03.08.2017

By Alexia Veytia-Rubio, Los Angeles, California, USA

April 22, 2017 – July 22, 2017

In the exhibition entitled A Decolonial Atlas: Strategies of Contemporary Art in the Americas, we encounter the questions Latin American artists face when it comes to their artistic practices’ contextualization in the contemporary environment that has historically been monopolized by notions of art based on the legacies of Occidental ideology. Curated by Pilar Tompkins-Rivas—who has been recently named Vincent Price Art Museum Director—it presents artists and various contemporary collectives from the United States and Latin America who work in disciplines ranging from painting and sculpture to photography and video. Their works take up dialogue on de-colonialization and, as a central theme, respond to questions on colonialism’s legacy as they destabilize established narratives through counter-hegemonic perspectives.

A Decolonial Atlas is subdivided into four sections called “thematic constellations”: Recasting Indigeneity, Dislodging Time, Intervening the Archive and Countering Extractivism. In this context, the term constellation references Alexander von Humboldt’s observations from his early-nineteenth-century Latin American travels. From the start of the show, relatively subtle allusions are offered up to the public regarding the arrival of European colonizers, who, from the time they made contact with the Americas’ indigenous inhabitants, have largely written accounts of the colonial conquest as well as subsequent history from their own perspectives.

We start out with Recasting Indigeneity, where (the curation tells us), the artworks’ purpose is to “subvert the exoticized gaze on indigenous cultures through the colonial lens, reaffirming native-identity formations, beliefs and practices in the contemporary context.” [1] By situating indigenous cultures’ representations more in the present than in the historical past, the artists in this section seek to counteract erroneous concepts of native cultures, historically established—in addition to by means of ethnography and anthropology—through literary and philosophical notions of so-called “romantic primitivism.” The clearest example of the issue to which this section seeks to respond are Martine Gutiérrez’s photographic pieces reflecting dynamic intersections between indigenous peoples and pop culture, as well as non-binary gender identities.

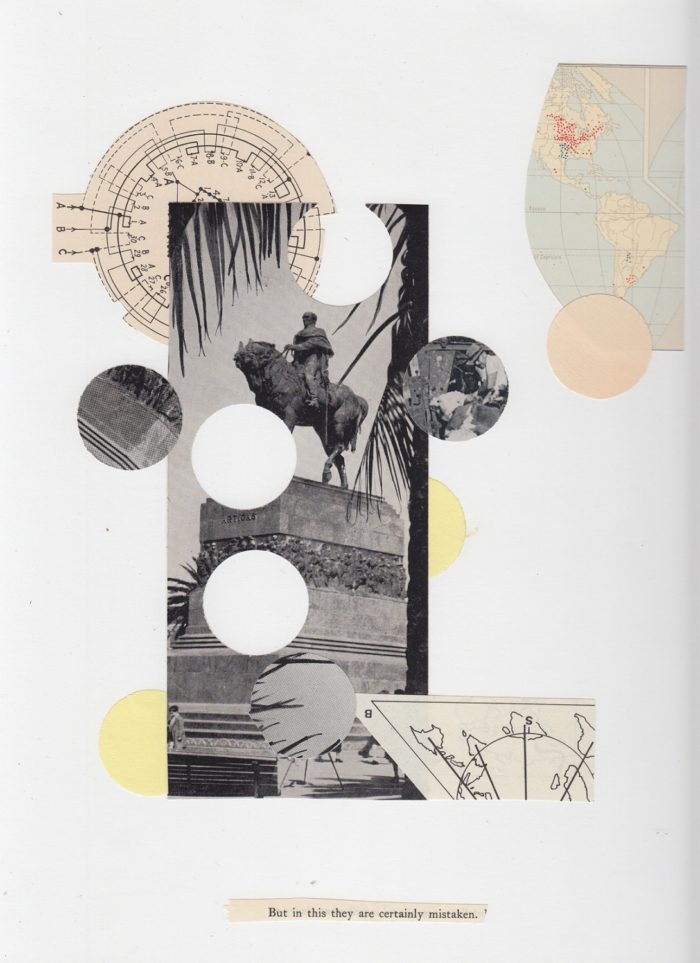

The next “constellation”—and probably the show’s least represented—is Dislodging Time, whose uniting axis is Pablo Helguera’s collage series entitled Suite Panamericana (2007). It seeks to “shatter a lineal notion of time,” reflected in images and texts that interweave location, geography and history through an intentionally disjointed focus whose intention is to articulate a “politics of place.” The works in this section allude to the cultural history of modernity established in relation to colonial and pre-Columbian periods and intentionally strike against them. A text makes brief mention of theorist Néstor García Canclini and his notion of “multi-temporal heterogeneity” as well as the simultaneous coexistence of different temporal eras. As Helguera notes, “the past is a foreign country” and “the future isn’t what it used to be.”

One of the show’s most outstanding artworks is Traveling Dust (2014), a 27-minute film projected cinema-style, by Javier Tapia and Camilo Ontiveros, Chilean and Mexican artists, respectively. Traveling Dust uses series of images captured in Chile, Mexico and Los Angeles whose intent is to portray the regions’ endemic human, economic and cultural flows. It might be that for Tapia and Ontiveiros, what mattered most was to establish a parallel between immigrants’ journeys and personal processes and the story of current Latin American artists. Traveling Dust is a small, hemispheric glance at the Americas that, despite having fallen into a highly conceptual representational model (to which we are tethered in contemporary practice and which can itself be attributed to the medium of video), the piece does open up new ways of thinking. And in spite of taking on an amalgam of highly political issues, the artists do come up with something that humanizes participants, and regions, at the same time a poetic gaze is attributed to the various places and realities of zones that are intrinsic to the artists’ geopolitical discourse.

In the third “constellation,” Countering Extractivism, artworks intervene into the anonymity of extractive economic practices—both in the public and private sectors—to bear witness to natural-resources exhaustion as a means of social control. Carolina Caycedo’s video piece entitled Spaniards Named Her Magdalena, But Natives Call Her Yuma (2013), is another one of the show’s biggest moments. In this dual-channel video, images of water flows in Colombian dams and rivers are juxtaposed with human and military flows in major cities. Caycedo has previously mentioned she conducted interviews with many of the affected individuals as well as those involved in developing that nation’s El Quiombo Dam, including activists, ecologists, opposition leaders, professors and a shaman, to be able to develop an understanding and exploration of ideas on flows and conflict. In Spaniards Named Her Magdalena, But Natives Call Her Yuma, parallels are drawn between water held back by dams, oppressive power formations and military methods for social control. Countering Extractivism questions the forces of industrialization and modernity over natural resources in areas where native peoples live. The artist reminds us of as much as she uses her own voice to whisper the flowing river’s both percussive and soothing noises.

Finally, in the fourth “constellation,” Intervening the Archive, artists like Carlos Motta seek to disrupt the conquistadors’ hegemonic power structure over the conquered in an attempt at “mocking” the colonial-era historical record (or a lack thereof) as they question doctrines of genocide and anti-native-culture discrimination in the name of colonists’ expeditions, expansions and indeed, colonialism. In Motta’s Deseos, a 2005 documentary, the overriding theme is exposing the ways the imposition of medicine, law and religion provoked the disappearance of parallel dialogue, leading to a lack of historiographical documentation and material. In a highly-unified fashion, this section’s artworks reflect contemporary research into colonialism’s legacy when it comes to the historical record.

The main—perhaps sole—problem with A Decolonial Atlas is its excessive use of video as the main medium of the show’s artist-narratives, considering the fact that making one’s way through the relatively small exhibition gallery implies visitors’ total immersion into the video series installed along its edges: sounds of traditional native music overlapping with voices in English and indigenous languages, Caycedo’s murmurings and multiple reflections from screens projecting images ranging from amusement-park carrousels to aquatic currents to South American endemic plant species. These perceptual juxtapositions, though somewhat jarring, come together as an ongoing reminder for the espectator to continue delving into the notions of space, cultures encounters, time and the constitution of history. Apart from problems related to museum-design, the videos are effectively employed as a critical tool for expanded narratives and immersive images. Coming out of the exhibition implies exiting the museum with more questions than answers. Why video as the predominating medium? Is it somehow a curatorial effort to both reinforce and de-mythologize the vision the West imposes on Latino artists? Or as Martine Gutiérrez said previously: “when they leave you confused, you have to keep on thinking.”

This ambitious exploration on Latinoamerican art comes at a moment of particular political instability in the USA and the global context. Both A Decolonial Atlas and the next initiative of the Getty Foundation PST: LA/LA (Latin American & Latino Art in Los Angeles), have been given as a starting point towards conversations about the sub-representation of minorities on the institutional-art setting at international level, and openness to a stronger confrontation from the artists on the implausible times and of constant dehumanization in which we currently live. The orientation of these curatorial efforts, beyond being a protest, is an eloquent way to reconsider a dialogue that had been forgotten. The political charge of A Decolonial Atlas is certainly undeniable and the fundamental part of the exhibition.

Comments

There are no coments available.