31.05.2018

By Diego Del Valle Ríos, Santiago, Chile

May 10, 2018 – May 13, 2018

There is movement in Chile: migrants, mainly Venezuelan, Colombian, and Haitian who puncture and enrich the apparent whiteness of Santiago; feminist students who march and demand of their university faculties an education free of sexism and machismo; demand a curricular and administrative restructuration that considers a critical feminist perspective as an fundamental part of the spaces of study and critical thinking. There is movement from the resistance against the cooptation of neoliberalism from a centrist and conservative government that, after four years of wearing the mask of the left, now dons a right-wing mask. There is movement in art itself that remains dynamic, mainly among the young, despite a public cultural system that returns to the sluggishness of bureaucracy, accompanied by a system of cultural media that seems to move away from critical discourse to avoid bothering the modest political and cultural elite on which they depend.

In Chile there is an academic, intellectual, and artistic power that again is gaining traction through collaboration and the articulation of networks. The first impression is that this is a consequence of migration, both as a result of the reconfiguration of regional populations due to political-economic crises, such as those in Venezuela and Haiti, as well as of the return of second- and third-generation descendants of exiled families to their native countries, a movement motivated by a renewed interest in their roots and identity history. The exhibition Cambio de lugar [Change of Place] at La Moneda Cultural Center, organized by the Oficina Mo-Ma (Mariagrazia Muscatello and Monstaserrat Rojas Corradi) confirmed this hypothesis by shedding light on the characteristics that define the current wave of migration in Chile. Through the photographic work of eight artists, the exhibition opens an interrogation of the perception of migration, allowing for the recognition of the specific circumstances and characteristics of the displacement of these populations that have arrived in Chile in recent years. The exhibition is an urgent conversation that must extend both inside and outside our respective contexts to help us to understand the present-future that is rapidly unfolding on the planet: a present-future that is inevitably characterized by the destabilization of populations by processes of migration.

It was tourist migration that allowed me to spend a week in Chile for Gallery Weekend, a program organized by Víctor Leyton and Juan Pablo Vergara in collaboration with SÍSMICA, an independent body created through the Association of Contemporary Art Galleries (AGAC) with ProChile, an agency linked to the Ministry of Foreign Relations that seeks to promote Chilean culture abroad. The second edition of Gallery Weekend Santiago was held from May 10 to 13, and its program sought to articulate the circuit of galleries in the nation’s capital with the aim of broadening their public and strengthening their relations with collectors and national and international art agents. “Gallery weekends” were developed as an alternative commercial strategy, one that seeks to decentralize the circulation of the public away from the rigid space of art fairs, and they are beginning to have greater traction on the South American continent, with Art Weekend São Paolo, Gallery Weekend Mexico, ArtBo Fin de Semana (Bogota), and Condo. Given the high costs of art fairs and the oversaturation of participants and activities organized around them, weekends dedicated to galleries have the advantage, on the one hand, of allowing gallery owners to take advantage of and activate their exhibition spaces without exuberant costs, and to extend out to the studios and spaces of their artists. On the other, they help to develop greater closeness between gallerists, artists, and visitors through wider circulation and more encounters. However, for these types of initiatives to function better they must move away from the accelerated rhythm that characterizes our contemporaneity. In our experience in Chile as foreign visitors organized by an agenda, we had minimal time to talk and learn more about our hosts beyond the information we received from a quick tour. Likewise, the initiative of Gallery Weekend Santiago lacked a transverse program that extended beyond the spheres of contemporary art that would have offered insight into the cultural context in which they developed. The inclusion of spaces of other cultural spheres on the Gallery Weekend maps allowed us to understand, for example, the importance of the closeness between the written word and visual art, which could be seen in such spaces as the library Metales Pesados or Instituto Tele Arte, to mention only a few.

Although the galleries are the center of this type of commercial program, it is necessary to think about how to avoid their being understood as separate from the country’s historical burden in relation to its cultural development, of which these galleries are an important element. If the intention is to project the circuit of Chilean galleries internationally, it is necessary to ensure that foreign visitors understand the role gallery owners play within the context.

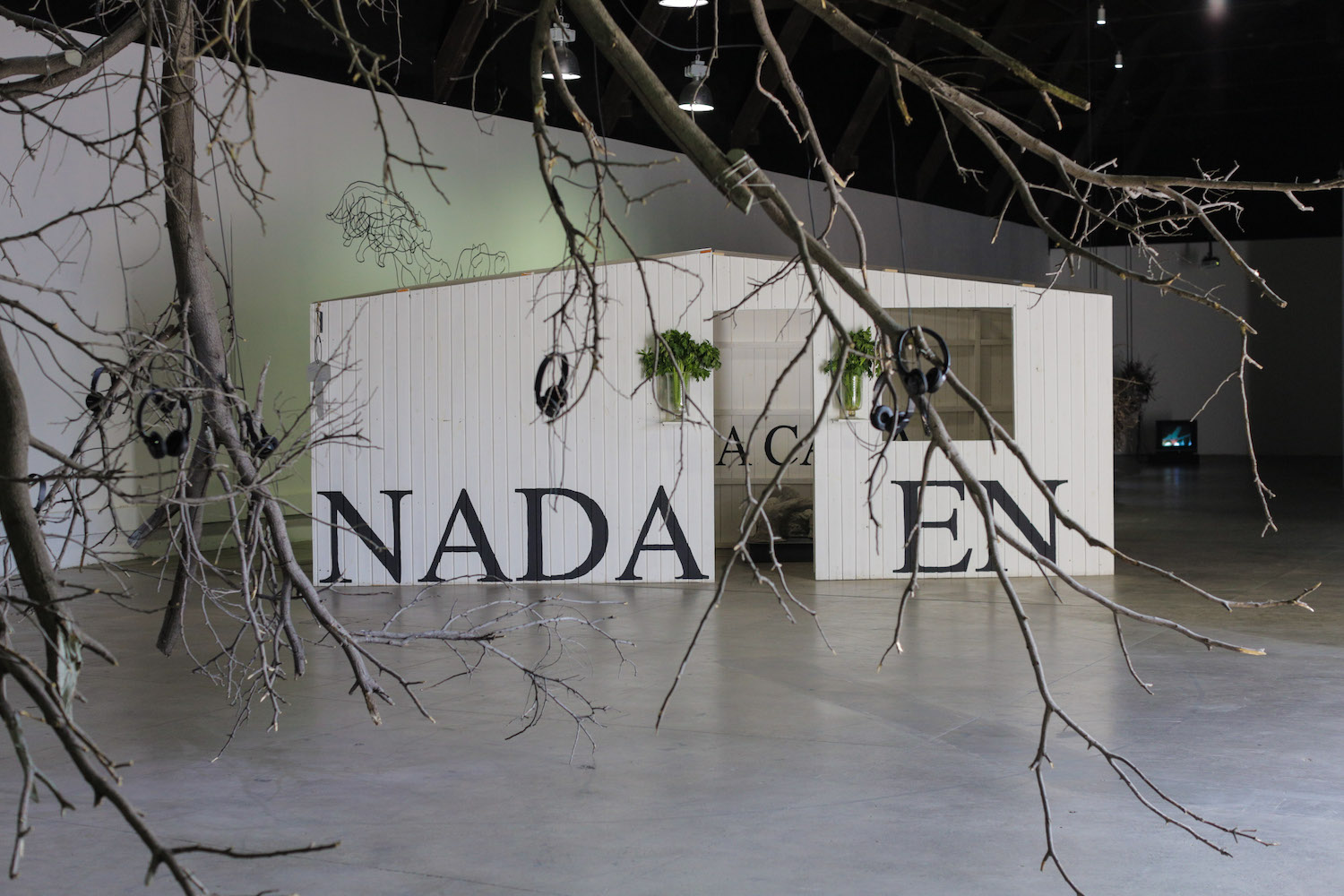

In her essay in the book Copiar el Edén, the artist Catalina Mena describes that moment in the Chilean art scene in the early and middle 2000s that grew out of a desire for connection, the desire to meet the Other through the diversification of the languages, codes, and objects that passed through the individual and collective body in the context of mass consumption. This multiplicity found in the body a means to reconnect with its surroundings and thus a means to resignify the notion of the domestic in relation to a reappropriation of public space as a common and everyday space. This reflection on the visual can be seen in its collective historical dimension in the exhibition Hoffman’s House in the Matucana100 cultural center, and likewise, on an individual level, in the work of Juvenal Barría presented at Croxatto Gallery.

The exhibition Hoffman´s House, los nuevos sensibles condenses the story of a large group of artists who experienced the disorientation of the nineties post-dictatorship era and who happened to meet along the walls of the itinerant independent space Hoffman’s House—founded by Rodrigo Vergara and José Pablo Díaz—, where the exhibition of emerging works questioned cultural and academic structured, and valued self-management and autonomous artistic production. By bringing this apparent past to the present, the exhibition allows us to discover the genealogy of contemporary Chilean art from the emotional bond that continues to motivate it.

On the other hand, in his exhibition INFILTRADX, Juvenal Barría resorts to transvestism to personify the alter ego, La Nana [The Nanny]. The main body of work comprises an intervention into tourist portrait slides of a high-class lady that the artist found in an antique market. Barría inserts the image of La Nana—who surely accompanied that patroness from the shadows—into the photograph. In doing so, Barría places into conflict notions of class and gender that classify coexistence and the value of bodies in everyday life. Barría questions where we direct our gaze and persuades us to critically recognize the reality of everyday life beyond the hegemonic mirage of the individualized image.

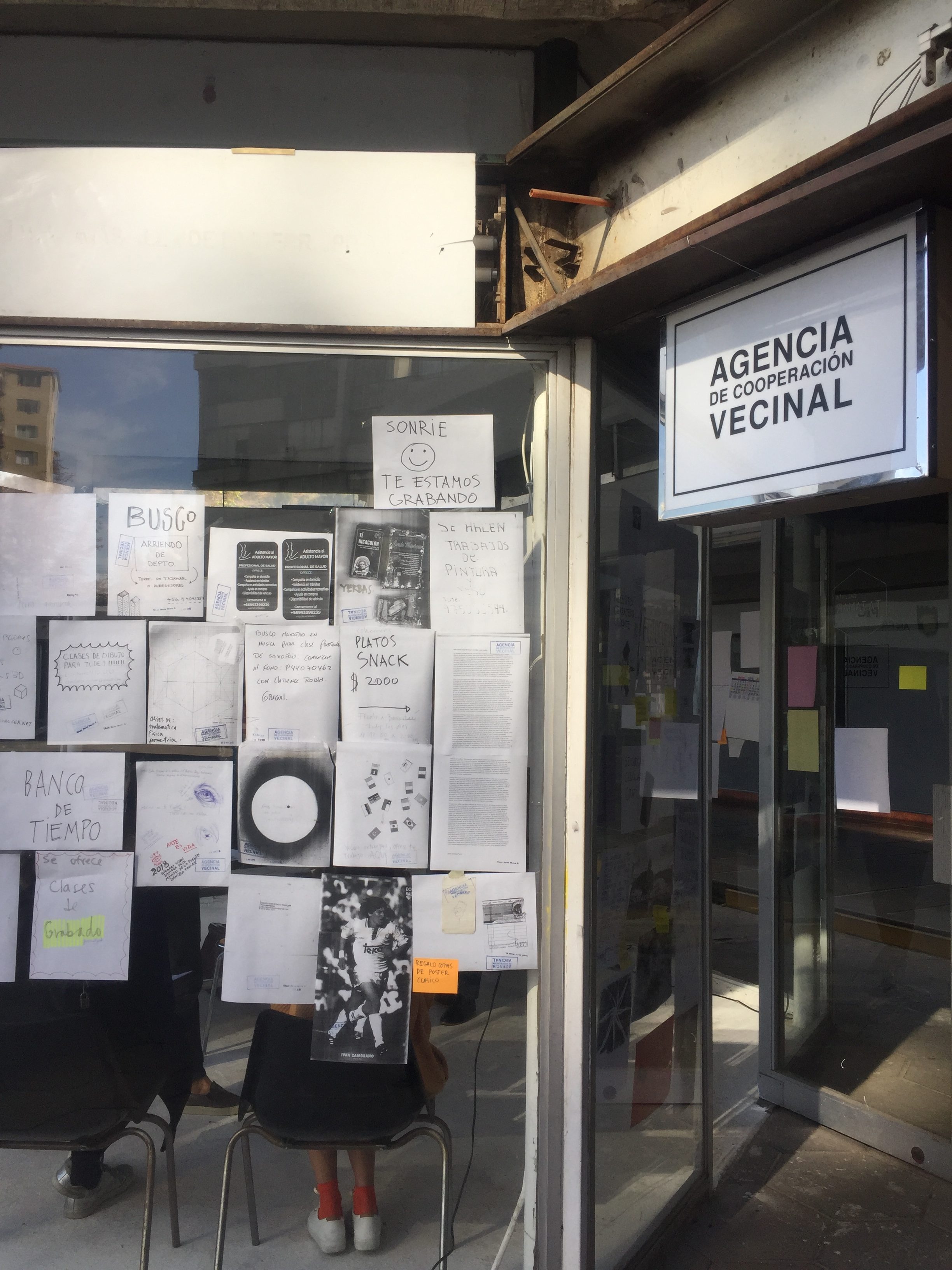

This same persuasion is found in Agencia de cooperación vecinal [Neighborhood Cooperation Agency] activated by Diego Santamaria in Galería Tajamar. The office, installed in the 59th Hexagonal Shop of the Tajamar Towers housing complex, seeks to provide a tracking and supply service of the professions, tasks, and knowledge performed by the neighbors. Santamaria directs our attention to the voids of the fractured community created by the social architectural system of the Tajamar Towers, which is itself a result of systemic individualization, in order to fill it with the daily movements of an articulated community. Receiving people, meeting them, making copies, pasting them, social services: the movement that maintains the space in relation to their environment offers a possibility to create networks and reduce the distance between us and those around us.

Projecting Mena’s reflection ten years ahead, one can also find an artistic scene in Chile that moves away from the body and instead concentrates on the object as an extension of the body, questioning the heritage of the artistic traditions of painting, sculpture, and the ready-made. This can be observed in the exhibition Dialéctica menor [Minor Dialectic] at Sagrada Mercancía, where the materiality of the medium and the concept of the piece are brought together to question aesthetic dimensions and their political possibility from formal and plastic characteristics. The exhibition includes work by Adolfo Bimer, Jessica Briceño, Santiago Cancino, Víctor Flores, Sofía de Grenade, Alejandro Leonhardt, Adolfo Martínez, and Matías Solar, all founders of Sagrada Mercancía. Throughout its existence, Sagrada Mercancía has provided an exhibition space for emerging artists who work within an experimental and reflexive-visual approach. Reviewing the exhibitions that they have hosted reveals an emphasis on discussions and discourses related to artistic production on materiality, the body, and space. In Sagrada Mercancía, as in any space run by artists, the common makes possible an affective network for the free exploration of artistic ideas in consonance with the fact of sharing and maintaining an independent space.

Grace Weinrib also explores the same conservative artistic tradition questioned in the show at Sagrada Mercancía in her exhibition La isla de los calcetines [The Island of Socks]. Exhibited in Die Ecke (one of the most important galleries in Chile that developed throughout the 2000s), the exhibition playfully brings together a series of collages that dislocate the traditional rigor of painting and drawing through color. Weinrib starts from a personal anecdote that occurred in a moment of much socio-cultural movement to reflect on the possibility of liberating and making flexible artistic practice beyond the conservative limits of hegemony, reminding us that resistance and dissidence is, above all, personal and playful.

The conservative academic tradition is again questioned in the work of Fernando Portal presented at Galería NAC. Bienes Públicos [Public Goods] recreates a series of consumer goods—from appliances to furniture—that were designed by the Design Group of the Technological Research Committee of Chile (INTEC) between 1971 and 1973. The group, with support from the socialist government of Salvador Allende, had the task of developing industrial design to support national growth. Their work was interrupted by the coup d’état, and as a result their archive of socially-focused prototypes and design methodologies was mostly destroyed. By recovering the limited set of drawings, archives, and prototypes, and recreating the objects designed by INTEC, Portal opens up questions about academic historicization, the activation and exhibition of archives, as well as the trans-disciplinary possibilities for the rescue and reconstruction of memory conceptual art offers.

In Chile, there is constant movement that must be closely followed. Meanwhile, the arts adapt and take advantage of this oscillation to expand and reinforce their connections based in a historical burden that reminds us that the desire to be with the Other is the only way to stay active.

Comments

There are no coments available.