents before him combined. When hearing Make America What America Must Become, I can’t help but think about the actual name(s) of the country and these types of histories that come along with it.

The exhibition’s title is inspired by a line from a 1962 letter written by James Baldwin to his nephew in which Baldwin refers to a “chorus of innocents” who are “trapped in a history which they do not understand” and thus unknowingly perpetuating oppression through their lack of awareness. This same population of people is one that Martin Luther King, Jr. referred to in his letters from a Birmingham jail in 1963 when he references his disappointment with the “white moderate” – individuals who are in agreement with the goals of civil rights and social justice but who are in disagreement with the methods and “radicalism” that take place within these movements. In this letter, King cites that these types of individuals are more of a “stumbling block” toward justice than “the Klu Klux Klanner.”

As the United States’ identity crisis is currently at another peak with the Black Lives Matter movement, the pandemic, and the recent Senate and Presidential elections (and their ramifications), art and art organizations have become more critical than ever as spaces for critique, dialogue and reimagining. The Make America What America Must Become exhibition is a physical (and now virtual) representation of these needs and intentions which emphasize the necessity of reflection in regards to what the country’s future could look like considering its past and present.

The 34 artists in the exhibition represent five different states throughout the Gulf South and together illuminate the truths of a country that has struggled with its understanding of that word since its founding. Prior to walking through the gallery doors, viewers are appropriately presented with artist Jeffrey Darensbourg’s video piece entitled Hoktiwe: Two Poems In Ishakkoy. Darensbourg is an enrolled member of the Atakapa-Ishak Nation, and has led extensive work regarding the narratives of Indigenous peoples in the Louisiana region. As the first piece of the exhibition that viewers are able to experience, Darensbourg’s piece prompts the assessment of one’s relationship to the truth behind the land they are currently walking upon – which prior to colonization was known as “Bulbancha” (a Choctaw word meaning “the place of other languages”). Its placement is a grounding acknowledgment of New Orleans’ pre-colonial history in addition to an emphatic point of entry and preparation for the rest of the exhibition.

Upon entry into the gallery, the topics of artificial intelligence, immigration, and political dissonance can be immediately explored through the first few works. Pieces such as Caroline Sinders’ Feminist Data Set and Annie LaurieErickson’s User Agreement create a conversation between the data we are able to create and collect ourselves as an act of protest (Sinders) versus the data we give up to large tech corporations like Google for access to basic digital features (LaurieErickson). Similar questions of agency can be segued to works in the same immediate vicinity from artists Luis Cruz Azaceta and Gabrielle Garcia Steib. Azaceta’s abstract companion works Crisis 2 and Light At The End of The Abyss contemplate the experiences of escaping exile while still being spiritually attached to the country one is leaving – while Garcia Steib’s video piece located on the same wall uses field recordings and archival footage to highlight the narrative of a Honduran immigrant experiencing oppressive violence during her migration to New Orleans. As a country that was founded by European immigrants, the historical and current experiences of other immigrants in the United States is one of the most central components of its identity crisis. The presentation of these narratives this early in the exhibition prepares viewers for the prominence of these themes throughout the rest of the space.

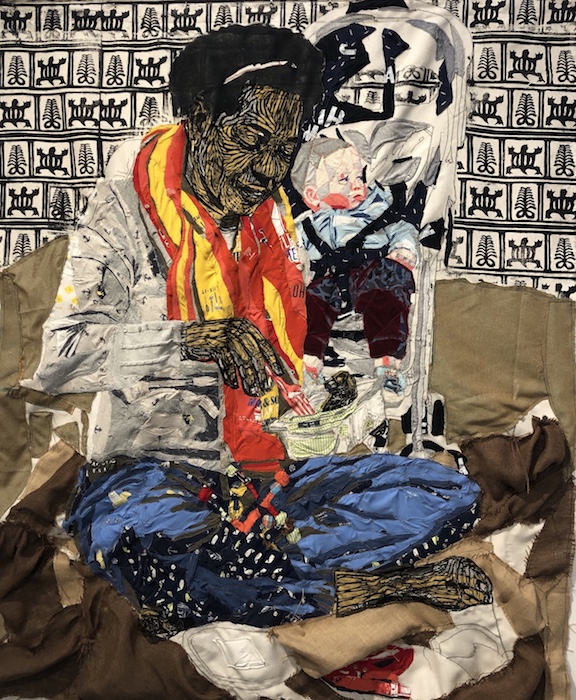

Toward the “middle” of the exhibition layout, a work by Krstyle Lemonias’ radiates along a wall of four fabric-based works. Her piece, entitled Yuh no see say Him Hungry, is able to encapsulate so many of the exhibition’s themes through its references, imagery, and even method of construction. The main subject within the piece is Lemonias’ mother and it is a part of a series that explores the complex experiences of Caribbean women’s labor in the United States. Through the quilting of baby clothes gathered from children that her mother cares for, Lemonias is able to use this technique, which has been so integral to the expression and survival of Black people in the United States, to emphasize the ways that the labor of Black women has and continues to be taken advantage of. The economic inequities that continue to occur between these women and the often white families that they work for is a dichotomy that has deep linkages to slavery in the United States.

One of the last pieces of the exhibition is another that highlights the experience of immigrants but in arguably the most necessary and engaging way of any piece within the space. Cartografia Del Camino/Map of Detention Centers is a collaborative installation by artists Savannah Levin, Lacy Levin, Nelle Edge, Caitlin, Natalia Roa, Elias Serhan, and Antonia Zennaro. The piece features an embroidered map that identifies jails, prisons and I.C.E operated detention centers in an effort to raise awareness about the injustices experienced by individuals attempting to enter the United States. In addition to referencing the map, viewers have the option to pick from four different phones to listen to recordings of individuals who have engaged with these facilities in different ways such as through seeking asylum or surviving a detention center. While the piece’s ability to engage viewers, particularly around these specific issues is exceedingly important, the nature of the artists’ backgrounds is potentially even more integral to “what America must become.” The fact that at least several of the artists in this collaboration identify as white is a testament to the need for more white individuals—particularly those of European descent—in giving their energies to the renovation of a country that was built with cracks in its foundation. These cracks have manifested into what is most widely referred to as “systemic racism” and its ramifications can be seen in nearly every sector of human endeavor within the United States. As a country that became the largest economy in the world through the mutilation and oppression of Indigenous and Black bodies on stolen land, the reality that the value for these bodies must still be petitioned through acts of public protest becomes less surprising.

Part of the reason the United States has gotten to this point of intense contention is the fact that so many of these topics have been ignored by those who identify as white—a privilege that has become an additional tool of violence against communities of color. Even when these issues have not been ignored, they have never received the attention needed for change within white communities. The United States will overcome its identity issues and become what it “must become” only when the energy and volume from these communities are as high or higher than it has been from those communities that have been oppressed and shouting for centuries. As a country that until this point has been built upon the devaluation of Black, Indigenous, and persons of color bodies, it will only become what it “must become” when these same bodies are given the freedom to truly dream and thrive. The exhibition collectively provides viewers with an entry point into the necessity of these types of narratives and adequately affirms art’s perpetual ability to imagine a future that might not always be as easy to see.

Make America What America Must Become

Curated by George Scheer, Katrina Neumann, and Toccarra A. H. Thomas

Contemporary Art Center, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA

Friday, September 18, 2020 to Sunday, April 25, 2021

More info here.

Comments

There are no coments available.