02.03.2022

EXTRACT is an online section where we share some of the texts published by Temblores Publicaciones, Terremoto’s publishing house. We present the seventh extract of this section, “Always Elsewhere,” by Gerald Raymond McMaster, from “Swap Meet”, published on the occasion of the exhibition “Brad Kahlhamer: Swap Meet”, presented at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art (SMoCA) in Phoenix, Arizona. This project is born from the artist’s experience in swap meets, spaces of reciprocity and barter that trigger encounters where (self)recognition allows for the generation of community.

Always Elsewhere by Gerald Raymond McMaster

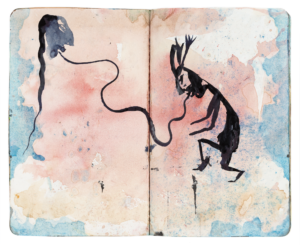

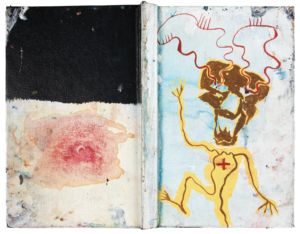

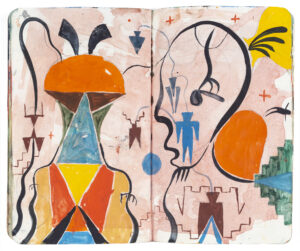

For those unfamiliar with the genre of ledger art, it is made up of drawings done by Indigenous warrior-artists from the Northern and Southern Plains of the contiguous United States of America and Canada from the mid-nineteenth to early twentieth century. Rendered using disused accountant ledgers, the medium was quickly picked up by men who saw how it could provide affordance to their schemes. Such drawings were understood by them to express truthful representations of their adventures and achievements. The stories were not just depictions in ledger books, they were records that elevated the status of a warrior amongst his comrades, especially those he needed to corroborate the story. In other words, veracity was paramount. In Kahlhamer’s drawings, however, he records adventures of a different sort, not so much to document an external event, but rather to mark his quest for the truth of his situatedness in relation to questions of being. Looking over his drawings and sketchbooks—what he calls his Nomadic Studio—we are brought into a very private space. The drawings appear almost as “notes to self” and, in a way, seem to free him up as an artist to write, to draw, and to note, without a thought of making visual blunders. Within this medium he is free to roam.

Indigenous identity has not always been clear. In the last half of the twentieth century many have been exposed as non-Indigenous and thus censure of their work has occurred. It is the metonymic “tribal card”—the proof of status, a tribal membership—that has for several decades been the means to a sense of identification with Indigenous heritage. The challenge for Kahlhamer and thousands like him, who were adopted out of their Indigenous home communities, is to seek verification of one’s membership with either a state or federally recognized tribe. Sometimes it takes art to bring clarity to the complex realities of one’s ontology, especially the cultural genocide inflicted on Indigenous people. At the same time, the governments who created the conditions further authorized private organizations, such as religious organizations and adoption agencies, to remove children from their homes and communities with little to no legal repercussions. In time, authority over making decisions on tribal membership was eventually passed to Indigenous communities.

Likewise, the Indigenous art market has long been an arena where the trade in works has been difficult to police, so much so that in 1990 a US law was passed that focused on the individual, making it illegal for them to identify as an American Indian artisan unless they were members of a state or federally recognized tribe. There is, however, some obfuscation within the act as it refers to “artisans” and not artists. This difference is significant because the category “artist” was drawn into the debate, which led to some individuals being called out because they could not prove their Indigenous heritage. While different communities have views or policies on the matter, the culture industry—art, craft, music, theater, and literature—seem to be most inclined to take the issue into the public forum. With decades and decades of this imbroglio, the effects upon so many individuals have no doubt been psychologically disheartening.

Kahlhamer has never hidden the fact that he was adopted out to the Lutheran Church, a process prompted by the federal government, which not only guaranteed immediate assimilation but Christianization as well. In the United States on average there are 140,000 children adopted each year. In 1969, New York attorney Bertram Hirsch collected nationwide data on the percentage of American Indian children placed in adoptive homes, foster homes, and institutions. He discovered that through the Indian Adoption Project, from 1958–1967, an astounding 25 to 35 percent of children were adopted out of Indigenous communities, of which 90 percent were sent to non-Indigenous families. It was not until the late 1970s when Indigenous authorities were able to assert control of these longstanding practices.

The difficulty in acquiring the proof of authenticity that pervades the Native American art landscape as expressed in the Arts and Crafts Act, which sets out clear boundaries and specific rules, is precarious at the best of times. The identity politics of the Indian market feeds into notions of “legitimacy” and the Western colonial perspective that created a structure of inequality: You may look and talk like us, but you are not one of us. Social psychologist Dolly Chugh recently wrote: “. . . the society in which we live is structured around [specific] identities. Those whose identities do not vary from the norm are lulled into thinking that their experience is universal. People with other identities are reminded of their difference from the norm on a regular basis.”#1

An exhibition such as this seems to create its own community, like the swap meet, which exists outside of typical formal regulations and enters into creative capacity-building between like-minded strangers and friends who seek out similar truths of belonging. In these places, identities of the human and more-than-human are the subject of profound change, making manifest a third space of in-between alterity, subject to relations with the land.

Find this full text in the printed version of Brad Kahlhamer: Swap Meet here.

Dolly Chugh, The Person You Mean to Be: How Good People Fight Bias (New York: Harper Business, 2018), 112.

Comments

There are no coments available.