11.03.2016

by Ricardo Pohlenz

February 24, 2016 – March 6, 2016

FICUNAM 2016: FICTION AS REALITY’S WAY OUT

By Ricardo Pohlenz

Once you assess the range of films that the festival’s director, Eva Sangiorgi, has programmed in collaboration with Roger Koza and Sebástien Blayac, two selections turn out to be quite significant. One is the short film entitled The Glory of Filmmaking in Portugal (A glória de fazer cinema em Portugal), by Manuel Mozos, which speculates on the limits of invention with regard to cinema’s origins in Portugal. The second is Visit or Memories and Confessions (Visita ou memórias e confissões), the film Manoel de Oliveira made in 1982, when he had to sell the house he’d lived in for forty years, to pay off debts incurred making films as well as due to the mismanagement of a factory he inherited. Beyond the fact that these two films serve as a prelude to certain particularities in Portuguese cinema—particularities that discover a kind of purification in work by Miguel Gomes, who was the subject of a festival retrospective—they both reside somewhere between documentary and fiction and posit an initial question on the possibility that a clear separation between the two truly exists, above all with regard to productions outside the commercial circuit that in themselves suppose an exploration of their own form- and content-related borders. The films also posit an exploration of these genres’ scope as instruments that not only capture, frame by frame, what they find before them (or what they seek to find before them), but also reflect—from a place of the medium’s very limitations—on everything that remains outside of frame in relation to what is framed. Contaminación—i.e., “pollution; contamination”—was the word Eva Sangiorgi used during the awards ceremony to synthesize the essence of what the festival was. In a moment of industry crisis—a moment that clings to a Nietzschean eternal-return that maintains the same contents and formulae, recycled time and again, will continue to nourish it—the UNAM festival presents to the degree possible those productions that otherwise would not reach theatres. In his own films, Miguel Gomes has evinced a vocation for inventing reality. His trilogy, presented at Cannes Directors Fortnight 2015 and entitled Arabian Nights (As mil e uma noites), is a cogent example. In it, he sublimates Lisbon’s day-to-day joys and miseries by lending a voice to Scheherazade in titles over black-screen that—mixed in with the action—describe and transform her. Much of the fun in Gomes’s films is an unfinished, almost abstract sensation whose counterweight is a narration that occurs in silence and describes what ought to be on screen. Between music, background noises and birdcalls, the soundtrack also does its part. Not unrelated to this, a great deal of the trilogy’s third film is given over to the habits and customs of Lisbon bird-sellers who trap chaffinches and goldfinches whom they enter into an annual birdsongs contest which turns out—at least at first—to be as anodyne as it is fascinating. Strictly speaking, this material cannot be said to be a documentary on bird-sellers. As captured by the lens of director of photography Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, the vendors become characters responding to the needs of the narrative. Obedient to the story—and the fatalism that goes with it—they positively shine with the knowledge their misadventures are not true, tantalized by the idea that the reality they’ve been stripped of by appearing on camera might reach them or overtake them. The screen takes the place of the mirror: it inverts it, turns it on its head, negates anything more than light and affirms its spectral status.

When Visit or Memories and Confessions (1982) is brought out of hiding and screened, Manoel de Oliveira knows an apparition when he frames it. Aware the film wouldn’t be seen until after his death, its reality becomes relative. He knows he’s separating himself from that particular moment—when he was seventy-four and with quite a bit more time to live—as he speaks on screen with the always illusory, always apparent certainty that time will pass. Despite the truth of what the film declares, it is not a document in the strictest sense, since it permits an even greater non-reality by adding a pair of off-screen voices to the soundtrack that encroach on the movements the camera takes through various rooms. After the screening, editor Sofía Ochoa commented that to a great degree what Oliveira had done in this film—speaking of himself and of his bad breaks, or happenstance or whatever—is now something everyone does, thanks to everyday technologies. Ultimately what she said was that Oliveira had made the equivalent of what today would be a videoblog. I suppose she’s right, given the distances and considering—metaphorically—than every multiplication of the loaves and fishes is a banality.

It was another Portuguese director, João Nicolau (who has collaborated with Miguel Gomes), who fashioned an elegy of the banal with his John From (2015), a film of great formal rigor in which, with some freshness, he combines the commonplaces of the adolescent idyll with the postcolonial charm of southern exoticism. John From received a special jury mention. A whole other level of banality and dead time is found in the material that Iraqi director Abbas Fadhel recorded in 2003, just before the US invasion and following the downfall of Saddam Hussein, with which he put together Homeland (Iraq, Year Zero), from 2015, a two-part production that documents daily life in Baghdad through the dead time the Fadhel family shares (or represents). It juxtaposes, for example, the closed circle in which the family lives when faced with the threat of invasion, messianic representations of Saddam Hussein that musically scored television commercials present (and whose lyrics are as terrifying as they are ridiculous) and the camera that ventures onto the streets after the city’s liberation, lending a countenance and a voice to people very different from those George Bush, Jr. put over as the enemies of the free world. Homeland (Iraq, Year Zero) walked off with the Audience Prize. Young Chinese filmmaker Bi Gan received Best Director for his first-ever production, Kaili Blues, (2015), a mind-blowing trip into “deep” China in which he plays with notions of time and space, including one delirious take that lasts longer than 30 minutes.

The International Prize winner was One Floor Below (Un etaj mai jos; 2015), by Rumanian filmmaker Radu Munteane, who—according to Roger Koza and among other signatures—is characterized by his “masterful use of the off-screen.” Curator Haden Guest, filmmaker and artist Phillippe Grandioux, artist-curator Guillermo Santamarina, critic Alexandra Zawia and filmmaker Lois Patiño comprised the jury. Patiño presented his short film Night Without Distance (Noite sem distância; 2015) as part of the “Porvenir” (i.e., “future”) program. In it, the Gerês Mountains smuggling route between Spain and Portugal becomes a spectral tableau whose colors are reversed in the final print, creating an object-related sensation on the screen.

There were also retrospectives showcasing Marlen Khutsiev, a representative of what was called “the Soviet New Wave,” as well as work by Mexico’s Leobardo López Aretche, who directed 1968’s The Scream (El grito). US director Thom Andersen presented The Thoughts That Once We Had (2015), an essay film that explores and revises concepts Deleuze laid out in his two volumes on cinema.

In a conversation with the audience, Andersen remembers that listening to a rudimentary recording he made of the soundtrack from Howard Hawks’s To Have and Have Not (1944) led him to become a filmmaker. Also with regard to relationships of politicization and objects raised to fetishistic extremes, British filmmaker and visual artist Isaac Julien was present in body, oeuvre and omission at a MUAC showing of his theatrical films and a sampling of his general production. In dialogue with the audience, Julian dismissed the idea that there remains a path forward for cinema’s conventional formulae, made pronouncements on the limits of the digital as medium and archive material, and anticipated the (at least immediate) future by announcing that Kodak would be once again putting its Super-8 format on then market.

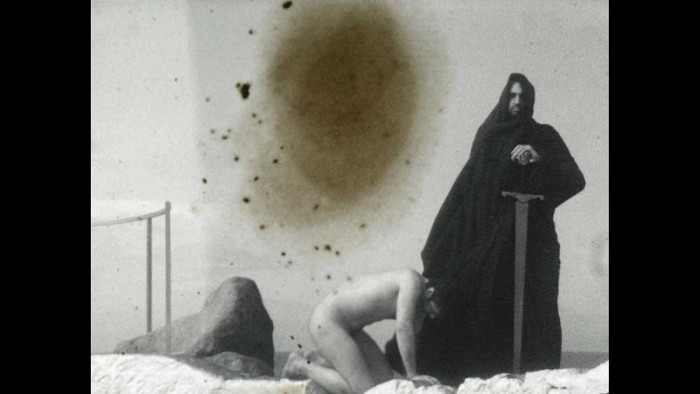

Alongside Andrea Bussman, Nicolás Pereda presented Tales of Two That Dreamt (Historias de dos que soñaron; 2016) a film that literally transpires off-screen. Andrea Bussman set out to capture the downtime on a Pereda shoot with a Roma family in Toronto, loosely based on Kafka’s Metamorphosis. The visual itinerary the filmmakers present follows the family during the shoot’s downtime, creating a dual fiction between what is said and what happens elsewhere. This turns out to be significant, above all to the degree that the serendipity of accident on top of intention, as well as a finality that ends up creating the illusion of a reality that the mass media have irremediably relativized, all coincide in the mechanisms that lead to the final cut. Truth stays far out of reach in these artworks, but an illusion of the truth is created within what can be described as “premeditated candor.” Nicolás Pereda won the National Prize with another film, Minotaur (Minotauro; 2015), an ambitious interiors-only “staging” that from its very title insists on the sense of shock and awe that Mexican cinema—as an extension of its narrative—has always held when it comes to Greek tragedy.

Comments

There are no coments available.